Skeptics hope Ohio State domestic violence situation ends with righteous equation

- Share via

The formula popped up during a recent news conference as Urban Meyer struggled to address the criticism and uncertainty swirling around him.

The Ohio State football coach was trying to explain what he knew — and when he knew — about a history of domestic violence allegations against a former staff member.

“E+R=O,” he said.

Meyer was referring to a popular concept in which “E” stands for the events we encounter in life, “R” stands for our response and “O” is the outcome. The point is, we can’t always control what happens to us, but we can choose our reaction.

“It’s something our team lives by,” the coach said. “You press pause and get your mind right … then you step up and do the right thing.”

All of which rings ironic with Meyer placed on administrative leave while the university investigates why he kept receivers coach Zach Smith on his staff for so long.

Meyer initially claimed he did not know until recently the extent of accusations against Smith, which date back to 2009. That turned out to be a lie.

“I deeply regret if I have failed in my words,” Meyer stated in a subsequent apology.

Now comes the important part: How will Ohio State respond?

The university is expected to issue a report soon. Given college football’s history with domestic violence and sexual assault — and its repeated failings with the “R” in Meyer’s formula — expectations remain guarded, at best.

“We’ve seen so many mishandlings, so many coverups,” said Brenda Tracy, a rape survivor turned activist. “It’s almost like you can’t put anything past them.”

::

It was less than two weeks ago that Ohio State administrators promised they would get to the truth “as expeditiously as possible.”

But the situation is confusing; not all the facts are public. This much is known:

In 2009, when Meyer was coaching at Florida, he became aware of an incident between Smith — who was an intern with the Gators — and Smith’s then-wife, Courtney. Meyer said he spoke to the couple but took no further action.

“It came back to me that what was reported wasn’t actually what happened,” he later said.

At least one more allegation surfaced in 2015, after Meyer had jumped to Ohio State and brought Smith with him. No charges were filed and the incident did not receive public attention.

But late last month, an Ohio judge granted a protective order on behalf of Courtney Smith, at which point the story made its way into the spotlight, thanks mainly to an article by college football reporter Brett McMurphy.

At that point, Meyer fired Zach Smith.

The coach then denied knowing about the 2015 allegation when speaking with reporters at the Big Ten Conference media days. Smith told a different story.

The former assistant said he conferred with his boss and athletic director Gene Smith at the time. He expressed confusion at Meyer pleading ignorance three years later.

“I don’t know what he was thinking. Not really,” Smith told ESPN. “He knows everything that has gone on in my marriage that he needed to know.”

Meyer’s denial — if not his reasons for keeping Smith on staff — ring familiar.

At Penn State, administrators and fellow coaches insisted they never knew about defensive coordinator Jerry Sandusky sexually abusing young boys — sometimes on school property — for more than a decade.

Adminstrators ultimately acknowledged a coverup, and the late Joe Paterno was fired as coach, his legacy tarnished. The school received a $60-million fine, scholarship reductions and a postseason ban.

“No price the NCAA can levy will repair the grievous damage inflicted by Jerry Sandusky on his victims,” NCAA President Mark Emmert said. “However, we can make clear that the culture, actions and inactions that allowed them to be victimized will not be tolerated in collegiate athletics.”

The scandal reinforced a perception that college football adheres to a win-at-all-cost mentality, perpetuated by overpaid, autocratic coaches and entitled young athletes.

A limited study of Division I schools in the mid-1990s had already found that male athletes made up 3% of the male student population, yet accounted for 19% of sexual assault allegations and 37% of domestic violence allegations.

When female kicker Katie Hnida accused a Colorado teammate of raping her in 2000, coach Gary Barnett said: “Katie was not only a girl, she was terrible.”

More recently, Baylor paid former coach Art Briles a reported $15-million severance in the wake of a scandal that saw the athletic department failing to address multiple complaints of rape and sexual assault by football players.

“I do think there’s a heightened sense of awareness now, but we have to change this god-like complex among coaches,” said Dave Ridpath, an Ohio University professor and member of the watchdog Drake Group. “People would rather win than much else. That changes people’s moral compass.”

Consider the relationship between coach Jimbo Fisher and his former star quarterback.

While they were together at Florida State, Jameis Winston had several brushes with the law, including a sexual assault allegation. No charges were filed in the latter instance, but prosecutors questioned the local police investigation and the school ultimately paid a $950,000 settlement to the accuser.

Fisher, who has consistently and often vehemently defended Winston, recently said: “I still think he’s a tremendous young man. I really do.”

Winston will serve a three-game NFL suspension this fall after a separate allegation that he groped an Uber driver. Meanwhile, Fisher has parlayed their on-field success at Florida State into a new job.

