A Surprise in the Ring

Is it OK for girls to box?

Well, yeah, mija, they do,

he answered. Sure, it’s OK for girls to box.They were sitting on the bed in his cramped apartment, faces lit by a flickering TV, eating pizza, watching a pro boxing match. Seniesa loved to watch fights with him, loved the way boxers settled their differences, using fists to express what was inside. She was just a kid, a girl enthralled with a man’s sport, but she wanted to express herself like that.

Dad? Can I box? Can I learn how to box?

Joe Estrada was shocked, he would remember afterward, but he didn’t want to let his daughter down, not with what they had been through. Yeah, he said, eyes still on the TV. Sure, mija, you can do that, if you really want to. I’ll take you to a gym in a couple of days. I promise.

He didn’t mean it. Boxing wasn’t for girls. Not for his girl, a pretty one with thin bones, a delicate nose and rosy lips. He had lived by his fists, both on the streets and in prison. All he wanted was to protect her. For weeks, he did nothing to make his promise real.

But she grew adamant. She read a book about Muhammad Ali, got a poster of him and tacked it to her wall. She admired his confidence, the way he would not back down, just like her father, she would proudly say, and the way Ali had grown up, just as she had — an outsider looking in. She wanted to become a champion boxer, bold and strong, just like Ali.

Besides, if her father trained her, he would be with her, no matter what. Both needed that, desperately. They needed it to save each other.

The more he put off boxing, the more she pressed.

Finally, guilt got him. One Monday afternoon, he drove her to a gym on a busy street in East L.A. When he parked, she sprinted from the van to the entrance. They walked inside, unsure what was next.

Do you train kids here? Joe asked.

The manager looked down at Seniesa, leaning against her father’s side. How old is she? he asked.

Eight, Joe said. Almost 9.

She’s too small,

the manager said. We’ll train her, when she’s 13.

She walked from the gym with her head down. Joe tried to console her, but actually he couldn’t have been happier. Good, he thought, that’s the end of this boxing thing. Then, inside his van, he looked at her and saw her staring out the window.

What’s wrong, mama? he asked.

She couldn’t speak. Tears filled her eyes.

It hit him then how much this meant, how badly she just wanted the chance to step inside a ring and put gloves on and let go.

A few days later, deciding to try once more, he took her to a gym near her home where a group of boy boxers trained.

One of their coaches had grown up with Joe. Two decades before, they were in the same gang. Then Joe Estrada and Paul Gonzales took different paths. Joe scuffled along the gutter. Now 42, he had climbed out, but he could easily tumble back, leave Seniesa, even go back to prison. Gonzales, for his part, had risen from the gang and the projects and become a famous boxer.

Joe and Seniesa approached him, near the ring.

Puppet? Is that you? Gonzales asked, calling Joe by his gang name. He had long figured Joe was in jail — or dead. When he remembered Puppet, he thought of a young man with hair below the shoulders, roving eyes and a tattoo reading “Maryann” burned into his right forearm.

Before him now stood another man: just plain Joe, hair closely cropped, eyes firm, the “Maryann” X-ed out and his gang tattoo covered by a flower, heart and cross. And then there was the surprise, peeking from behind him, a small girl with smooth, light brown skin and hopeful eyes.

Paul, this is about my daughter, Joe said. She wants to box. She practically dragged me down here.

Seniesa was too shy to look him in the eye.

Gonzales was stunned. He would never forget it. She wants to be a boxer? he asked. She’s a beautiful little girl. Why on earth would you want her to box? In his heart, though, Gonzales knew he could not say no. Figuring he owed Joe, he swallowed his doubts.

Sure, he said,there’s a place for your girl here.

The trainers found Seniesa (pronounced Seh-NEE-sa) an old pair of gloves, showed her a few simple defensive moves and a basic punch. It was but a few days later when she stepped into the ring to box for the first time. Joe felt relief; he was certain she would be hit and then give up. After all, her opponent was a boy. To Seniesa, it was riveting. She saw the boy, about her size, standing in the corner across from her. She saw men hanging on the ropes, watching, wondering what would happen. They made her nervous. She heard one of them yell:Attack him, attack him, go forward, see what it’s like!

So she hit the boy.He smacked her back.

She backed off, uncertain, leaving an opening. He released a hook that plowed into her stomach.

Air sucked from her lungs. She couldn’t breathe. She bent over.

