- Share via

The guy at the front desk hands Kendall Coyne Schofield a key on a string. She gathers an armful of hockey sticks and slings a heavy bag over her shoulder.

Things might be easier if she were a professional golfer or a point guard in the WNBA. There would be no reason to drive to this ice rink in Irvine at dinnertime, no need to lug all her stuff — equipment rattling inside that bag — through crowds of children who have come for skating lessons.

Finding her way down a dimly lighted hallway, Coyne Schofield unlocks the door to an auxiliary dressing room and changes alone. Her jersey is clean and white; a pink band holds her hair in a ponytail. Out on the ice, she joins a group of players who have invited her to their weeknight practice.

Soon her skates click rapid-fire, her arms pumping as she collects a loose puck and wheels toward the blue line. Pure speed makes her one of the top female players in the world, but, on this evening, the 27-year-old is working out with teenage boys.

“I’m a two-time Olympic medalist, but every day, I’m looking for a chance to practice,” she says. “Where is there open ice time? Can I jump in with a junior team?”

Nearly 50 years after Congress passed Title IX, female athletes are still scrambling for a fair shot in the male-dominated world of sport.

Not all high schools and universities meet the groundbreaking legislation’s benchmarks. At a higher level, the champion U.S. women’s soccer team has filed a $67-million gender discrimination lawsuit against its federation, and there are numerous sports where women cannot be true professionals.

In hockey, top Americans like Coyne Schofield and Canadians train with their national teams part-time; the rest of the year, they have only a small pro league that offers limited practices, weekend games and small salaries.

“It’s tough,” American star Hilary Knight says. “You’re playing in a glorified beer league.”

This winter, more than 200 players have taken matters into their own hands, skipping the pro season to embark on a barnstorming tour. With exhibition games across the continent, they hope to stir fan support and persuade the NHL to create an affiliate league, like the WNBA.

“We want to show everyone that we’re here,” Canadian player Sarah Nurse says. “We have this great game.”

There is no guarantee their gambit will succeed. But, like the others, Coyne Schofield is willing to take the gamble, even if it means spending her Tuesday night at a suburban rink with the Jr. Ducks under-16 squad.

“There are moments when you lose hope,” she says. “Is it worth it?”

::

No one disputes that, as part of the Education Amendments of 1972, which sought to prohibit discrimination based on sex, Title IX has opened the door for high school girls and college women to compete in far greater numbers.

That might explain why the first few generations after the law’s enactment hesitated to demand more. There were some rebels, such as tennis star Billie Jean King, but people who study Title IX say many female athletes were grateful for whatever gains they could get.

Now, with women still facing barriers, expectations have shifted.

“This is a generation of young women who grew up in a cultural context where girl empowerment is a central part of the popular discourse,” says Cheryl Cooky, an associate professor at Purdue University who has written extensively about gender and sports. “They are no longer satisfied with just a place on the team.”

Game Changers: Trailblazers

The Times’ profile series of women who are pioneers in sports.

As U.S. hockey player Jocelyne Lamoureux-Davidson puts it: “The time for being grateful has passed.”

When the women’s soccer team made headlines last spring with that gender discrimination lawsuit, filed just before the World Cup, it resonated with hockey players who had mounted a similar effort in 2017, threatening to boycott the world championships.

USA Hockey stood firm at first, vowing to field a replacement squad, even if it meant using rec league players.

“It was nerve-racking,” Knight recalls.

Public sentiment eventually swung in the team’s favor as 20 U.S. Senators wrote a letter of support. The federation capitulated, boosting salaries to about $70,000 and improving practice conditions and providing more support for youth development. But the pay concessions applied to only the 20 or so women on the national roster.

“What we have,” Coyne Schofield says, “it’s not good enough.”

::

Her parents put her in figure-skating class when she was young, but that lasted only a week or so. Coyne Schofield saw her older brother playing hockey and declared: “I want to do what he does.”

Learning to stickhandle and shoot would not be the only challenges.

Girls in her hometown outside Chicago tended to sign up for sports such as softball or volleyball, so she had to join a boys team. Schoolmates teased her, called her a tomboy, told her to act normal; she thought about quitting but did not.

The streaming video revolution that is upending the long-entrenched habits of TV viewers is creating more opportunities for women’s sports to get wider exposure.

“Every time I went to the rink,” she says, “I realized this was my true love.”

It helped when her parents enrolled her in a hockey camp with other girls who harbored the same passion. Cammi Granato made an appearance, fresh from leading the U.S. women to victory at the 1998 Winter Olympics.

“I got to hold her gold medal,” Coyne Schofield recalls.

