Instead of returning to school this fall, Mexican students will watch TV

The television has been called the “idiot box” and the “boob tube.”

In Mexico, it will soon be the classroom.

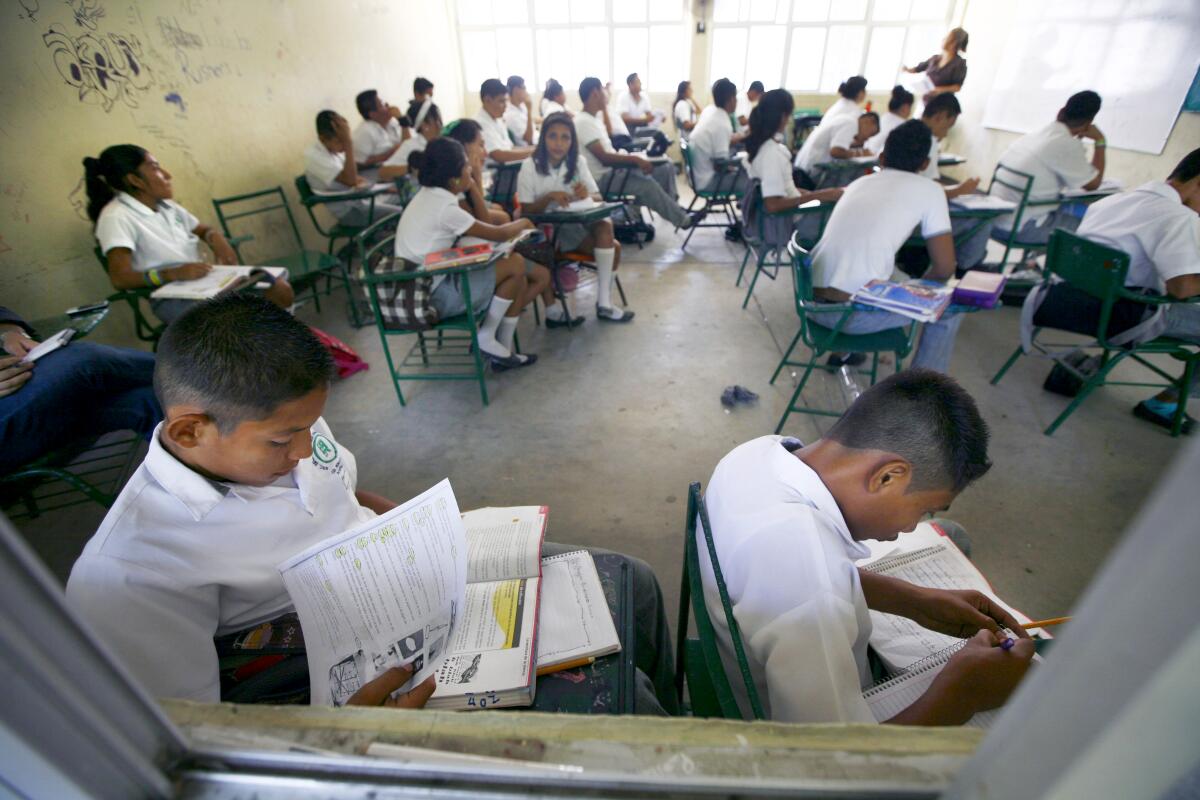

With the coronavirus outbreak showing no signs of abating here, officials have decided to keep public elementary and secondary schools closed indefinitely and have the nation’s 30 million students begin the new academic year at home.

But in a country where 4 in 10 homes lack an internet connection, online classes are not a viable option. So authorities have turned to television.

The federal government this week signed a $20-million contract with several Mexican television networks to broadcast study programs designed by education officials.

The United Nations predicts that a global recession will reverse a three-decade trend in rising living standards and thrust half a billion people into extreme poverty.

The daily classes and accompanying textbooks will be the backbone of academic instruction until it is safe for students to return to the classroom — a plan that has sparked confusion and frustration among parents and prompted fears that Mexico could lose some of its hard-fought gains in education.

Authorities acknowledge that the television is no replacement for teachers, but say it is the best way to reach most of the country’s students because 94% of Mexican families have TVs.

“The pandemic leaves us few options,” said the education secretary, Esteban Moctezuma, while promising a “robust” course of study.

Officials have yet to detail how televised learning will work, including what part, if any, teachers will play, or how families with working parents or more children than television sets are expected to manage.

“I’m panicking,” said 38-year-old Ana Laura Ruiz, a single mother in Mexico City who recently returned to the office where she works as an accountant after the city’s pandemic lockdown was partially lifted.

When students across the country were sent home in March after the virus was detected here, each school handled distanced learning in its own way. Ruiz joined a WhatsApp group with parents and teachers, who sent lesson plans and homework for their pupils.

Ruiz said she would rather continue that way than have her kids watching television.

“How will I know that my children actually took their classes?” she asked. “Who will supervise them?”

She has two children, ages 13 and 10, but only one TV at home, and she doesn’t know how they will both take classes.

“I’m worried this will be a lost year for them,” she said.

Clara Solis, a 37-year-old primary school teacher, said she had received no information about what her role would be when the academic year kicks off Aug. 24.

“Children need more specialized attention,” she said. “I’m concerned about the number of children who are not going to receive adequate care.”

Every country in the world has had to weigh the safety of students and teachers against the need to provide kids education.

In the United States, President Trump has threatened to withhold funding for school districts that don’t reopen. In Bolivia, officials announced this week that they were canceling the school year entirely after considering moving classes online but concluding that would be impossible because most rural areas lack internet access.

Israel and South Korea hastily reopened schools only to close them again after spikes in new virus cases. Denmark and Germany appear to have avoided outbreaks by greatly reducing class size and staggering the days that students attend school.

