Study of Britain produces first fine-scale genetic map of a nation

- Share via

Britain may be famous for preserving its royal DNA, but a genetic analysis of the nation is providing new insights into the “story of the masses,” according to scientists.

Researchers announced Wednesday that they had created the world’s first fine-scale genetic map of any country, an achievement that allowed them to settle a few long-running debates about the history and bloodlines of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The group’s most surprising finding was its failure to identify a single “Celtic” genetic group. In fact, the researchers said that the Celtic regions of Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Cornwall were among the most genetically different.

Likewise, they found no clear genetic evidence of the Danish Viking occupation and control of a large part of England during the 9th century, suggesting a “relatively limited input of DNA.”

The research, which was published Wednesday in the journal Nature, was conducted by an international team and led by scientists from the University of Oxford, University College London and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia.

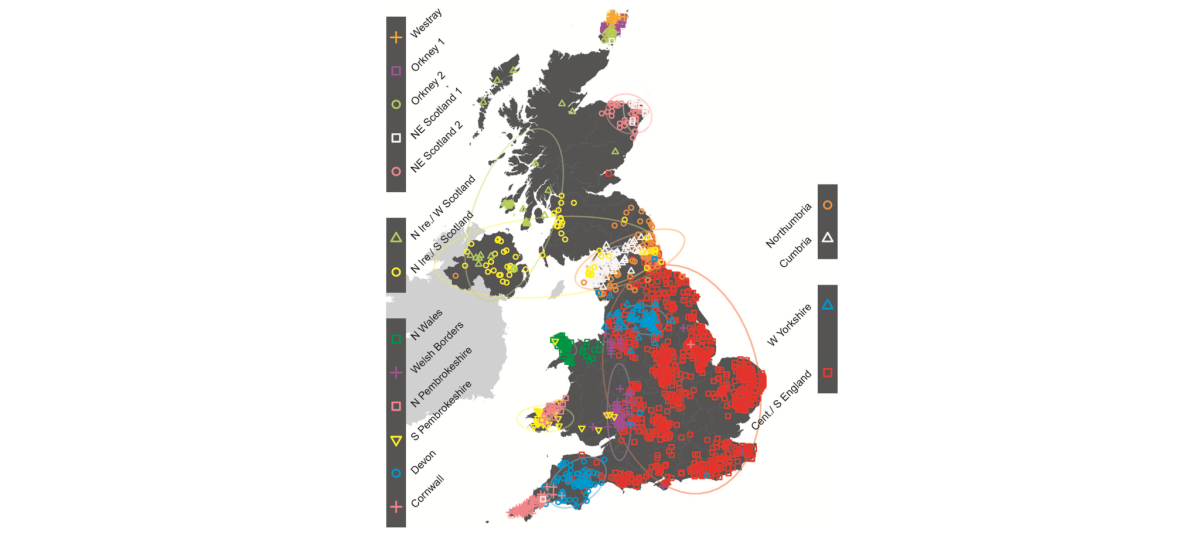

The People of the British Isles study was based on sophisticated statistical analysis of DNA samples from 2,030 rural British residents. Each of the white DNA donors had all four of their grandparents born within 48 miles of one another, essentially allowing researchers to sample the DNA of the grandparents in specific regions.

The DNA samples were studied for differences at roughly half a million positions along the genome, and were then grouped by similarity. Researchers plotted each DNA donor on a map, positioning the donors at the geographic midpoint of their grandparents’ birthplaces.

“What was striking was the pattern of variation we saw and the way it aligned with geography,” said coauthor Peter Donnelly, director of the Wellcome Trust Center for Human Genetics at the University of Oxford.

Subtle yet identifiable genetic patterns could be found separated by current-day county lines, Donnelly said. Such was the case with Cornwall and Devon, in England’s southwest.

In order to provide context, researchers also analyzed DNA samples from 6,209 volunteers from 10 other European nations. That data allowed researchers to determine the genetic contributions of people from other parts of Europe.

The researchers found noticeable contributions of DNA from the Anglo-Saxons, the Germanic tribes who migrated to eastern, central and southern England in the 5th century, after the departure of Roman forces.

“After the Saxon migrations, the language, place names, cereal crops and pottery styles all changed from that of the existing population to those of the Saxon migrants,” lead study author Stephen Leslie, a genetics statistician at the Murdoch institute, and his colleagues wrote.

“There has been ongoing historical and archaeological controversy about the extent to which the Saxons replaced the existing Romano-British populations,” the authors wrote. “With genome-wide data we can now resolve this debate.”

The answer, researchers said, was that Anglo-Saxons intermarried with, rather than replaced, the existing populations.

“We estimate the proportion of Saxon ancestry in central and southern England as very likely to be under 50%, and most likely in the range of 10% to 40%,” authors wrote.

The population in the northern Orkney Islands was also distinct, with 25% of DNA coming from Norwegian ancestors, the result of an 800-year-long Norse Viking occupation that began in the 9th century.

“That perhaps was not surprising,” Donnelly said.

The researchers also found that the Welsh appear more similar to the earliest settlers of Britain after the last ice age than all other groups, and that there was genetic evidence of the Landsker Line -- the boundary between English-speaking people in southwest Pembrokeshire and the Welsh speakers in the rest of Wales.

In addition to settling some debated points of history, the research may also help with medical research.

“Building a picture of population genetics at this scale may in the future help us design genetic studies to investigate disease,” said Dr. Michael Dunn, head of genetics and molecular sciences at the Wellcome Trust, which funded the research.

Follow @montemorin for science news