Upgrading from a cardboard box for the homeless

- Share via

Christopher Raynor’s father kicked him out when he was 13, after his stepmother interrupted an orgy in his bedroom and the teen jammed a broom handle against her throat.

Now 40, Raynor has lived much of his life in the rough. His current domicile is a patch of dirt behind some pampas grass and coastal sage scrub where Pacific Coast Highway meets Temescal Canyon Road, in the backyard of Pacific Palisades.

Until a few weeks ago, he dozed on a thin mattress in the open air. Now he beds down in a snug mobile shelter called an EDAR (short for Everyone Deserves a Roof), a covered contraption that looks like the offspring of a shopping cart and a pop-up camper.

Raynor’s mother died of stomach cancer, his father was shot to death, and he himself has served time in jail. He spends much of each day intoxicated and grimy. He despises most people.

But he likes his EDAR.

“This is one of the greatest damn gifts you could ever give to anybody,” he says.

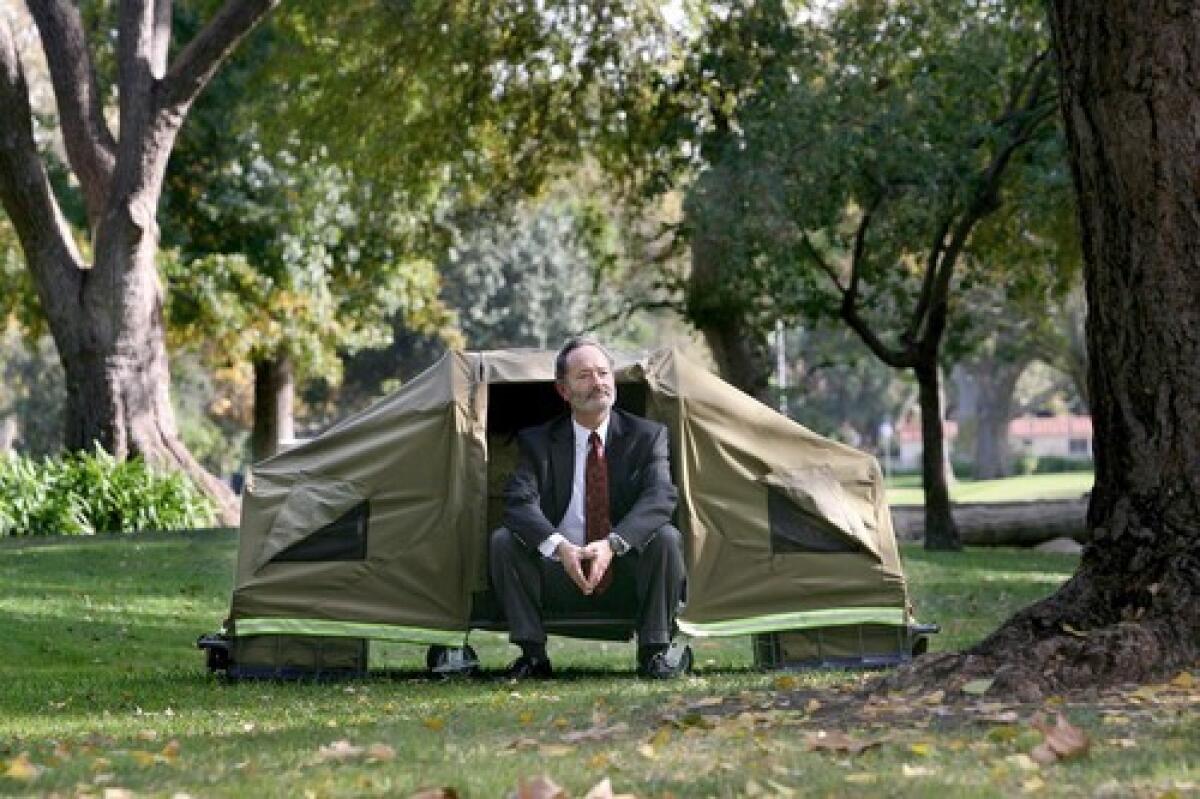

The EDAR is the brainchild of Peter Samuelson, a philanthropist and film producer whose credits include “Revenge of the Nerds” and “Arlington Road.” His life could hardly be more different from Raynor’s.