The stakes are high. Educational attainment has risen steadily in Mexico in recent years, and many now worry that some of those gains could be erased.

The share of Mexicans who have only an elementary school education or less fell from 67% in 1990 to 33% in 2015. The proportion of Mexicans with a college education more than doubled during that time, to 15%.

Malcom Aquiles, a policy advocate for World Vision, a Christian aid organization with a focus on children, said that some students who stop going to school this year may never return.

“It could trigger a lot of dropouts,” he said.

Aquiles said he was glad that authorities had decided to prioritize public health. But he worried about the impact of the new education plan in rural parts of the country, where access to television and even radio is limited, and where the pandemic’s economic impacts have already forced some school-age children to join the workforce in recent months.

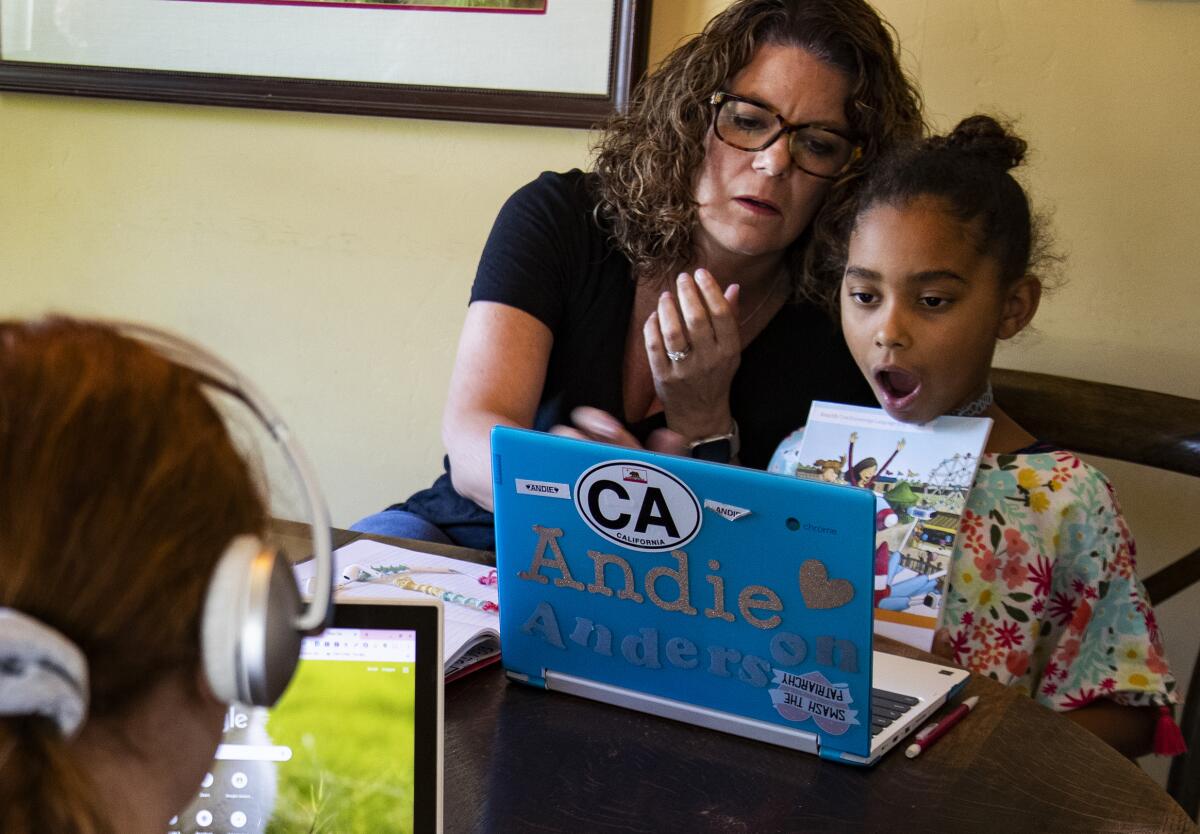

Patricia Gándara, a professor of education at UCLA who has studied the school system in Mexico, said that while televised instruction is “better than nothing,” it will undoubtedly result in more inequalities.

Two decades ago, a team of U.S. and Mexican researchers descended on Dalton, Ga., to study the growing number of Mexican immigrants who had come to work in the city’s carpet mills.

“These learning gaps, which we call opportunity gaps, will just get wider and wider,” Gándara said.

As in the U.S, where the children of immigrants are less likely to have internet access at home, it will be the poor in Mexico who suffer, she said.

“If you’re home with a parent who is well-educated and can guide you through these things, that’s pretty good,” Gándara said. “If you’re just by yourself with the television, that’s another story.”

Officials said they have a plan for the 6% of families that don’t have a television: educational radio broadcasts, which will air in Spanish and in 22 Indigenous languages.

“Nobody will be left behind,” vowed Moctezuma, who said the government will also address the issue of households where parents don’t have the luxury of staying home with their children.

“We are going to have a proposal ... to see how working mothers can be helped,” he said.

Academic instruction on television isn’t a new concept in Mexico, where since 1968 students in some rural areas have attended small schools where instruction is broadcast on TV.

The results have been lackluster. In national language exams in 2017, 49% of students enrolled in schools with televised learning scored insufficient marks, compared with 32% of students enrolled in typical schools.

“There is no substitute for the work of a teacher,” said Juan Sánchez García, an instructor at a teachers college in the northern city of Monterrey who has studied televised learning.

One problem is that there is no way to tell how many students are actually tuning in. For that reason, Sánchez said, it is essential for authorities to find ways to measure comprehension and achievement while pupils are learning from their homes.

“This is the main thing,” he said, “getting help to the students who need it the most.”

Cecilia Sanchez in The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.