Joe gripped hard on the ropes, struggling to keep from leaping in and calling it off, struggling to keep himself from lecturing the boy: Hey, kid, what the hell are you doing, hitting my little girl like that?

Seniesa heard one of the men shout: Breathe from your stomach, girl! From your stomach!

She breathed in once, she breathed in twice. She stood up straight, like a dreamer rising from a nightmare.

She zeroed in on the boy, her small fists a blur: whapwhop-whapwhop-whapwhop.

He tried to shield himself, but now Seniesa was angry, and her blows kept coming. Whapwhop-whapwhop. Her fists moved faster than his arms. Whapwhop. She saw his legs go shaky.

Stop! A trainer yelled, applauding with the others. Nobody wanted to see the little boy get hurt.

What Seniesa felt was more than good: It was unforgettable. She walked over to her father and hugged him.

He caught himself beaming. My little girl, he thought, she can fight.‘Mija, aren’t you afraid?

he asked as he drove her home to her mother’s apartment.You’re the only girl out there. Boxing is hard, mama.’

‘No, Dad,

she said. I’m not afraid.The little boy Seniesa pummeled never showed up to box again.

The Only Girl in the Place

She was a surprise. I had set out to write the story of a boy, near manhood, full of promise, one step from making it big as a boxer.I searched the weary Latino neighborhoods of East Los Angeles, scattered with boxing gyms. One was fashioned from an abandoned jail, another from an old building that rose from the street like barracks, another from a run-down church where the pews had been replaced with a large canvas ring, and still another from an old body shop with walls splintered by bullets.

They were filled with young men. Some fought because the boxer, proud, tough and loyal to the craft, was so revered in these parts. Some fought because they had been pushed to turn their machismo into something useful, even if it meant taking blows, countless blows, again and again. Some were tender and some were hard. Some were high school kids with stubble chins, tough nicknames and new tattoos, and some were children as young as 6.

The gyms of East L.A. have produced a long line of great fighters. Paul Gonzales was one. Richie Lemos, world featherweight champion in 1941, was another. The most recent and most famous was Oscar De La Hoya, a world titleholder in six weight classes. But for every fighter who has made himself into a name, scores upon scores have tried and failed. When I stopped by the Hollenbeck Youth Center, I heard about every young man who was training there. I was impressed. Each showed confidence and hustle and hard punches. In a loud, bustling arena that smelled like old socks, I watched for hours, searching for the next De La Hoya.

Then, one day, in late August of 2002, my attention drifted past the boys and past the ring. Over there was a girl, the only girl in the place.

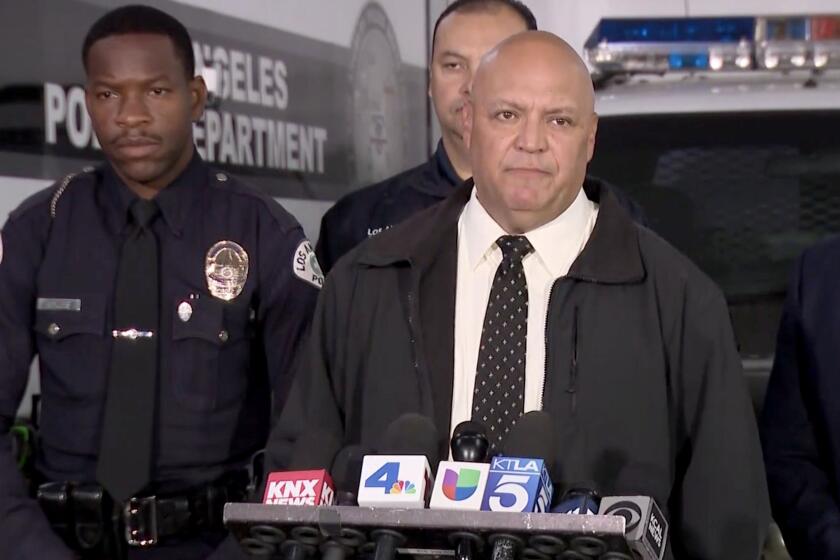

Her fists sliced through the air, and her feet skipped lightly as she punched a heavy bag filled with sand, dangling from a rafter by a chain. Next to her, eyeing every move, stood a thin man wearing a T-shirt with the sleeves torn off. Seniesa and Joe. I hadn’t imagined this. She was not a teenager, not even a he. I knew that female boxers fought professionally. There were movies about them. But I did not know that girls still in grade school boxed, their eyes fixed on future fame, just like the boys.