Samuelson grew up in a middle-class London household where performing charitable work was expected. His father, Sydney, founded Samuelson Film Service, a supplier of film and TV equipment, and in 1995 was knighted for his service to the British film industry.

Peter Samuelson went to Cambridge University on a full scholarship, earned a master’s degree in English literature and became fluent in French. He started in the film business as an interpreter for U.S. companies operating in Africa and Europe.

In 1975, after living off and on in Los Angeles, he settled here permanently, married an accountant and had four children.

“If you become an American on purpose, it’s a very special thing,” Samuelson, 57, said over breakfast at Nate’n Al deli in Beverly Hills. “America is not just a land of opportunity but also of personal responsibility. There’s an obligation to lift up society.”

In 1982, that obligation smacked Samuelson in the face when a cousin in London introduced him to a boy with an inoperable brain tumor. The child’s great wish was to see Disneyland. Samuelson and his cousin footed the bill to fly the boy and his mother to Los Angeles for a two-week whirlwind of wish fulfillment.

“He went back to London clutching his Mickey Mouse ears and died,” Samuelson said.

The experience prompted Samuelson to start the Starlight Foundation, an international charity that provides psychological and social services to seriously ill children and their families.

In 1990, he brought together director Steven Spielberg and Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, among others, to create the Starbright Foundation, which develops software and other products to help children cope with the medical, emotional and social challenges of their illnesses. In 2004, Starlight and Starbright merged to become the Starlight Starbright Children’s Foundation. Another Samuelson charity, First Star, advocates for abused and neglected children.

Three years ago, on his twice-weekly bike rides to the beach from his Holmby Hills house, Samuelson realized that he was seeing more homeless people. For three weeks, he interviewed dozens of them -- men, women and children.

“Where do you spend the night?” he asked one woman. She led him by the hand into the bushes and showed him a large cardboard Sub-Zero box.

“That was my epiphany moment,” Samuelson said. “I’ve got the refrigerator. She’s got the box. What is wrong with this picture?”

A 2007 homeless census revealed that on any given day there were more than 73,000 homeless people in Los Angeles County. (Some critics contend the number is overstated.) Downtown’s skid row had the greatest concentration, with more than 5,000.

Samuelson said he was shocked by the demographics: About 60% of the homeless were men, 24% were women, and 15% were under 18. (Adult transgender individuals accounted for the rest.)

“I’ve always believed society is defined by how we deal with our weakest links,” he said. “The best of America is when we take care of the less fortunate.”

His first instinct was to build shelters, but then he did the math. Building a bed in a facility runs $50,000 to $100,000. The cost to house all of the county’s street denizens would run into the billions. Besides, many of them resist services. So he thought: What is there that’s better than a damp box on a rainy night even if it’s not as good as a bed?

The idea of a mobile, single-person shelter popped to mind.

Samuelson sponsored a contest at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena to design his “widget.”

Eric Lindeman and Jason Zasa took the honors, with a mobile shopping cart-like apparatus. The cart features bins to hold cans, bottles and other recyclables collected by day. It folds out to create a sleeping platform, topped by a canvas cover with zippers and windows.

Samuelson labeled it an EDAR, and established the EDAR Foundation, whose slogan is: “Thinking outside the box.”

With a donation from former EBay President Jeff Skoll, he took the design to Precision Wire Products, a manufacturer of shopping carts in Commerce. Precision produced a succession of prototypes, at least nine, to address critiques of the device: too big, too small, too flimsy, not readily collapsible. The units have been thrown down flights of stairs (they’re sturdy) and left in the rain (they don’t leak).

