In Ensenada, Mexico, couple takes recycling to new highs

Reporting from Ensenada, Mexico — Most things in the lives of Alejandro D’Acosta and Claudia Turrent are recycled: the trailer in which the architects live, their 3-year-old Christmas tree, even their rescued dogs. “The only thing not reciclada is my wife,” D’Acosta says with a grin, his wedding-ring finger tattooed with her name.

“Ay, gordo! What am I going to do with you?” Turrent admonishes him, laughing, her right wrist imprinted with his name like a bracelet. The couple show their good humor, but make no mistake: They are on a serious quest to promote a sustainable way of life for themselves and their community in the nascent revolución verde just south of the Tijuana border.

The Ensenada coast and nearby Valle de Guadalupe wine-making region inland are testing grounds for the couple’s experiments in recycling and “upcycling,” the process of designing a product with its end-life in mind.

“Recycling is taking an object, like a plastic bottle, and after you drink it, turning it into a candleholder,” Turrent says. “We want companies designing the plastic bottle to design it in the shape of something functional, like a roof tile.” Instead of ending up in a landfill, she says, the plastic could be incorporated into an interlocking system of bottles that provide cover. “This would help many poor people have a shelter over their heads, and at the same time, the Earth will be cleaner.”

At the rear of the couple’s home facing the northern Baja coastline, where waves break dramatically along the shore, a brown Christmas tree stands in the small garden.

“The tree was a big discussion at Christmas,” D’Acosta says. “My children told me, ‘It smells like fish, and we want a new one that smells more like Christmas.’ I told them, ‘This tree will be for my grandchildren and great-grandchildren.’ ” The architect shakes his finger in the air to drill home his point of living lightly on the land.

Even the family’s adopted dogs are recycled -- well, sort of. In the nearby agricultural valley, the strays had recently killed a turkey, an offense that often means death for dogs as well. “They now have a second life, so they’re recycled too,” D’Acosta says, laughing.

Originally from Mexico City, the couple spent eight years living in Oaxaca building their own projects, teaching and aiding poor communities in the area by building health facilities and cultural centers. Along the way, they learned to create a modern architecture based on ancient traditions. A local bar, La Mezcaleria, features walls and a ceiling woven of carrizo, or cane grass, which the indigenous people also use for roofs, window coverings and baskets.

“Es una canasta” -- “it’s a basket” -- D’Acosta says of the structure. When the sun’s rays stream into the interior, Goethe’s description of architecture as frozen music comes to mind.

“We have much to learn from indigenous people and the way they live with the land,” D’Acosta says. “Some people call them backward, but they don’t need cars because they grow their food in the garden next to their house; they use the natural materials that surround them to make their homes.”

The couple have taken the lessons they learned in Oaxaca and created a vernacular architecture of their own based on materials that surround them in northern Baja. And the material found in most abundance here, they say, is basura -- trash.

::

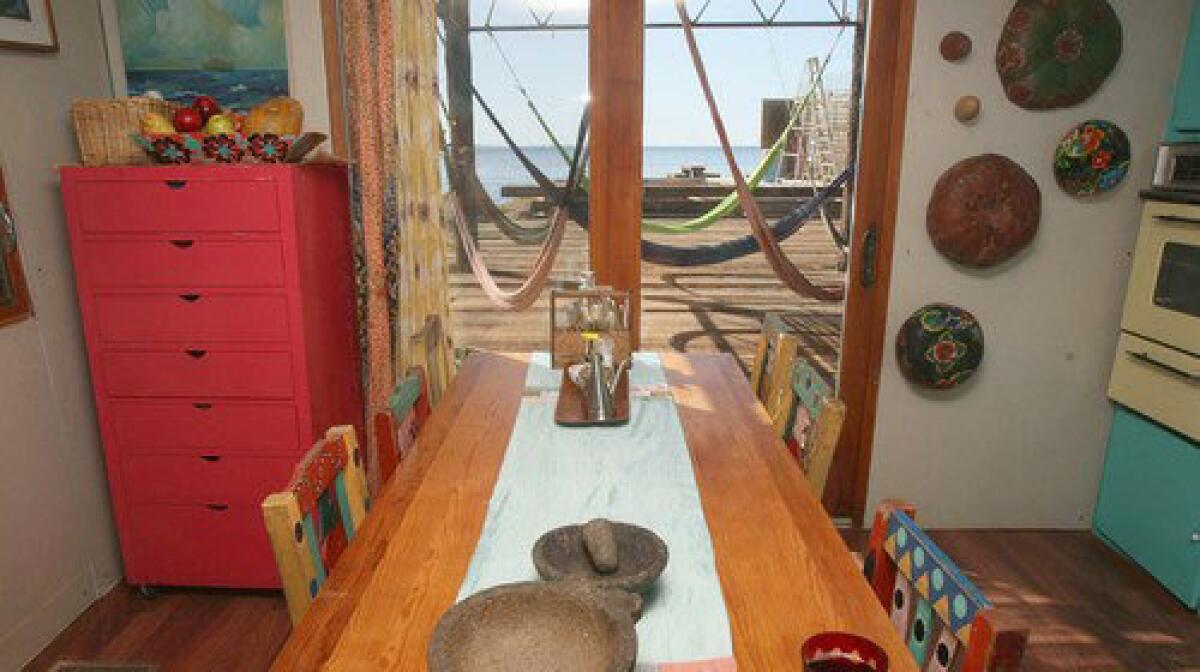

D’Acosta and Turrent’s home is a laboratory. They joined a 1940s American mobile home with a former Mexican office trailer to create a comfortable, inexpensive dwelling that seems to float on the land, parallel to the sea. The 60-foot-long red mobile home, re-clad in waterproof corrugated cardboard, houses the kitchen, living room, two girls’ bedrooms and a bath. The shorter trailer, set at a right angle, serves as the master bedroom suite overlooking the ocean.

