In San Francisco’s North Beach, pasta, poetry and a big helping of uncertainty

San Francisco’s North Beach has seen many changes lately, but these signs suggest that its Italian-bohemian character will endure.

Before we get to the bad news, let’s agree that North Beach, the West Coast’s most-storied Little Italy and the richest vein of Beat Generation memories anywhere, can still deliver a moment the way Frank Sinatra delivered “My Way.”

As you line up for morning cappuccino among the young and old bohemians at Caffe Trieste, you spot a few who may have been present at its opening in 1956: one with bell-bottoms and a ukulele; one in a jacket that says “Rent Is Theft”; and one who is so focused on what she’s typing that she might bite through the pencil in her mouth.

As you eavesdrop on Columbus Avenue near Vallejo Street, you hear a burst of Italian, a flurry of Chinese and a smattering of Spanish, all within two minutes, all from locals.

As you shoulder through a crowd outside Golden Boy Pizza on Green Street, which has sold slices since 1978, you discover yet another line at the door of Sotto Mare, where the cioppino is king and the walls are crowded with big fish and old photos.

From here, Fisherman’s Wharf is north. Chinatown is south. And Columbus Avenue plows through at an angle, because what’s interesting about 90-degree street corners?

“This is the only real neighborhood that’s left in San Francisco,” Louis Samuels, a longtime North Beach resident, told me. “The tourists have been here forever, so they can’t [foul] it up.”

But from many angles, it looks like low tide in North Beach.

In 2017, the restaurant Rose Pistola at 532 Columbus closed after 20 years, and L’Osteria del Forno at 519 Columbus closed after 27 years. Caffe Puccini, at 411 Columbus, burned and closed that October after 28 years. In March 2018, Caffe Roma at 526 Columbus closed after 29 years.

North Beach’s retail vacancy rate ranks among the highest in the city, higher than it’s been in years. One city report calculated that 45 of 219 storefronts were empty at the end of 2018.

The empty spaces didn’t seem that numerous during the four days in early August I spent wandering the neighborhood. But people are talking and changes keep coming.

Long before HGTV glommed onto the trend, German immigrant farmers in Fredericksburg, Texas, built small, simple dwellings, called Sunday houses, for their in-town visits.

In April, producers of the long-running comic revue “Beach Blanket Babylon” — a neighborhood stalwart that has charmed tourists with gentle satire and enormous hats since 1974 — announced it would stage its last performance Dec. 31.

In July, management abruptly closed Tosca, an emblematic restaurant and bar with a 100-year history as a Columbus Avenue speakeasy, celebrity hangout and later a trendy dining destination. New owners have vowed to reopen but it’s unclear when.

Meanwhile, until at least December, the city’s Recreation & Parks department has fenced off Washington Square Park, the neighborhood’s oldest landmark and largest green space, to fix the irrigation system.

Those who wish to cry into their cappuccino now may be excused.

For the rest of us, this might be a good moment to grab a mental snapshot of North Beach before the next wave of change, to smell the garlic, grab a meal that involves tomato sauce, browse one of the nation’s most beloved bookshops (City Lights on Columbus), perhaps lay your hands on fine ceramics from Perugia at Biordi on Columbus Avenue or a custom handbag that used to be a baseball mitt at Al’s Attire on Grant. Or just drink where Jack Kerouac drank (Vesuvio Cafe on Columbus). But not as much, please.

But while you’re at it, remember there’s always someone saying how much better this neighborhood used to be.

The Ohlone were entitled to say it when Spanish colonizers grabbed their land in the 18th century, followed by gold seekers in the mid-19th, and Italian fishermen and their families in the late 19th.

All the world said it in 1906, when the great quake and fire leveled much of the city. I’m betting somebody said it again in the 1920s, when the San Francisco Art Institute moved in, putting bohemians and Italians in proximity.

By 1949, Herb Caen himself was saying it. “What’s left of San Francisco’s bohemia is centered in North Beach,” the author and columnist wrote. He went on to lament that high-priced apartments ($200 a month) were crowding out the artists.

Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Kerouac arrived a few years later, leading the most notorious invasion of poets, painters, dreamers and loiterers the city has ever seen. (That’s when Caen coined the word “beatnik.”)

All these years later, the fascination continues even as details evolve.

“This is cyclical. I’ve seen this 15 times,” said Jimmie Schein, who has put in 18 years as co-owner of Schein & Schein Antique Maps and Prints on Grant Avenue. “North Beach is simply suffering from what San Francisco is suffering from.”

The tech millionaires. The homeless. Within two minutes, Schein told me “I love it here” and “We are failing miserably as a city” — and clearly meant it both times.

“We’re always fighting in the neighborhood for something,” said Blandina Farley, who has been leading North Beach tours for nearly 20 years. A few minutes later, she pointed out a one-bedroom apartment.

“About $4,100 a month,” she said.

One night I caught up with Massimo Di Giulio at Ideale Restaurant & Bar, who recalled his arrival from Italy.

