A closer look at the ancient fine print

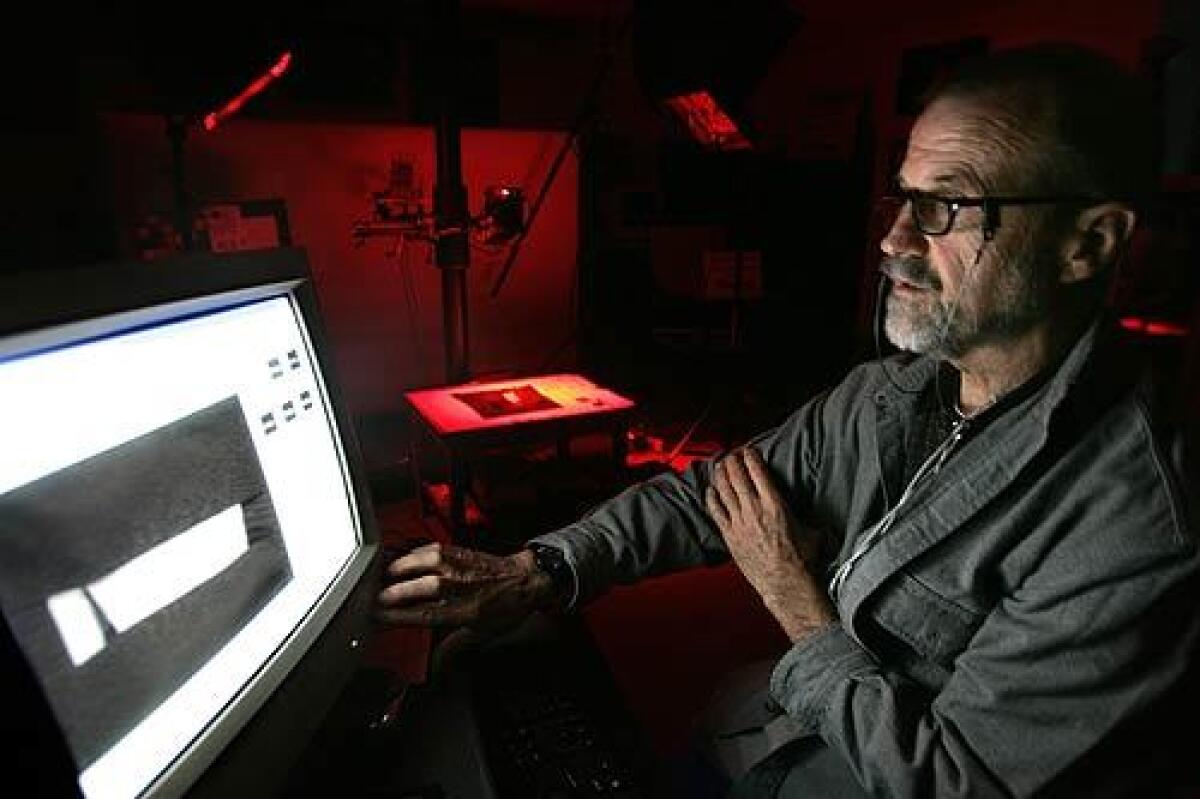

Researchers gathered recently in a small darkened lab near Santa Barbara, nervously pacing as a digital camera snapped hundreds of images of a shard of pottery resting a few feet below the lens.

There was good reason for their anxiety. The terra-cotta fragment is about 3,000 years old and was inscribed with five lines of text that could alter knowledge about the existence of an ancient Judean kingdom.

“To find any text is really off the charts,” said David Willner, an expert in Jewish antiquities who accompanied the shard from its excavation site in Israel to California. “And to have five lines of text is extraordinary.”

That this world treasure ended up at Megavision -- a small, employee-owned company tucked away in a nondescript industrial park -- speaks volumes about the firm’s growing reputation for the kind of specialized digital imaging sought by museums, archives, research institutes and elite collectors.

In the last year, Megavision Chief Executive Ken Boydston traveled to Washington, D.C., to help create a copy of the Waldseemueller map, the oldest-known map naming the American continent. At Oxford University, Boydston helped curators install an imaging system so academicians can more fully scrutinize ancient Egyptian documents.

Two weeks ago, Boydston got a call from Greg Bearman, a Pasadena scientist who has done extensive imaging work on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Archaeologists had unearthed a 5-inch-by-5-inch shard of pottery near the Valley of Elah -- site of the biblical battle between David and Goliath.

Bearman had been asked to create detailed images of the fragment to help researchers decode its message. But he didn’t have the necessary equipment. He asked Boydston: Could Megavision help?

After a flurry of soldering, drilling and snipping, Boydston’s team was ready when Bearman and a phalanx of researchers, archaeologists and technicians descended on Megavision’s tiny lab.

The result is hundreds of high-resolution images shot with different light filters. Using a process called spectral imaging, Boydston and Bill Christens-Barry, another imaging expert, aimed to maximize the contrast of the ink, made of charcoal and animal fat, against the terra-cotta piece.

Although they didn’t find any hidden text, the images will be sent back to Israel. Other high-tech images were produced -- using slightly different imaging techniques -- at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and two other technical shops on the East Cost.

Once the shard’s message is fully scrutinized and decoded, findings will be published in scholarly journals by Yosef Garfinkel of Hebrew University, who led the dig. A few words already deciphered -- “slave,” “king,” “land” and “judge” -- indicate that it may be a legal text, lending weight to some scholars’ belief that King David wielded considerable power over the Israelites.

Ancient scribes often wrote on broken bits of pottery because the material was plentiful and cheap, Bearman said. Papyrus and parchment were rare, he said.

Oxford University used carbon dating to determine that the text was written in the 10th century, 1,000 years earlier than the Dead Sea Scrolls, making it the oldest Hebrew text ever found.

“It’s an exciting thing,” Boydston said of the shard project. “It’s almost like passing on genetic codes for our cultural heritage.”

Megavision’s turn toward elite digital archiving comes more than two decades after it was founded in 1983 by Boydston, 61, and three other partners. The firm initially focused on creating then-unheard-of computers that could process digital images, selling their products to studios, astronomers, medical labs and defense contractors.

In 1989, it produced one of the first digital cameras used in America to photograph products for commercial catalogs. But the 300-pound cameras were costly and the market small, Boydston said.

Technological advances in using the light spectrum to enhance digital photography have guided Megavision’s turn toward specialized photography, he said. Infrared imaging works like a magnifying glass in unearthing text or images wiped off of parchment and reused by economy-minded ancient scribes.

The Getty Museum, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the National Institute of Art and other major museums are interested in the technology, Boydston said.

“It’s not a big market,” he said. “But it’s very cool and fun. It feels good to be a part of protecting and conserving cultural heritage.”

Saillant is a Times staff writer.

catherine.saillant

@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.