Three months ago, Samuelson decided to distribute 60 EDARs for testing. With the help of churches, missions and shelters, he and his assistants identified chronically homeless people who could benefit from an EDAR in the short term and might be willing to develop a lasting relationship with service providers.

After Dehanka Straughter was laid off from her job as a cook at a Compton preschool, she and her two sons, ages 2 and 6, were evicted from their $975-a-month apartment.

They sold their furniture, stored some possessions in Straughter’s unregistered car and stayed with family and friends for a few weeks. When Straughter saw people sleeping on the streets, she thought “that’s where we’d be next.” Then a friend told her that women and children could find temporary quarters at the Union Rescue Mission in downtown Los Angeles.

Now the petite Straughter, 27, sleeps in an EDAR with her boys on the fourth floor of the mission. They like it better than she does. “The kids adjust to anything,” she said. “They think they’re camping.”

Still, she says, “I’m happy to have a place to bathe and eat and sleep.”

With the economy sinking, mission Chief Executive Andy Bales is making room for more mothers with children and hopes to provide EDARs -- indoors -- for many of them. The EDAR Foundation provided 17 units; the mission has asked to buy 100 more, some for use in its winter shelter.

Bales hopes that with mass production, the price will drop to $400 from just under $500.

“They make a nice cot and provide a lot of privacy,” he said. “I had a 6-foot-7 friend lie down in one. He was comfortable.”

Raynor learned about EDAR from homeless acquaintances. A high school dropout and former construction worker, Raynor had spent three years in jail for auto theft and forgery. With police after him in Texas and his home state of Missouri, he went to Arizona. He left there in search of more temperate weather and found it next to Pacific Coast Highway.

As traffic rushed by one recent starry Friday night, Raynor reminisced about his brushes with the law. Beer can in hand, he spoke of jumping a freight train to Texas to search for a friend’s missing 13-year-old daughter. Wielding a sawed-off shotgun, he banged down a door and tied up two men who he thought knew her whereabouts. “How was I to know they were cops working on a sting operation?” he said.

Recently, a woman he described as his fiancee was struck and killed by a driver on PCH. Not long after, a male friend suffered the same fate, he said. The woman he’d married in Arizona disappeared from his life. He shares his PCH-adjacent turf with a woman named Yolanda, whose speech has been slurred by alcohol and a head injury.

Raynor said his EDAR is “very comfortable,” cooled by sea breezes by day and made cozy by his body heat at night.

“It’s about time someone took an initiative for people less fortunate than themselves,” he said.

In October, the EDAR won $10,000 in an innovation contest sponsored by Los Angeles Social Venture Partners, the Social Enterprise Institute and the USC Stevens Institute for Innovation. The EDAR Foundation ( www.edar.org) is seeking donations to produce more of the mobile shelters.

Students at Rand Corp., the Santa Monica think tank, are interviewing EDAR users and representatives of shelters and missions to assess how the units might fit into a system of comprehensive care for the homeless.

“The goal is to find out who will benefit most from this unit and therefore what the distribution plan should look like,” said Barbara Raymond, a consultant working on the study. Raymond sees possibilities for EDARs in refugee camps and for victims of natural disasters.

Meanwhile, lawyers are sorting out legal issues. Will municipal codes allow users to park their units anywhere? What about constitutional questions and not-in-my-backyard complaints?

Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Irvine School of Law, said police fear the units could constitute dwellings where inhabitants would have a reasonable expectation of privacy. In that scenario, police would need warrants to search EDARs, which could become havens for drug use or prostitution. Chemerinsky maintains that cities could allow the units in designated public places as long as users consented to be searched, much like travelers entering an airport.

Samuelson anticipates those and other objections to his invention. Does the EDAR enable homelessness by making it more bearable? No, he insists.

“Why is the EDAR not regressive?” he said. “Because it is not nearly as good as a shelter bed. There’s no pretense it’s as good as permanent or temporary brick-and-mortar housing.” But it is, he says, “infinitely better than a damp cardboard box.”

Groves is a Times staff writer.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.