At the time, female players had a shot at a college scholarship and a chance to play in the Olympics. That was enough to keep Coyne Schofield practicing, honing a game marked by bursts of acceleration and a knack for finding the net.

Playing for the national junior team and then Northeastern University in Boston, she forged a reputation as a scorer and was called up to the U.S. senior roster while still in college. The 5-foot-2 forward responded with two goals and four assists as the Americans took silver at the 2014 Winter Olympics.

The pros weren’t much of an option. Coyne Schofield knew this; she was on her way to earning a communications degree with thoughts of a career beyond sports. But maybe, somewhere inside, hope lingered.

When veteran teammates on the national roster grumbled about the “post-grad” life, she recalls: “I thought they were just old and grumpy.”

::

The best female hockey players in North America had two choices for playing professionally, as of the 2018-19 season.

The Canadian Women’s Hockey League consisted of six teams and the National Women’s Hockey League, in the U.S., had five. Coyne Schofield played for the Minnesota Whitecaps of the NWHL.

Game Changers: NextGen

The Times’ profile series of women in sports who continue the fight for equality.

A pro salary of $7,000 did not warrant living apart from her husband — Michael Schofield is an offensive lineman for the Chargers — so she flew into St. Paul for weekend games, sleeping on a blow-up mattress in a teammate’s apartment.

“You’re not making much. Everyone is working 9-to-5 jobs,” she says. “It’s a grind and it sucks some of the love out of the game.”

Money is only part of the problem. Coyne Schofield sees her husband get daily practices, strength training and physical therapy at the Chargers facility and cannot help feeling exasperated.

“I know what it takes to be a professional athlete,” she says. “I can see it in my mind, but I just didn’t have the resources.”

The situation deteriorated further after last season as players traveled with their respective national teams to the world championships in Finland. Shortly before the tournament, the Canadian league folded.

“We were supposed to be focused on performing for our countries,” Canada’s Nurse recalls. “But we were also thinking, what does life look like when we get home?”

As everyone drifted down to the hotel lobby, a sense of shock morphed into something different. A plan was hatched.

You’ve seen them compete, these living breathing embodiments of strength and skill and athleticism. They’re women in sports, some of them trail blazers; others, members of a new generation of athletes.

NWHL players vowed to stand beside their CWHL counterparts; upon returning from the championships, everyone began making phone calls. Even some Europeans who played in North America joined in.

“Honestly, it was one conversation after another,” Coyne Schofield says. “We were all discussing how to make this work.”

They formed a union called the Professional Women’s Hockey Players Assn. and decided on a series of exhibition games. Billie Jean King offered advice, telling them: Stick together.

No one would get paid, but staging the tour would require financial backing. A major athletic shoe company chipped in. So did a chain of Canadian doughnut shops.

The whole thing came together in a matter of weeks.

The Dream Gap Tour started in September, at small, suburban rinks, drawing crowds of various sizes in cities such as Toronto and Chicago. Coyne Schofield led a women’s squad against former NHL players as part of a San Jose Sharks fan day.

The alumni game wasn’t exactly high-level competition, not with some of the older men huffing and puffing after the first few minutes. Coyne Schofield passed to teammate Gigi Marvin for an early assist, then snapped a shot into the corner of the net for a later goal.

No matter the circumstances, PWHPA players need to put on a show every time they take the ice. Coyne Schofield says: “I know we all feel the pressure.”

There is a crucial difference with women’s hockey — unlike the men, they are not allowed to body check. Some fans think less physical contact equals less excitement; others believe it encourages speed and skill.

This difference of opinion taps into a larger debate. In a free market, some argue, female athletes get the attention and salaries they deserve. If their professional leagues struggle, it means the product isn’t entertaining enough.

But proponents of women’s sport suggest a more-nuanced view. They see fewer resources devoted to youth development, less funding in colleges and less media coverage at the pro level. Nicole LaVoi, who heads the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport, recalls the NBA struggled in its early years: “They were given resources and they grew a fan base and created a market.”

We live in a country where sports remains our No. 1 metaphor. A national short-hand from which, until recently, most girls and women have been excluded.

At Purdue, Cooky points to a society that does not fully value women on the field of play.

“Title IX goes only so far,” she says. “It doesn’t change hearts and minds. It doesn’t change the historical trajectory of sport in American culture, which has always been centered on men.”

There are exceptions. Women have commanded the spotlight during soccer’s World Cup and at the Olympics, especially in sports such as gymnastics and figure skating.

When the U.S. hockey team defeated rival Canada in an overtime shootout at the 2018 Winter Games, the telecast drew about 3 million viewers, becoming the most-watched late-night broadcast on NBC Sports Network.