Intrigued, I walked over and sat on a wooden box. Joe smiled but didn’t say a word. Seniesa worked on a single punch, a round right hook. She peered over her red gloves at the bag. When she was ready, she bent her knees, corked her body, first to the right, then to the left, and let her thin arm release. WHUMP!

Her punches were solid, smooth, well-coordinated, bringing to mind the form of good male boxers. I decided to come back. Soon, I became a regular. As time passed, Seniesa and her father began to confide in me. I learned that this small girl not only wanted to be in the ring, she needed to be there — not just for herself, but for her father as well.

She had challenges far bigger than her next fight. Her neighborhood, for one, where kids got shot for as little as standing on the sidewalk. Her mother, for another, who didn’t really want her to box. Her brothers, who always seemed to be on the edge of trouble. And her uncle, a turbulent man who lived close to trouble himself. Her life was filled with unpredictability, sneak attacks, ambushes and obstacles lurking to surprise her.

Even her own father could be a problem. He was an ex-street gangster, ex-doper, ex-convict. He was a father who, for all his goodness with her, was only one more angry confrontation away from going back to prison. Then she would lose him, maybe forever. Still, he towered above everything else in her life. If not for him, she would not be here at this sweaty gym.

But a girl?

I thought she’d quit. What girl could want the loneliness she would find in the shadows of a sport so very male?

Then I listened to the sound: WHUMP!

The girl.

It was her fist, plunging into the bag, swinging it in all directions. Seniesa possessed a remarkable punch. She reared back and hit the bag again. WHUMP! This girl — oh, but this girl had power. WHUMP! I shuddered. The sound of her blows, so solid, persuaded me to forget about boy boxers.

I stopped my search for a new De La Hoya. He paled beside this little girl, her dreams and her courage, fighting to redeem her father. She knew that he needed her to help him stay straight, as much as she needed him to train her to box.

Life in ‘the Zone’

Growing up, Seniesa Estrada had found there was a lot to learn about her father.He came from Tijuana, where he and his mother lived in a dirt-floor shack with no bathroom and no running water, where a chicken from the backyard was a feast. In Los Angeles, they settled in Aliso Village, a crime-ridden housing project near downtown.

By 11, he had joined Primera Flats, a gang that “jumped him in” by testing how much of a licking he could take. In what became a trait for life, he fought back — not just to survive, but to dominate. He called it going into “the zone,” an anger that built and built until finally he snapped, feeling nothing but rage and raw energy. It turned him into one of the toughest fighters in the neighborhood.

At 15, he was an enforcer and a drug dealer. When he wasn’t fighting, he was selling: weed, acid, PCP, uppers, downers, crystal meth. He snatched purses, robbed grocery stores and stuck up jewelers. He was arrested, jailed, then got out and started selling, fighting and robbing again.

Once, he would recall, an enemy gang tied his ankles to the bumper of an Impala and dragged him through a park. Pavement ripped at his flesh until, somehow, the rope snapped and he got away. Paul Gonzales saw him afterward and would remember, “He had his shirt all tore off, and his back was just thrashed.” Joe would recall two other close calls: When a rival held a pistol to his head and pulled the trigger. Click-click; it jammed, and he escaped. Then, when he was shotgunned by a tough from the 3rd Street Gang, ricochets crashing around his head. He held his best friend, who was hit and struggling to sip air. The friend died in his arms.

Those days stayed with him like scars. Dangerous as they were, they suited him. What he liked most was to square off with bare fists at Pecan Park, two street gangsters on the grass, the violence contained only because everyone in the circle around them was armed. Nothing, not even being with a woman, made him feel better than standing firm, sinewy, olive-skinned, with piercing eyes, just him against the other guy, hitting, being hit, the joy of landing a stiff punch behind an ear.

It was a small step from there into “the zone.” Once, in a brawl over one of his girlfriends, a challenger crashed a crowbar over Joe’s brow. Anger engulfed him. It built until he lost track of who he was, where he was and what he was doing. He wrested the crowbar away, rose and chased his assailant. He tackled him. He lifted the crowbar high and brought it down on the other man’s head.

That was Joe the terrorista. Then there was Joe the Robin Hood, as he would come to call himself: charming, smooth, cool, doting on his mother, bighearted like her, doling out money from his drug sales to anyone who needed it, buying toy trucks and Barbie dolls for neighborhood kids.

Like his mother, he was meticulous: He wore spit-and-polish Stacy Adams shoes, crisp Pendleton shirts and pants with a crease he ironed himself, perfectly down the middle, just so.

Long before Seniesa was born, drugs took her father hostage for the first time, and the drugs tortured and defeated him as no back-alley thug ever could.

His undoing was heroin. He could not say no to the way it made him feel. When he was 22, heroin turned his hair stringy and wild, his face pasty, his body bone-thin. The stone-cold gangster, the sharply dressed street tough, became a strung-out junkie.

Most mornings, he found himself on the outskirts of Aliso Village, by a liquor store at the corner of 1st Street and Utah, under shot-out street lights and shards of glass, shaky, desperate, willing to do anything for another fix.

Sometimes a teenager ran by in a gray sweatsuit and a black cap. It was Paul Gonzales. He, too, was in Primera Flats, but with help from a street cop who coached him, he also was an up-and-coming boxer, training with an eye on the Olympics, rising before dawn to jog from the projects to downtown and back.

Puppet, you all right, man? Gonzales asked one morning, slowing to a walk. He would remember feeling bad, because he had always looked up to Joe.

Doin’ OK,

Joe replied. Hangin’ in there.

Joe, you gotta get clean, man. You gotta get off that stuff. It’s killing you.

He knew Paul was right. He watched him run off, across the 1st Street Bridge, toward the downtown skyscrapers peering through the morning fog. Good Lord, he thought, I could have been like Paul. If I didn’t love the gangs and the streets and the drugs so much I could have been a boxer.

Not long afterward, Seniesa’s father went to the penitentiary.

The reason is burned into his memory and was laid plain at his preliminary hearing. In late 1979, a woman in Aliso Village bolted from her bed. Someone was breaking into her house. As she reached to call the police, a Primera Flats gangster known as Pee Wee pushed a .38-caliber pistol into her face.

I’ll shoot.

She looked up at Pee Wee, then saw Joe. She knew his mother and had known Joe since grade school. I don’t know why you are doing this,she said.

Pee Wee demanded her stereo, her TV, her money. Bitch, he said. I will shoot you.

That was more than Joe could take. Hey, Pee Wee, he said.Don’t shoot her, I know her family.

From there, Joe’s recollection and the woman’s differ. Joe said he up and left. But she swore otherwise: Joe and Pee Wee looted her apartment.To avoid trial, Joe pleaded guilty to robbery. He was already on probation for another stickup. “He cannot function in the community without resorting to criminal behavior,” a probation officer told the judge, who sentenced Joe to three years in California State Prison at Susanville.

Prison was tough. He raged and fought to stay alive. But it was good for one thing: It got him off heroin and helped him gain a semblance of self-control.

Back on the streets in time for the 1984 Summer Olympics, Joe stood among the spectators at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena to watch Paul Gonzales in the ring, fighting the way Joe wanted to fight. Gonzales won a gold medal.

Twisting Out of Control

Even before Seniesa was born, her father had a feeling.He had married Maryann Chavez, a girlfriend from Primera Flats, who stuck by him through all the drugs and prison, and they had two sons. But now, when Maryann got pregnant again, Joe felt deep in his soul that this was a girl.

In anticipation of her birth, he gave her two names: Seniesa, after the daughter of a friend in his gang, and Carmen, after his mother. He crawled on his hands and knees, dousing the bathroom floor with Pine-Sol and using a toothbrush to clean the corners of the nursery where his little angel would sleep.

She was born June 26, 1992, at White Memorial Medical Center in Boyle Heights. For all his eagerness, Joe missed the moment. Maryann had begged him to go call her father, to say the baby was coming. He ran down a hallway to a phone booth, and Seniesa slipped suddenly into the world. When Joe walked back in, he saw a nurse with a baby in her arms, wrapped in a soft blanket.

Yes, he said, holding her. A girl. My little girl.

She weighed 6 pounds, 11 ounces. Her face was round and pudgy, her scalp matted with brown peach fuzz. She wailed like a banshee.

He looked into her amber eyes. Nothing had ever come close to this. He felt warmth. Certainty. Pure love. With Seniesa, he would carve out a new and special role, a role he would cling to like hope itself. He would be her guardian, the protector of his little girl.

She would need one. Home was in El Sereno, an enclave in eastern L.A. divided street after street by a handful of gangs. He would see to it that nothing would hurt her. He rose in the dead of night when she cried, three, four, five times, to feed her, hold her and place her at his side, rocking her back and forth, back and forth.

In the morning, he dressed her in a blue bonnet and lay her on a pillow in the living room. You are going to be special, little mama,

he whispered. Special. In the evening, he put her on his chest and sat back in his La-Z-Boy and watched boxing, describing the action, blow by blow, long before she could understand.

One afternoon when they were alone, she struggled to her feet. She gave him an unforgettable look. Her legs shook. She clung to the top of the coffee table. Slowly she began to tumble. He wrapped his hands softly around her.

Try again, mija, he whispered. Her face tightened with determination as she worked to regain her balance. She took a right step, a left.

That’s it, little girl. Come on, mija, come on, keep going.

She took a few steps more. Only then did she hesitate. Again she began to pitch backward. He caught her. Her father would not let her fall.Not long after that came her first word. He was there to hear it, in the kitchen one morning as he made a bacon-and-cheese omelet.

Daddy.

How it felt, seeing those first steps, hearing that first word: Daddy. As if he were a good man, a decent and even honorable human being.

For his new family, Joe worked hard with his brother Rick at the family shop, building signs and installing them at strip malls all over the city. After the kids were born, Maryann stayed home, and it took all Joe could do to make enough money. Sometimes he left work at midnight, then rose before dawn to drive to another job.

To fight fatigue, a co-worker offered cocaine.

Joe said no. He knew where drugs could lead.

But then, when Seniesa was just a few months old, he gave in. One line led to another, then another. After a few weeks, he was hooked again, sucking thick ridges of coke up his nose seven times a day.

Even then, he tried to be a daddy. He kept phoning home from work. How’s she doing, is she OK? he asked.Is my baby OK?

In front of the TV, she would sit with him, lying in his lap, curling under his chin, cooing, even when he was high. For the backyard, he got her a swimming pool. Its sky-blue metal sidings rose 4 feet above the ground. Everyone wanted to splash around with Seniesa, teach her to swim. But there was only one person who could coax her into the water without a struggle: her father.Inevitably, he grew erratic. Maryann began to fear him. Their quarrels grew ugly. When he came home, she huddled with Seniesa and the boys in a bedroom, cordoning him off in the living room, demanding he stay there and sleep on the couch.

The night before Seniesa’s first birthday, he went out smoking, drinking and snorting. He arrived late for her party. Head throbbing and in a cold sweat, he slunk through the celebration, a knot in his stomach. Everyone could see he was back to his old ways. And they knew he was failing as a father. It was Maryann who tied the piñata to an oak tree, grilled the hot dogs, poured the sodas and fussed over their daughter. He stayed on the periphery — at a party for his little angel.

One night, when he came home from a long work trip, Maryann had left him. She took the kids. The house was bare. Everything of any importance was gone. Worst of all, Seniesa was gone.

He stopped working. He twisted out of control. Soon enough, he was back on heroin.

Seniesa didn’t see him for months. Then, when she was about 3, she began asking for her father.

Her mother, thinking it would be OK, let her visit him.

Seniesa saw a bare floor, a mattress in a corner of the living room, covered with a few blankets. She met pushers, junkies and street gangsters. Some had enemies, and they were turning her old home into a death trap. Once, when she was not there, an addict was killed on the front steps.

Joe tried to protect her. When she came to visit, he told his housemates to put away their drugs and guns. He gave them a few bucks, told them to leave, go buy some pizza. Nobody, he said, was to let anything happen to his little girl.

But he couldn’t bring himself to change, even for her.

One day, when Seniesa was not around, he asked himself: Why on earth go on? He couldn’t find an answer.

He slumped into a chair, determined to stop the pain.

He put a chalky chunk of heroin into a spoon with a dab of water and heated it with a match until it bubbled. He plunged a needle into the crook of his arm, pushed on the syringe and let the concoction smooth through his body.

He would forever feel the shame. As the heroin enveloped him in its warmth, he saw an image of his little girl, in a floppy white hat with a rose on top, just like the one she wore in his favorite photograph. He felt heartbreak. But he wasn’t done. He stumbled into the bathroom and shot up again, knowing well that a second dose might be enough to kill him.

Two junkie roommates found him. They filled the bathtub with water and ice. They dumped him into it, pulled him out, slapped him, propped him up and walked him in circles on the living room floor.

He slept, then woke, sore, spent and thankful to be alive. He had to leave, flee, straighten out. He needed his family back. Needed his little angel.

For months, he lived like a stray dog, with anyone who would take him in. He slept on couches, in cars. He holed up in a studio apartment on a run-down street near the clanking East L.A. train yards.

His brother, Seniesa’s Uncle Rick, took him to church. Even before the sermons, Joe was in the bathroom, snorting coke.

Finally, one night, he sat on his bed in his dim room, all alone. He knew that if he did not stop drugging, he would lose his kids, lose his life, lose Seniesa forever.

He opened his black leather-bound Bible to John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son “

God did this for me, sacrificed his child, Joe told himself, in wonderment. For me, a crook and an addict. Even with all the unspeakable pain I’ve caused. Even I can be forgiven.

He felt hair rising on his arms and on the back of his neck. He stood up from the bed, feet planted firmly in the gray carpet. He clutched the Bible to his chest with both hands.

Please, Jesus, help me,

he prayed. I know you are there, just show me. He fell to his knees, tears rolling from his eyes. His words and what was happening became etched in his mind.I just want my family back. I just want forgiveness for the things I have done. I just want to prove that I am a good man.

All the while, things were not well with Seniesa. She had grown aggressive. She was snake-hip skinny, and her light brown locks flipped off her shoulder and into the air as she plowed through life, attacking it, a one-girl storm. Again and again she crashed her bike, once flipping herself over the handlebars. Again and again she ran into her mother’s sliding glass door. She slammed her forehead against it in full sprint, as if on purpose.To Maryann and Joe, she seemed angry, frustrated perhaps with his struggle. How could he protect her if he couldn’t save himself? Maybe she was afraid. He was hardly around; maybe she feared that someday he might never be.

A Magnet for Fighting

Somehow, slowly, Seniesa’s father found the strength.Maybe it was his newfound faith. Maybe it was the damage he saw in his family, the pain to Seniesa. Maybe it was all of this, in an overwhelming way. Somehow, he no longer wanted to go out at night and find trouble. It took time, but Joe finally began to confront his past.

Seniesa was about 6 when he started to turn around. He kicked drugs and went back to work at the sign shop. There was too much hurt between her parents for reconciliation, but not between Joe and the kids. He saved money, bought a van and took them to movies, to Disneyland and to Dodger games. He helped coach the boys’ baseball teams.

But he lived alone and was lonely. Sometimes, when he called Maryann’s apartment on weekends to see if the kids wanted to come over, the boys preferred to stay home.

Not Seniesa. She always begged her dad to pick her up.

When he didn’t call her, she called him. Daddy, Daddy, when are you coming to see me?

With him, she was sweet and playful. Shy, even. And Joe noticed that when he was around more, she stopped inflicting her aggression on herself.

Instead she turned it outward. She began attracting fights like a magnet. At home, at school, at parties, she wrestled, scratched, clawed and tried to lay a good whipping on any kid she thought had slighted her. Once, she bloodied a little girl’s face so badly that Maryann swore she would never take her to another birthday party.

Then there was the day Maryann and Seniesa waited in line at the Social Security office near their home. Maryann couldn’t believe her eyes. Seniesa motioned to a little girl, waving at her to come closer.

What’s going on? her mother asked. Stop acting so embarrassing.

She’s staring at me. I don’t want no one staring at me,

Seniesa said. She scowled at the little girl, who stood near her own mother and stuck out her tongue.

Seniesa was ready to brawl. Want some of this? Come get it. I’ll kick your butt. You don’t want to mess with me.

None of this surprised Joe. Sure, he thought, she needed to calm down, but there was something about her courage that made him happy. “Her way of reacting to frustration, to fear, is like my own,” Joe would say, looking back. Her way of reacting was to fight.

So it was that at his apartment one day in late 2000, while they sat on his bed, as they often did, eating pepperoni pizza, napping and watching professional fighters on TV, she asked if she could box. Would he teach her?

At 8, she was old enough to know what might happen to her father if he ever went back to fighting on the streets.

It was too much, perhaps, to expect either of them to have wondered if she was asking to fight in his place. No, she seemed to want this for herself, to become a champion. But did she realize that this could be a way to show the world that her coach — her father — was in fact a good man, despite his past? That she could redeem him?

Whether she realized any of this, it was true that she would be making something good out of the aggression she felt inside.

Her father wondered if it would be too much. Shouldn’t she be hanging out with her girlfriends, playing hopscotch and double Dutch?

Seniesa wanted no part of that.

She wanted to be a boxer.

*

Monday

Seniesa’s reputation grows, but family troubles and a lack of competition jab at her morale.

*

About This StoryKurt Streeter met Seniesa Estrada and her father, Joe, in August 2002. Over the following 2 1/2 years, Streeter and photographer Anne Cusack spent hundreds of hours with them and with their family members, friends and acquaintances. Streeter interviewed and observed Seniesa and Joe extensively, together and individually. He also interviewed and observed their friends, their family members, Seniesa’s teachers, her trainers and other boxers, their parents and their trainers.

Cusack photographed most of these subjects. Together, Streeter and Cusack watched and photographed Joe and Seniesa while they trained at boxing gyms in East Los Angeles. They watched Seniesa train outside the gyms and joined her and her father at boxing tournaments throughout Southern California and Arizona. Streeter stood ringside and observed Seniesa’s tournament fights. In Arizona, he visited and interviewed her principal opponent and the opponent’s family.

He used police reports, court documents and prison records, as well as witness accounts, to corroborate Joe Estrada’s background. Streeter visited Estrada at his mother’s house and later in his mobile home in her backyard. He frequently visited Seniesa, her mother and two of her brothers at their home in the Los Angeles neighborhood of El Sereno. Streeter also observed Seniesa during class and on the playgrounds at her elementary and middle schools.

Quotations in this series are designated in two ways: Those heard by the writer are enclosed in double quotation marks. Those recalled by others in interviews are in single quotation marks.

*

Notes on Chapter OneSeniesa asks if girls box: From interviews with Seniesa and Joe in 2003 and 2004. Their words are as they remember them.

Watching TV in Joe’s apartment, including Seniesa’s request to learn how to box: From an interview with Seniesa and Joe in May 2004. Her words are as they recall them.

Joe’s concerns and his false promise: From an interview with Joe in May 2004. His words are as he remembers them.

Seniesa’s insistence that she be allowed to box: During an interview with Streeter in May 2004, she showed him her Muhammad Ali book and her poster. Her words and her father’s response are as they recall them.

Seniesa and Joe try to find a trainer: From Seniesa and Joe. Streeter accompanied them to the gym that would not accept her and they described what happened. The words Joe spoke to the trainer and the trainer’s response are as Joe and Seniesa remember them.

A crestfallen Seniesa returns to Joe’s van: From Seniesa and Joe. His words are as they recall them.

Seniesa and Joe enter the Hollenbeck Youth Center, looking for Paul Gonzales: Joe’s introduction is as Gonzales, Seniesa and Joe recall it. Gonzales’ surprise and his recollection of what Joe had been like in the past are from an interview with Gonzales. The description of Joe and Seniesa as they spoke to Gonzales is from Seniesa, Joe and Gonzales. Streeter interviewed Gonzales in August 2003 and May 2004.

Exchange between Joe and Gonzales about Seniesa’s learning to box: From Gonzales, Joe and Seniesa as they recall it.

The trainers give her gloves and teach her a simple punch: From Seniesa, Joe, Gonzales and an interview in August 2003 with Ronny Rivota, a trainer at the gym.

Seniesa sparring for the first time: From Seniesa, Joe and Ronny Rivota, who described in detail what they saw and heard. Joe’s reaction when Seniesa was hit is from Joe. It is Rivota who shouts breathing instructions. His words are as they were recalled by Rivota, Joe and Seniesa. Her anger as she punches the boy is from Seniesa.

Seniesa’s elation and the hug from Joe: From Seniesa and Joe.

Driving home, Joe asks Seniesa if she wants to keep boxing: From Seniesa and Joe. Their words are as they remember them.

Description of the East L.A. boxing scene: From Streeter’s observations. The boxing gym inside an abandoned jail is at the old Los Angeles city jail. The building that rises from the street like barracks is the Hollenbeck Youth Center. The gym in an old church is at the Oscar De La Hoya Youth Center. The gym with walls splintered by bullets is the 1st Street Boxing Gym.

Description of Joe’s childhood in Tijuana: From an interview with Joe in April 2003 and an interview with his brother Mark Aguirre in May 2004.

Joe’s early gang life: From Joe and interviews in April and May 2004 with those who knew him in his teens and early 20s, including Mark Aguirre; Seniesa’s mother, Maryann Chavez; Maryann’s sister, Rosa Espinoza; Seniesa’s godmother, Alice Alvarez; and Paul Gonzales. Description of what he feels in “the zone” is from Joe.