The house wears an interior skin of unpainted dry wall and is filled with recycled furniture from Los Globos, an area of Ensenada with secondhand shops. Other recycled objects take on new lives in the house. A whale vertebrae is now a sculptural centerpiece atop the patio dining table. A vintage blouse is a cover for the plasma TV. A ‘70s desk serves as the kitchen table.

In the master bathroom, the glass wall is covered with X-rays of family and close friends. Backed by a green shower curtain, the film is illuminated by the afternoon sun and given a psychedelic glow.

“We see inside the people we love -- they are more naked than naked,” D’Acosta says, placing his face next to an X-ray of his own broken clavicle. “They are part of the house now.”

Outside, a long deck made of redwood beams from an old, deconstructed bridge stretches to the shore. An open-air aluminum-and-wood pavilion, reclaimed from an old factory, is covered with carrizo, echoing the trailer’s topping of palm fronds. The materials, salvaged from their neighbor’s trash heap, help to cool the spaces.

“Our neighbor used to throw things out; now he asks us before disposing of anything,” says D’Acosta, who can be found most Sundays combing the coastline for trash, often returning with a necklace of plastic bottles draped around his neck.

“Gifts from our northern neighbors,” he quips, referring to refuse that has washed down from California. “They make great insulation.”

In fact, he’s planning to use the colorful bottles in a new wine-tasting center at La Escuelita, a wine school started six years ago by his brother, Hugo D’Acosta, in the Valle de Guadalupe. Set in a former 1940s olive oil factory that still produces olive oil as well as wine, the school is where D’Acosta keeps stashes of trash in segregated piles.

“Another laboratorio,” he says, pointing to mounds of cans, tires, rusted pipes, barbed wire and old wood, as well as a lone toilet where he takes up a seat to gaze at his tesoro.

Treasure? Most people would look at all this and see junk.

D’Acosta, like Don Quixote on his quest, conjures other visions. Buildings on the property have been fashioned from the trash: a classroom made of colorful palos, discarded pieces of wood from construction sites; a wine storage facility composed of used bottles; and an open-air building framed in rusted box springs.

Then there’s the front of the school, clad in discarded filters used in the pressing of olive oil. Nearby, old irrigation hoses woven into a fence resemble a latticework of squiggly, charcoal snakes. At the rear of the property, another artful fence consists of dead grapevines.

::

His latest structure is a work in progress: a wine-tasting center made of old barrel staves. Colorful plastic bottles will be placed between walls as insulation and to “color the light,” he says. The barrels’ metal bands, laid in concentric circles, await cement to complete the floor. Old wine barrels, fittingly, will make up the wine bar.

“The idea of buildings is not just for function but to create sensations,” D’Acosta says.

“Each material has its own soul, and when you reuse that material it has a new soul on top of its old soul.”

Turrent has her own project, Viento, a high-rise condominium in El Sauzal, a seaside community just north of Ensenada, complete with an in-house wine-making facility that will be cooled by sea breezes and heated by the sun. Turrent and D’Acosta’s signature fence of palos marks the property. She’s experimenting with hand-carved furnishings -- built-in benches, wooden sink stands -- made from the same redwood beams that form her home’s deck.

While the project is on hold, Turrent has turned her attention to retrofitting a half-dozen trailers on the property as part of a new deli-market by the sea. The wine trailer features interior walls, flooring and ceiling of oriented strand board, or OSB. Holes cut into the board hold an array of wine bottles. Total cost: $1,500. Start-to-finish timeline: one month. “It’s cheap and fast -- and it’s recycled,” Turrent says.

Come summer, when wine aficionados hit Ensenada’s Fiesta de la Vendemía (Harvest Festival) and other cultural events, the new market will be in place offering organic and regional products -- again supporting the sustainable ethos.

“The idea,” she says, “is to bring small producers together and promote the idea of buying local.”

Inland, in the Valle de Guadalupe, lies D’Acosta’s latest boutique-winery, Paralelo. With its corrugated metal roof painted the color of nearby olive trees, the rammed-earth structure all but disappears into the landscape. Walls imprinted with olive branches, cactus, even truck tires offer traces of the nearby countryside. During harvest, trucks drive up the building’s eastern ramp to the roof, releasing grapes into the vats below.

“Everything is run by gravity,” D’Acosta says. No pumps are needed. Meter-wide walls, punctuated with barrel-shaped windows on each side of the building, regulate air flow to control temperature. “We try to work with the landscape, not against it,” says the architect, also a professor at the Autonomous University of Baja California, where his classes emphasize ecology and sustainability.

Baja conservation attorney José Luis Pérez Rocha recently worked with D’Acosta on transforming an abandoned 120-year-old school into a family home in La Paz, Mexico.

“Alejandro see things differently from the rest of us,” Rocha says. “He turns waste and trash into something not only useful but beautiful.”

Already copies of D’Acosta’s work -- fences of discarded lumber or recycled grapevines -- are popping up in the Valle de Guadalupe and Ensenada. But D’Acosta says that’s a good thing. “People are starting to look at trash as something that has value.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.