Texas A&M lured the coach away from Tallahassee this winter, offering him a $75-million contract.

::

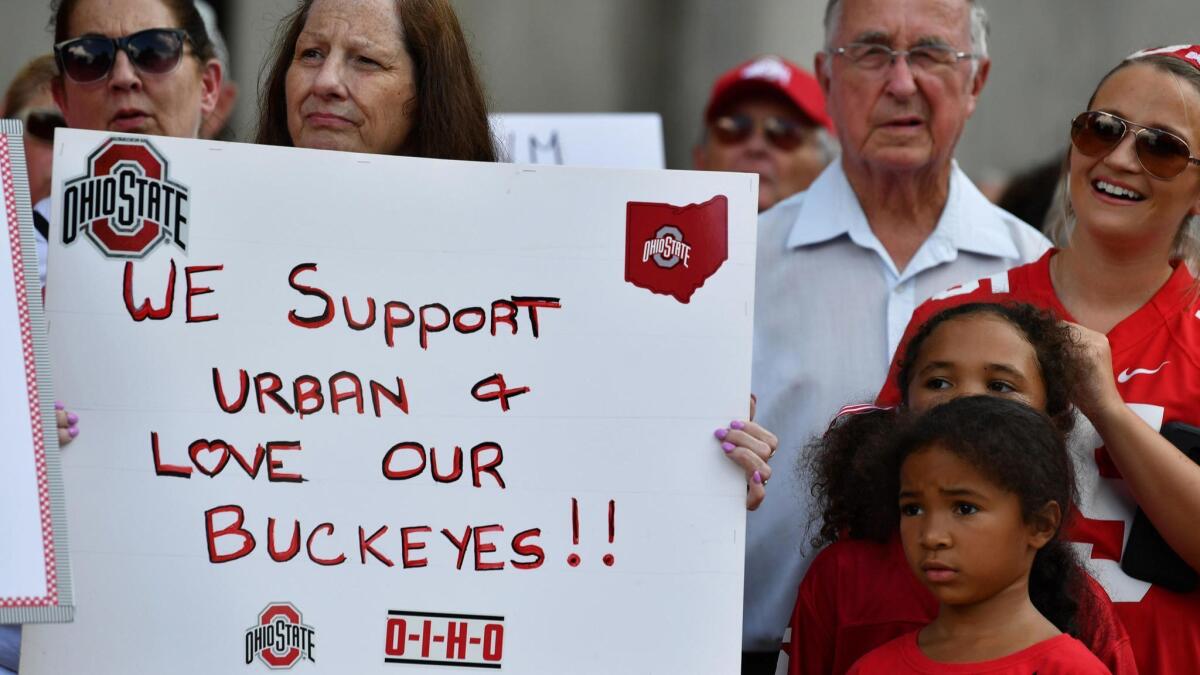

An estimated 200 Ohio State fans gathered on campus this week for an evening rally, carrying signs that read “Free Urban” and “Me Too! I support Urban Meyer.”

The next day, Courtney Smith’s lawyer issued a statement addressing what she characterized as “the misinformation that has been circulating” about her client.

Courtney had never been paid for an interview, had never been charged with a criminal offense and had made “concerted efforts” to press charges of domestic abuse against her ex-husband, attorney Julia Leveridge said.

Zach Smith has denied abusing his ex-wife but has acknowledged their relationship was “volatile” and “toxic.”

For Ohio State, the more-pressing question is whether Meyer and the athletic department acted wrongly in continuing to employ Smith. Not only did the coach and his assistant work together for more than a decade, but Zach is the grandson of Meyer’s longtime mentor, former coach Earle Bruce.

Meyer said he followed university protocol in reporting the allegations to his superiors and has fought suggestions he is indifferent to domestic violence.

“Please know that the truth is the ultimate power,” he stated. “And I am confident that I took appropriate action.”

All of this sounds familiar to Tracy, who became an activist after being raped in 1988 by four men, including two Oregon State football players. She has crisscrossed the nation speaking to college and high school teams.

The mother of two still sees evidence of long-standing problems in the game. Violent players are shuffled from high school to college to the pros. Coaches and athletic departments circle the wagons to protect their teams.

But, in this #MeToo era, she also sees glimmers of hope.

“I meet a lot of young men and administrators who are good people and want to do the right thing,” she said. “It might be slow, but any progress is important.”

Which is why Tracy is keeping an eye on what happens in Columbus, eager to see the university’s response.

It all goes back to the equation Meyer preaches to his players.

“Institutions have always cared more about money and their brand,” she said. “Is this school going to step up and do the right thing?”

Follow @LAtimesWharton on Twitter

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.