“I got here in 1974,” he said. “The first time I came to North Beach, I came to this door. It was a jewelry shop.”

By the late 1980s Di Giulio was working as a tour guide, showing European visitors the American West. He still is, and in San Francisco he tells how Italian immigrants reached North Beach in waves, region by region, over generations.

And then, “I tell them the Italians are moving out or have moved out,” said Di Giulio, who lives in nearby Richmond. “I tell them that Italian food has fallen out of favor with the young people, so a lot of restaurants are closing.”

Meanwhile, at Molinari Delicatessen, which has stood at Columbus Avenue and Vallejo Street since 1907, “It’s not the same, the way it used to be,” said head of operations Nicholas Mastrelli. “And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. ... I’m really excited.”

Mastrelli, 23, is the fourth generation of his family to stand behind Molinari’s counter. As Sinatra crooned in the background, Mastrelli told me how, as a kid helping his dad, he used to walk the neighborhood in the morning, buying bread from bakeries that no longer exist.

Now he’s adding gluten-free pasta to the inventory but still selling old-school sandwiches that bring crowds at lunchtime. Come hungry, grab a number and order the Molinari Special Italian Combo Sandwich.

Here, as tides of change roll in, are several lessons from North Beach now.

There is no beach. Once upon a time there was a beach. But in the late 19th century, as San Francisco’s leaders used landfill to create more real estate, Fisherman’s Wharf grew and North Beach found itself landlocked, with Chinatown to the south and Coit Tower rising from Telegraph Hill to the east.

Also, there are no cigars at Mario’s Bohemian Cigar Store Cafe, there are no live worms at Live Worms Gallery, and Original Joe’s isn’t in its original location and has never been owned by Joe. Nice place for a drink, though.

There is no Italian restaurant shortage. Several have closed, dozens remain, and a few are new, such as Barbara Pinseria on Columbus, which specializes in rustic Roman-style pizza. Some have great food. Some have Italian owners who arrived in the ’80s or ’90s. Some have achieved maximum kitsch through liberal use of cherubs, murals, carvings, lights and bibs.

None is a major chain operation, because that’s illegal here. And none is perfect.

So you eat around.

Show up early to beat the line at Tony’s Pizza Napoletana on Stockton Street; it promotes its prize-winning pizza margheritas by making just 73 of these gooey yet crisp pies per day, using a prize-winning recipe that includes Caputo blue-label flour and San Marzano tomatoes.

Get yourself into a deep conversation with a meatball sandwich at Mario’s Bohemian Cigar Store Café on Columbus Avenue. Linger over ravioli while Dean Martin sings “That’s Amore” over the old-school tumult of a Friday night at Sodini’s Green Valley Restaurant on Green Street. (“No decaf, no desserts, no reservations, no exceptions.”)

Nip into the calm, contemporary interior of Grant Avenue’s Ideale, whose owner, Maurizio Bruschi, came from Rome in 1986. (I liked the tortelloni and prosciutto.)

And because there’s more than one way to make great Naples-style pizza, drop into the sleek, modern setting of Il Casaro, which opened five years ago on Columbus.

Italians have seniority here, but they also have company. Step beneath the twin white spires of Saints Peter and Paul Church (completed in 1924) and admire the Italian marble and stained glass windows. Imagine Joe DiMaggio as a schoolboy running up and down the stairwells in the ’20s. Then check the schedule for Sunday morning Mass. At 7:30 and 8:45, it’s in English. At 10:15, Chinese. At 11:45, Italian.

