Cornell researcher who studied what we eat and why will step down after six studies are retracted

- Share via

A Cornell University professor whose attention-getting studies reported that guests at Super Bowl parties consumed more calories when served snacks from larger bowls and that couch potatoes ate nearly twice as much when watching an action-packed movie than when viewing a PBS talk show will step down from the university at the end of the academic year.

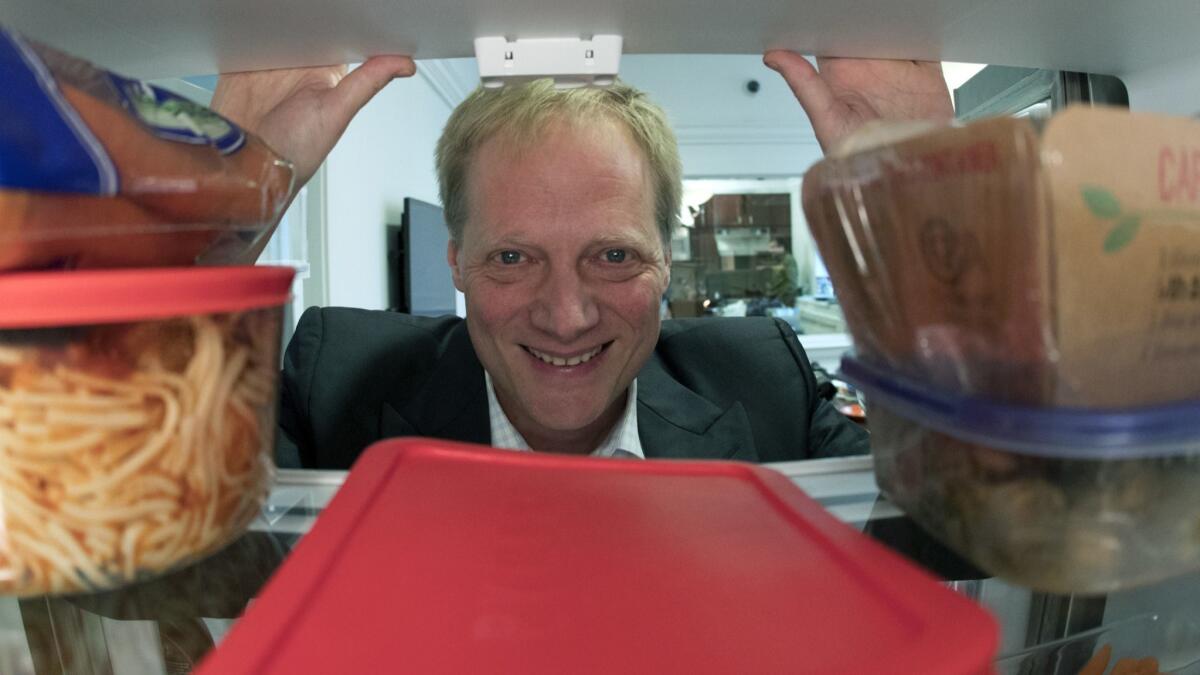

Brian Wansink, the longtime director of Cornell’s Food and Brand Lab, submitted his resignation this week after a year-long review concluded that he committed academic misconduct, according to a statement from the university’s provost.

Wansink’s offenses included “misreporting of research data, problematic statistical techniques, failure to properly document and preserve research results, and inappropriate authorship,” Provost Michael I. Kotlikoff said in the statement released Thursday.

It came on the same day that three prominent medical journals — the Journal of the American Medical Assn., JAMA Internal Medicine and JAMA Pediatrics — retracted six of his research studies after Cornell said it could not vouch for their legitimacy. The studies were published between 2005 and 2014.

“We regret that, because we do not have access to the original data, we cannot assure you that the results of these studies are valid,” Cornell told JAMA’s editors.

Kotlikoff said Wansink is no longer teaching or conducting research. “Instead, he will be obligated to spend his time cooperating with the university in its ongoing review of his prior research,” the provost said.

In a statement sent to the Washington Post, Wansink asserted that he and the school mutually decided to part ways because they have different approaches to research.

Wansink also told the Cornell Daily Sun that “there was no fraud, no intentional misreporting, no plagiarism, or no misappropriation” in his work.

He acknowledged that some of his studies included errors like incorrect descriptions of participants’ age groups, typos and “statistical mistakes.” In all but one case, these errors did not affect the study results, he told the student newspaper.

Wansink’s work combined aspects of food psychology, consumer behavior, nutrition and obesity research. The result was a steady stream of papers that were equally accessible to both academics and members of the general public.

For his 2005 report on serving bowl sizes, he invited 40 graduate students to attend a Super Bowl party and offered them roasted nuts and a pretzel-and-chips mix. According to the study, graduate students who scooped snacks from 4-liter bowls served themselves 142 more calories, on average, than those who served themselves from 2-liter bowls. Wansink’s conclusion was that the size of the serving bowl “may provide a consumption cue that implicitly suggests an appropriate amount to eat.”

In the 2014 TV study, 94 undergrads were offered M&Ms, cookies, carrots and grapes while they watched the Michael Bay thriller “The Island” or an episode of “Charlie Rose.” He reported that students who watched the movie consumed 98% more grams of food and 65% more calories over 20 minutes than their counterparts who watched the talk show. His conclusion: “The more distracting a TV show, the less attention people appear to pay to eating, and the more they eat.”

Other retracted studies reported that grocery shoppers who hadn’t eaten in five hours put more high-calorie foods in their carts compared to shoppers who had snacked on Wheat Thins; that preschoolers requested more Froot Loops when given a large cereal bowl instead of a small one; and that people who hadn’t eaten for 18 hours were more likely to start off their lunch with French fries or a roll than people who had eaten breakfast.

Altogether, Wansink’s studies were cited by other academics 26,743 times, his Google Scholar profile shows.

It all began to unravel in 2016, after Wansink wrote a blog post praising a visiting scholar in his lab for taking data from a “failed study” and turning it into five separate research papers.

In the post, Wansink described how the student kept analyzing the data until she found meaningful relationships. The pair wound up publishing studies with titles like “Low Prices and High Regret: How Pricing Influences Regret at All-You-Can-Eat Buffets” and “Eating Heavily: Men Eat More in the Company of Women.”

This did not sit well with other researchers, according to a report from BuzzFeed. The scientific method demands that researchers begin with a hypothesis, then generate data to see whether it holds up — not the other way around.

Critics compiled a “Wansink Dossier” of studies they saw as having problems ranging from “minor to very serious.” As of 2017, there were 52 studies on that list; 28 of them had been corrected or retracted.

Wansink told the Post that the latest spate of retractions came as “quite a surprise.”

“From what my coauthors and I believed, the independent analyses of our data sets confirmed all of our published findings,” he said. “What we did not keep over the past 25 years are the original pencil and paper surveys and coding sheets that were used in these papers. That is, once we combined all the data into spreadsheets, we tossed the pencil and paper versions. That might be why they said they couldn’t reproduce these from scratch (that is, there was no scratch).”

He added that he remains “very proud of all of these papers, and I’m confident they will be replicated by other groups.”

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE