Chivas owner Jorge Vergara rides wave of popularity, criticism to success

GUADALAJARA — The first thing you notice about Jorge Vergara are his socks. He’s not wearing any.

“One day when I was 11 or 12, I thought, ‘Why do you wear socks?,’ ” he says. He couldn’t come up with a suitable answer, so he hasn’t worn them since.

That kind of logic hasn’t always played well in the button-down Mexican business world. But it’s not the only sector of Mexican society the iconoclastic Vergara is shaking up. In the seven years since he bought the financially troubled Chivas de Guadalajara soccer team, Vergara has been hailed and hated, loved and loathed -- often at the same time by the same people.

To understand why any of this matters outside Chivas’ home state of Jalisco, though, you have to know a little bit about Chivas, which is less a soccer team than it is a 103-year-old national institution.

The most popular sports franchise in Mexico, Chivas is the only soccer team in the elite first division that has never used a non-Mexican player. And its huge fan base extends north of the border, one reason why Chivas is playing a friendly on Saturday against FC Barcelona in San Francisco.

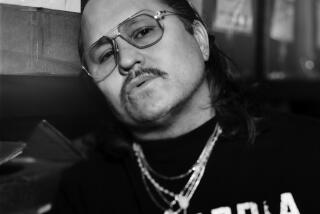

The face of the Chivas franchise is Vergara, a graying, bilingual, motorcycle-riding 54-year-old who made his millions peddling nutritional supplements and whose passion, critics say, clouds his judgment. But critics can’t question the team’s success under Vergara, including winning a record 11th national championship, becoming profitable again, and in December his team will move into a modern 45,500-seat artificial-turf stadium shaped like a volcano with a cloud on top. Last week Chivas opened play in the second of the Mexican first division’s two annual seasons, heavily favored to win another title.

If all that makes Vergara sound a little like the Dallas Cowboys’ Jerry Jones or the New York Yankees’ George Steinbrenner, you’re not the first to reach that conclusion.

Still, like Jones and Steinbrenner, Vergara is as controversial as his team has been successful. Consider:

* After Chivas opened the current season with a pair of losses, Vergara turned to his Twitter account to rip the team.

“I’m frustrated and we can’t keep on going like this,” he wrote. “I can’t say what we’re going to do, but we need to find a solution immediately.”

* Chivas has had nine coaches in seven years under Vergara, including three in a 17-day stretch this spring.

* During negotiations for a new broadcast deal a few years back, Vergara kept his team off TV for two weeks until Mexican TV giant Televisa paid an unprecedented $200 million for Mexican soccer rights, but not before alienating some fans.

* He frequently meddles in coaching decisions, including demoting popular striker Carlos Ochoa to Chivas’ top developmental team last spring, when the team missed the playoffs. (Ochoa has since joined another club.)

Despite it all, Chivas’ popularity is at an all-time high. Vergara likes to recount a story from a few seasons back when a fan waited until after his marriage to tell his newlywed wife that he’d canceled their honeymoon and instead booked a trip to Guadalajara for a Chivas game. “It’s the team that everyone is watching,” says Ochoa.

Juan Serrates, a Jalisco native and longtime Chivas fan now living in Hawthorne, added: “You love [Vergara] sometimes, other times you’re looking at him and you’re thinking, ‘What are you doing?’ But there’s something to his madness.”

Even critics agree that Vergara saved the money-losing franchise, buying Chivas when fans feared it was about to be sold to backers of the team’s hated rival, Club America of Mexico City.

“It was being destroyed,” Vergara recalled. “They were buying and selling players [with] the archrival, which I haven’t done and which I will never do. The tradition was going away.”

The tradition Chivas fans care most about has kept the team from using non-Mexican players -- although the definition of who is and isn’t Mexican has blurred in recent years.

For example, when forward Jesus Padilla made his Chivas debut three years ago the team’s website said he was born in Jalisco. It still does, even though Padilla, 22, and the team now concede he was born and raised in San Jose, Calif., and didn’t move to Mexico until he was in high school.

“We go by the definition in the Constitution,” Vergara says. “Mexican law says that you are a Mexican if you are born outside Mexico and both parents are Mexican.”

Protecting its reputation as a Mexican-only team is vital for Chivas, because many fans identify with its Mexicanisimo more than anything else. Vergara even had the team’s bylaws amended to assure Chivas never plays a non-Mexican.

The son of a Guadalajara executive, Vergara is an unlikely defender of tradition. He skipped college and worked as an office runner, mechanic, translator and a maitre d’ before discovering his talent for sales. After his wholesale food business failed, Vergara was, in his words, “fat, sick and broke” when he met the late Mark Hughes, founder of the Herbalife brand of dietary supplements, who encouraged Vergara to sell his products in Mexico.

Vergara found flaws with Hughes’ business model in Mexico, so in 1991 he borrowed $10,000 and created his own company, Omnilife. His company, which sells products through an army of independent vendors, grew into one of Latin America’s largest sellers of nutritional products, with reported sales of more than $1.2 billion by 2005. Vergara’s business empire now spans more than 36 firms in 14 countries, including insurance, banking, music and films -- his company financed the 2001 movie “Y Tu Mama Tambien” -- plus soccer teams, including his stake in Major League Soccer’s Chivas USA.

Resurrecting Chivas presented a different challenge. Although it had a long, proud tradition, Chivas was foundering when Vergara paid $120 million to buy the franchise in October 2002.

To boost revenue, the team’s storied striped jerseys now carry large and lucrative sponsorship logos advertising Toyota and a Mexican bakery, instead of a collection of smaller decals which had made the players look more like NASCAR drivers than soccer players. Vergara also struck valuable TV deals, including a five-year pact with Telemundo for U.S. broadcast rights to Chivas games.

“Financially, [Chivas] is in black numbers since last year,” Vergara says. “It has to be strong financially to be strong sport-wise.”

Vergara has invested money back into the team, spending $6 million annually on Chivas’ five developmental teams and building a school adjacent to the team’s training center. Many Chivas players, from developmental squads on up, finish their studies at his expense. “You can play soccer, you can finish your education,” says Padilla, who joined Chivas as a 14-year-old.

But if Vergara claims credit for making Chivas a success financially, success on the field hasn’t always kept pace -- and fans are quick to blame him.

His club hasn’t made it past the second round of the playoffs since 2006, and Chivas missed the playoffs last spring.

So when Vergara fired Chivas’ head coach five days before its game against America last spring, an opinion poll roundly condemned the move. One fan wrote: “Nothing Jorge Vergara does surprises me anymore.”

Despite that, the Chivas-America game drew a standing-room-only crowd of more than 60,000 in Guadalajara. And after Chivas’s 1-0 win, celebrating fans poured out of bars and restaurants all over the city, forcing street closures.

“Chivas fans are born with a Chivas flag in their crib,” Lorelia Marin, wearing a team jersey, said as she stood outside the stadium last spring. “People from [Guadalajara] are very passionate about what they like.”

Across the crowded parking lot Luis Alberto Guzman, a Chivas fan for decades, offered another reason why the franchise has endured.

“Chivas,” he said, “is like family.”

A dysfunctional family, perhaps. But a family nonetheless.

--