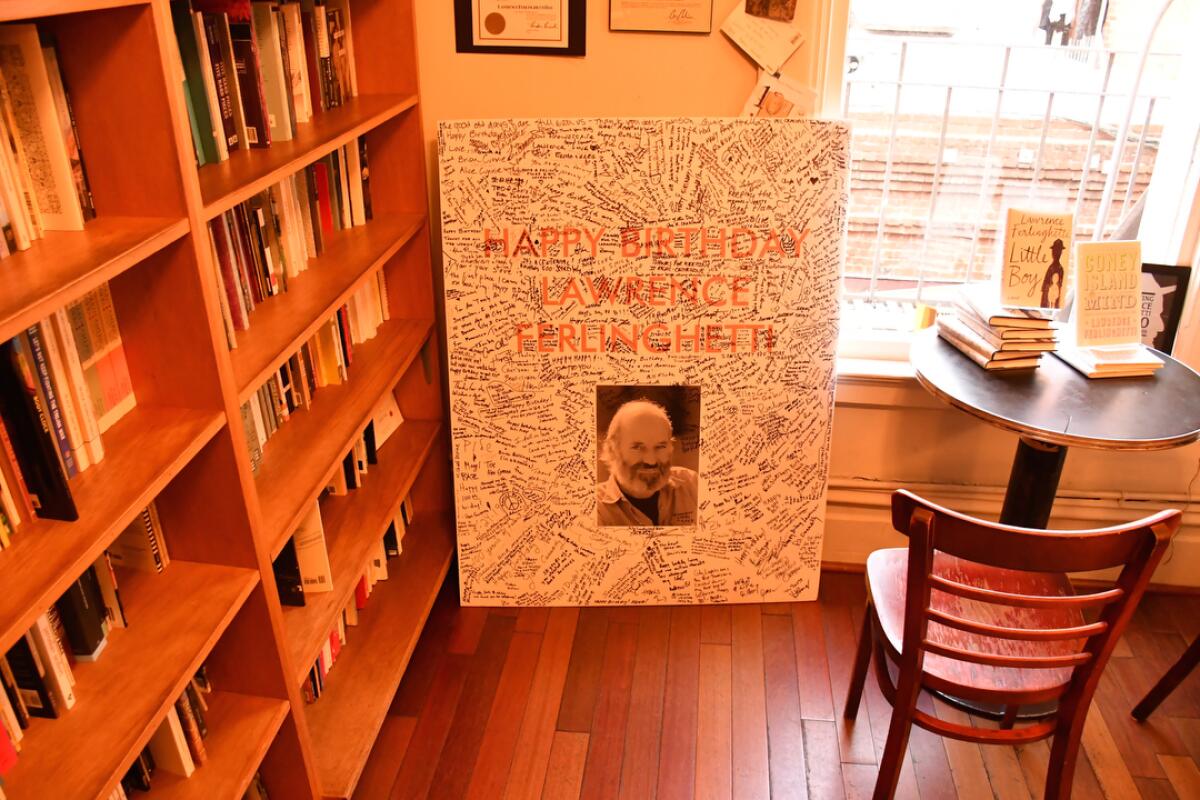

Ferlinghetti may live forever. Even if he doesn’t, his City Lights Books might. Ferlinghetti, the poet who cofounded the bookstore in 1953 and published Ginsberg’s “Howl” three years later, celebrated his 100th birthday in March. (He also published a novel, “Little Boy.”) He mostly stays in his nearby apartment while the three-level shop swarms with lovers of literature and liberal politics.

The Beats go on, including Ginsberg’s organ. Across the alley from City Lights, there’s Vesuvio Café, where Kerouac, Ginsberg, their co-conspirator Neal Cassady and many others huddled, and where precious little seems to have changed since its opening in 1948. For a perch with a view, head up the stairs. For a similarly timeworn, artsy setting with far fewer tourists, cross Columbus to Specs’ Twelve Adler Museum Cafe on the little pedestrian nook known as William Saroyan Place.

To learn a little more about the Beats and their successors, the hippies, cross Columbus to the Beat Museum, which is really more of a shop than a museum, but which has vintage hipster photos and first editions, an old mimeograph machine, one of Cassady’s shirts and an electric organ attributed to Ginsberg.

Don’t forget the focaccia. There aren’t as many North Beach bakeries and pastry shops as there once were, but I like Stella Pastry and Cafe on Columbus for coffee and a sweet, and Caffè Greco across the street for a modest breakfast. And I like Mama’s on Washington Square for a big breakfast, even though it’s not Italian and the lines get long.

And for seniority and focus, nobody beats Liguria Bakery on Filbert. The people at Liguria, a family operation since 1911, do several varieties of focaccia to go ($5-$6 for an eight-piece sheet of Italian flatbread, wrapped in white paper with twine) and nothing else. Cash only. Get in and get out.

Once the city finishes redoing Washington Square, you can have that flatbread snack on the grass while watching Chinese women do their morning tai chi. (At the moment, they are squeezed into a playground at the edge of the square.)

Beyond Columbus Avenue, rewards await. Columbus is the spine of the neighborhood, but it’s also the beaten tourist path. Upper Grant Avenue has a more pedestrian feel and browsing that draws locals to galleries and boutiques such as Paparazzi; jewelry and metal sculpture at Macchiarini Creative Design; and antique maps and prints in the snug confines of Schein & Schein.

“First map of the city!” I heard Schein cry out one afternoon as a customer considered a reproduction document from the 1850s. “You’ll notice that there’s no Columbus Avenue. They won’t put that in for years.”

And once they did, you can bet someone complained that the neighborhood would never be the same.

If you go

WHERE TO STAY

Hotel Boheme, 444 Columbus Ave., San Francisco; (415) 433-9111, hotelboheme.com. Fifteen rooms, all on second floor, with black-and-white photos from the ’50s and ’60s. Most rooms for two start at $265. Those facing away from Columbus Avenue are much quieter. Better for couples than families.

San Remo Hotel, 2237 Mason St., San Francisco; (415) 776-8688, sanremohotelcom. Dates to 1906 with quaint European feel. Sixty-four guest rooms, shared bathrooms are down the hall. (The penthouse has its own toilet.) Rooms for two $99-$189.

Green Tortoise Hostel, 494 Broadway, San Francisco; (415) 834-1000, greentortoisesf.com. As many as 125 people can sleep in the building’s 40 units, some dorm-style, some private, with bathrooms down the hall. Rates $35-$56 per person, private rooms $80-$151.

TO LEARN MORE

sftravel.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.