“We really felt like we created some buzz,” says Lamoureux-Davidson, who scored the winning goal for the Americans. “We proved there is value to our game.”

But that viral moment could not prevent a stalemate back home.

As the NWHL playoffs begin this week without many big names, the league has increased salaries by an unspecified amount, while offering players a share of sponsor-related revenue. Executives believe in a strategy of working deliberately, creating a brand city-by-city.

“We have to earn it, we have to fight for it, and we have to build that,” Commissioner Dani Rylan says. “It’s sad that some people look to the NHL or NHL teams to be the only solution to make women’s sports viable.”

The upstart PWHPA, meanwhile, has gained momentum with help from the NHL, which added a three-on-three women’s game to its All-Star weekend in January and has sponsored recent tour events in Philadelphia and Tempe. But no one is talking about creating a new women’s league, at least not yet.

The Times asked a sample of players, coaches and administrators to discuss the pressing issues of the day.

“What we’ve repeatedly said is, if there turns out to be a void — and we don’t wish that on anybody — then we’ll look at the possibilities and we’ll study what might be appropriate,” NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman told the Associated Press.

The “Dream Gap” players stop short of saying they want to kill the NWHL. Instead, they talk about the advantages of being connected to a larger, established men’s league.

WNBA players recently negotiated a landmark collective bargaining agreement that could boost average compensation to about $130,000 a year. It also guarantees maternity leave, a child care stipend, and reimbursement for family-planning expenses such as adoption and surrogacy.

Last spring, Coyne Schofield watched the WNBA draft on television.

“That was the coolest thing,” she says. “It’s the model we need to look at.”

::

The Jr. Ducks locker room is bright and noisy, bustling with teenagers who chatter as they pull on gear. When asked about Coyne Schofield, dressing alone down the hall, they grin.

“She’s really good,” Blake Mendez says.

Her talent and experience, not to mention the big “USA” emblazoned on her white national team jersey, make the younger players wonder why, exactly, she is practicing with them.

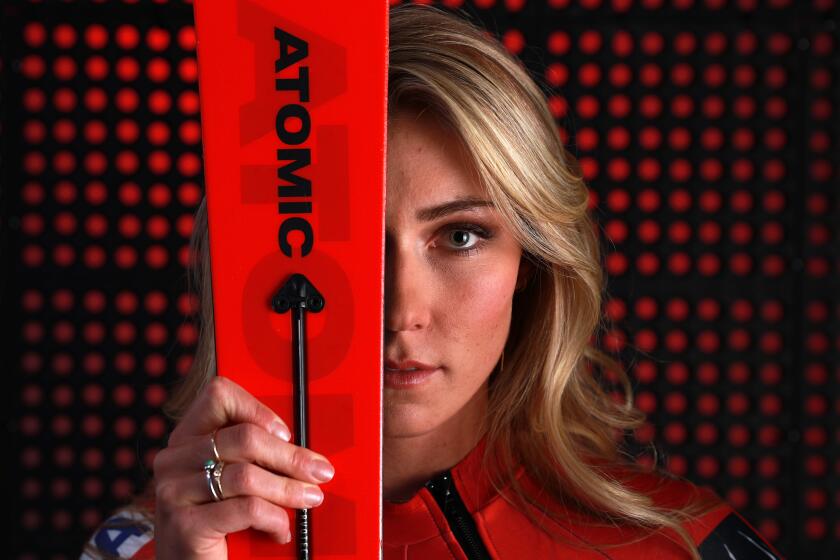

This is an elite-level athlete who has multiple world championships to go with her Olympic medals. Last winter, she became the first woman invited to compete at the NHL All-Star weekend, where she raced against men — beating one of them — in a fastest skater contest. Having worked as a television analyst, she will join the San Jose Sharks broadcast team for select games this season.

Yet, for all her credentials, Coyne Schofield struggled to find ice time when she and her husband arrived in Southern California for the Chargers’ season. She mistakenly called a roller-skating rink before contacting the Jr. Ducks.

“It’s not the same as the pros,” she says. “But I’m lucky they let me skate with them.”

The team has an hour to train before it must surrender the ice to another youth squad. Coyne Schofield turns quiet just beforehand, antsy to get started and get as much work as possible.

This sense of grit translates into passes that find their mark with pinpoint accuracy and tenacious hustle in each drill. Later, during a scrimmage, she slips through a crowd, searching for open space, and smacks into a larger boy, landing on her butt.

The Olympic star jumps up and smiles, patting him on the shoulder, before quickly skating off. There are only a few minutes left in practice.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.