E-voting may be scarier than hanging chads

WASHINGTON — After the 2000 presidential election in Florida exposed the dangers of relying on punch-card ballots and other vintage voting systems, the federal government spent more than $3 billion to help state and local authorities overhaul the way Americans record their votes. When the polls open for Tuesday’s midterm election, 90% will be equipped with new high-tech systems.

But instead of bringing the accuracy, efficiency and reliability of the corner ATM, the wholesale makeover of the nation’s voting system has brought a new set of concerns: the possibilities of software bugs, freeze-ups, vulnerability to hackers and new forms of human error that could bring their own chaos and controversy.

In Maryland, for instance, doubts about the state’s touch-screen system are so serious that Republican Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. has urged voters to cast absentee ballots instead of going to neighborhood precincts. And in Pennsylvania, one-third of voters believe it would be easy to rig touch-screen machines to change election results, a recent university-sponsored poll found.

Both states are battlegrounds in the struggle for control of the Senate.

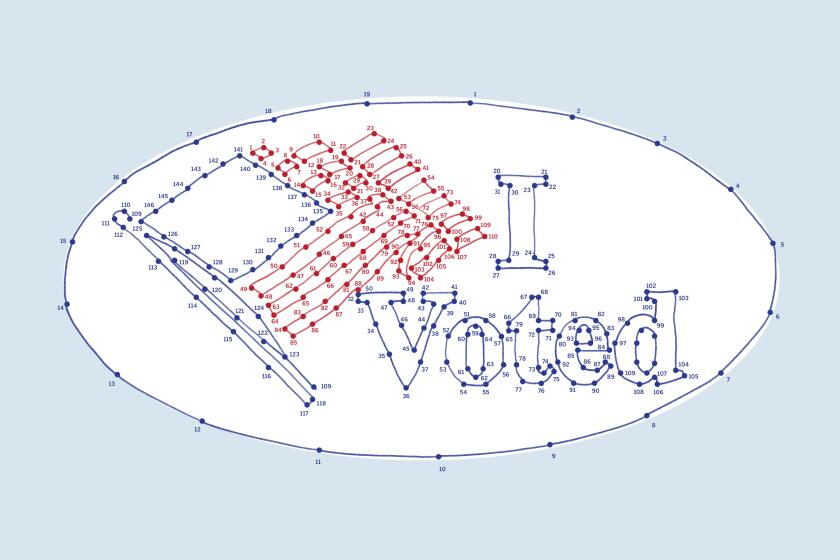

The six states that are considered most likely to determine which party controls the Senate all have adopted touch-screen voting systems, but they differ widely in the safeguards they require. According to the nonpartisan Election Reform Information Project, four of the states don’t insist on what experts consider the most fundamental protection -- a paper trail.

Though Missouri and Ohio mandate a paper backup of each vote, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Virginia do not. New Jersey’s decision to require paper backups will not be fully implemented until 2008.

Meanwhile, questions have been raised about the reliability of Ohio’s paper backup. An audit of a primary election this year in the Cleveland area found that the machine-counted vote total didn’t agree with the backup paper ballots. Because of printer jams and other problems, the paper count was significantly lower.

“The election system, in its entirety, exhibits shortcomings with extremely serious consequences, especially in the event of a close election,” analysts from the Election Science Institute said in their report to Ohio officials.

Though the old voting systems were far from uniform -- or free from errors or corruption -- the stakes in next week’s elections to decide who controls the House and Senate, as well as the statehouses and legislatures, are too high to shrug off the possibility of serious problems.

‘National security’

“This issue is a matter of national security,” said computer scientist David Jefferson of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “The legitimacy of government depends on getting elections right.”

Experts say many of the problems spring from the fact that the federal government did not impose strict security and accountability standards on the burgeoning industry that makes electronic voting equipment.

“It’s all been left up to states and local jurisdictions,” said Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), who said she intended to pursue hearings on electronic voting regardless of which party won. “In my own view,” Feinstein said, “there should be some national standards that everyone has to adhere to.”

She said she would support mandatory paper backups and random postelection audits of precincts, comparing paper ballots with machine tallies. Such safeguards are in place in California, although some critics say the state should audit a higher percentage of precincts.

Other federal officials say voluntary guidelines are enough.

“Election officials all over the country take great precautions to secure this equipment,” said Thomas R. Wilkey, executive director of the Election Assistance Commission, a federal agency Congress created in 2002 to help the states.

Federal guidelines call for extensive checking of electronic voting machines before delivery, Wilkey said. The testing is done by contractors; states and localities usually perform their own testing too.

But Jefferson, the Livermore computer scientist, said manufacturers pay the outside companies that conduct tests. The testing results often remain confidential, and manufacturers also claim trade-secret protection for their software.

“We are trying to run open, transparent elections on secret, corporate-owned software, and that to me is a fundamental contradiction,” said Jefferson, who also advises California officials on electronic voting.

Manufacturers respond that their software is reviewed thoroughly and that state officials can have access under confidentiality agreements.

Four major firms divide the market: Diebold, known primarily for its ATM machines and bank safes; Omaha-based Election Systems & Software; Texas-based Hart InterCivic; and Sequoia Voting Systems, the Oakland company currently embroiled in a controversy over whether its owners have links to Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez.

It’s inaccurate to say the software isn’t reviewed, said David Bear, a spokesman for Diebold.

Earlier this fall, however, computer scientists from Princeton University released an analysis of the widely used Diebold AccuVote-TS machine. They refused to reveal who gave them the machine, but reported it was easy to hack.

They were able to install software that changed votes from one candidate to another without leaving signs. They were also able to reprogram the machine to erase vote counts. And poll workers could unwittingly spread such viruses from one machine to another, they said.

Diebold, in a press release, dismissed the Princeton study as “unrealistic and inaccurate.” Bear said such tests don’t resemble a live election, with its shifting political currents and such traditional safeguards as poll workers of both parties at polling places, along with local police in some cases.

There is no evidence that such computer attacks have been carried out in live elections, but Edward Felten, one of the Princeton scientists, said a poll worker, delivery person, or warehouse employee could install malicious software without detection.

“It takes less than a minute,” Felten said. “You put in a key and open a little door. You push a button and pull out a little credit-card-sized memory card. Then you put in a different card. You push the power button and wait until the machine boots up. Then you remove the memory card you put in and put back the original one. You don’t have to be an expert to do the installation of the virus.”

ricardo.alonso-zaldivar@

latimes.com

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.