Joe’s past as a drug dealer, robber and thief: From the probation officer’s report in California vs. Jose Luis Estrada. The report was submitted July 21, 1980. Also from interviews with Joe, Maryann and Gonzales.

Joe is dragged by an Impala, threatened and shot at by members of rival gangs: From Joe and corroborated by Paul Gonzales.

The fights at Pecan Park: From Joe and confirmed by Maryann, Alice Alvarez and Paul Gonzales. Corroborated by two former Primera Flats gang members who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Going into “the zone,” wielding a crowbar: From Joe and corroborated by the probation officer’s report used in California vs. Jose Luis Estrada.Joe as Robin Hood:

From Joe, Maryann, Paul Gonzales, Mark Aguirre, Alice Alvarez and two former Primera Flats gang members who spoke on condition of anonymity.Description of Joe, the meticulous dresser: From Joe, Maryann, Paul Gonzales, Mark Aguirre, Alice Alvarez and two former Primera Flats gang members who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Joe becomes a junkie: From Joe, Maryann, Paul Gonzales, Mark Aguirre, Alice Alvarez and two former Primera Flats gang members who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Paul Gonzales encourages Joe to get off drugs: From Joe and Gonzales. The words spoken are as they remember them. Joe’s thoughts when Gonzales jogged away come from Joe.

The robbery: From Joe; from trial testimony on March 18, 1980, in California vs. Jose Luis Estrada; and from the probation report in that case. Pee Wee is not further identified in the court transcript. Joe refused to identify him more fully to police, so he was not arrested. The words exchanged are from Joe and the court records.

Time in prison: From Joe and California Department of Corrections records.

Joe watches Paul Gonzales fight in the Olympics: From Joe and Maryann.

The desire to have a daughter and how Joe names her: From Joe.

Toothbrush scene: From Joe and Maryann.

Seniesa’s birth: From Joe and Maryann. Seniesa’s weight and description and Joe’s excitement are from Joe and Maryann. His feelings and his words are as he remembers them.

Scenes from Joe’s first months with Seniesa: Rising from sleep to check on her and dressing her in the morning are from Joe and Maryann. The words Joe whispered are as he recalls them. Sitting with Seniesa while watching boxing on TV is from Joe and Maryann.

Seniesa’s first steps, first words and Joe’s feelings: From Joe.

Why and how Joe returns to drugs: From Joe, Maryann and Mark Aguirre. Corroborated by Joe’s son Joey.

Joe’s calls home to check on his daughter: From Joe and Maryann.

How Seniesa lies in her father’s lap as he watches TV and how she allows him to coax her into the pool: From Joe, confirmed by Maryann.

Joe spirals back into addiction: From Joe, Maryann, Joey, Mark Aguirre and Alice Alvarez. Cordoning off parts of the house is from Joe and Maryann. Seniesa’s first birthday is from Joe and Maryann. Condition of the home after Maryann left is from Joe and Maryann.

Maryann takes Seniesa away: From Joe and Maryann.

Seniesa gets to see her father again, but the house is now a death trap: From Joe, Maryann and Mark Aguirre, who depicted the house and the people in it. Corroborated by a report from the Los Angeles County coroner on the homicide. The report described the home as a drug house.

Joe tries to kill himself: From Joe, who described his actions and feelings and provided Streeter with the picture of Seniesa he envisioned in his stupor. How he was rescued is from Joe, who learned about it from his rescuers.

Living with anyone who would take him in: From Joe, corroborated by Maryann, Mark Aguirre and Maryann’s sister, Rosa Espinoza.

Snorting coke in a church bathroom: From interviews with Joe in May and June 2004.

Bible scene in Joe’s apartment: From Joe, whose thoughts, feelings and prayer are as he recalls them.

Seniesa’s wild streak, bumps and bruise: From Seniesa, Joe, Maryann and interviews in May and June 2004 with Seniesa’s brothers Joey and Johnny.

Joe starts to turn his life around: From Joe, Maryann and Seniesa. Her phone calls and her words are as Joe and Seniesa remember them.

Seniesa turns her aggressiveness outward: Her fighting was described by Seniesa and Maryann. The confrontation at the Social Security office is from Seniesa and Maryann. The words spoken are as they recall them.

Joe’s reaction: From Joe, in an interview with Streeter in July 2004.

Concern about whether Seniesa should be spending time with girlfriends instead of boxing: From Joe, whose thoughts are as he remembers them.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.