He has a job: diving for dead bodies. But his family still lives in poverty

Reporting from Khanauri, India — In a remote north Indian village, Ashu Malik’s name and phone number are written in big red letters on a small shed along a serene canal.

For a quarter-century, it has been his job to recover bodies that have fallen into the canal.

When someone in a nearby district goes missing, Malik often hears a knock at the door. Police officers, investigative agencies and families have all sought the 38-year-old’s help in dealing with accidents or suicides.

Built more than 60 years ago, the Bhakra Main Line canal, which runs through four states in northern India, is a tranquil sight that is often tainted by the odor of dead bodies. The canal’s sluice gate, where the water branches in two directions, is located in Khanauri, which is where the bodies often turn up.

Malik grew up alongside the canal in the state of Haryana. He was 12 when he discovered his skill for diving.

“A woman was washing her clothes at the canal when she lost her balance,” the bearded Malik recalled. “She cried for help and I jumped in as others watched on. I saved her life and a local newspaper carried the news with my photograph.”

Malik was excited when the police officer in charge rewarded him for his bravery with 50 rupees, less than $1 in today’s money.

“That was five months’ rent in 1991-92,” he said with a smile. “My father was a poor man. He could not believe it. He thought I had stolen something.”

A few weeks later, the officer summoned Malik again and offered him 80 rupees to fish out a body. The young boy was scared; the corpse was bloated and decomposed.

“But I dived in, tied a rope around its leg and completed the job,” he said.

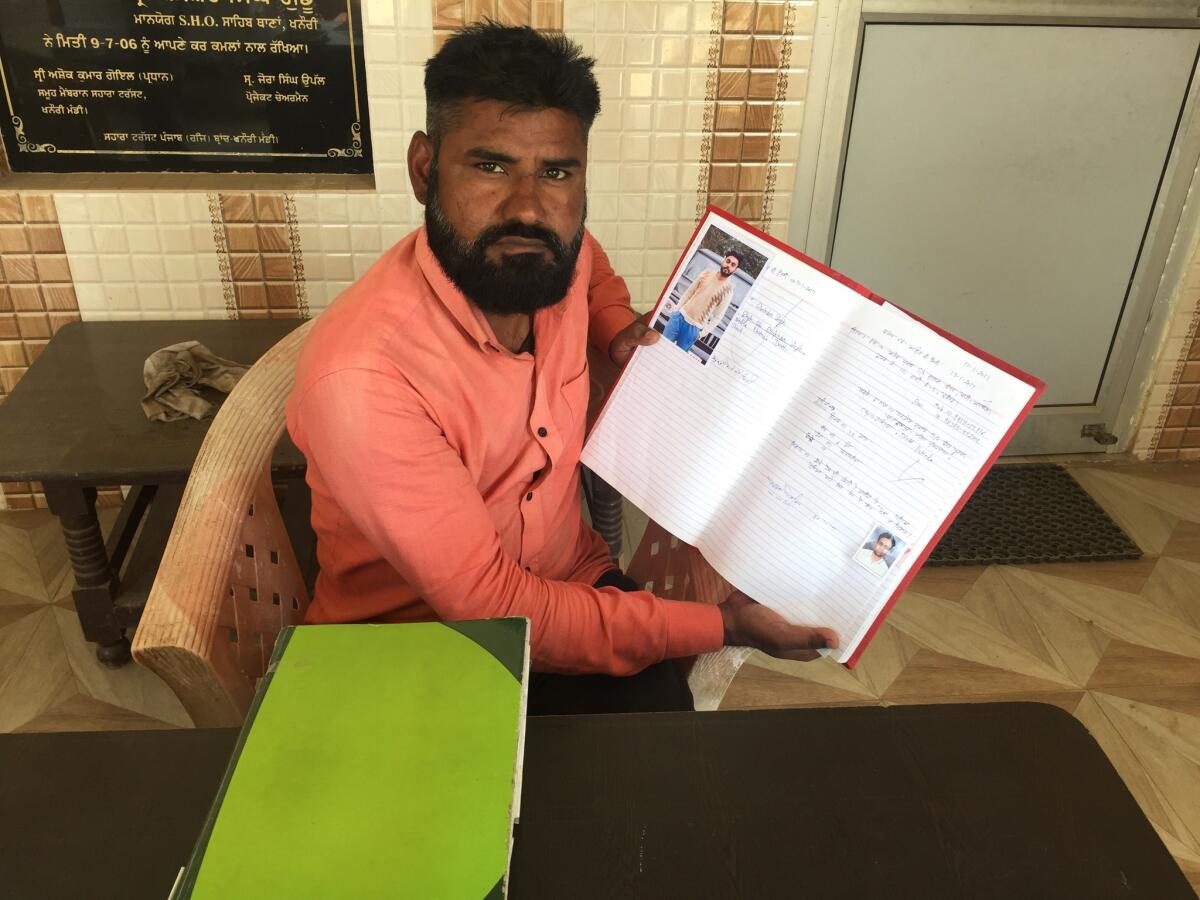

By 1998, Malik was the leader of a team with four divers. He now works with 140 volunteers across four states, all men, and offers their services via a website. He and his team have fished out tens of thousands of bodies, he said, including instances when buses have crashed into the canal with dozens of passengers aboard. He opened a ledger where he has meticulously listed victims by name and date, as well as hundreds of local newspaper clippings.

Malik’s village of Khanauri is in the agrarian state of Punjab, which has a population of just under 28 million. With a farm crisis, drug use and unemployment weighing on people, Malik said suicides are on the rise. His team finds roughly 10 bodies every day, he said, most of them suicides.

So many family members of missing people visit Khanauri in search of closure that, about a decade ago, a local charity built a guesthouse. A full-time police officer sits there now to gather the details of every new missing persons case and circulate them by WhatsApp to Malik’s team.

Based on the location, divers are identified. They strip down to their underwear and swim without any protective gear.

For all his fame, however, Malik lives in poverty. As a child he neglected his studies to focus on diving, because the money he made helped his father, a widower, support him and his three sisters. Malik lives at the guesthouse, paying about $50 in rent a month.

He wishes that authorities would hire him and pay him a fixed salary. He has a robust folder of bravery citations, but no money to pay for the education of his four children, ages 3 to 13. His wife died of cancer two years ago.

His only income comes from families who ask him to recover bodies, but most are debt-ridden — often the reason the person committed suicide in the first place. It costs about $200 to deploy divers across many parts of the canal, he said. But if a family is poor, he won’t ask for money.

“I am happy with their blessings,” he said.

Sometimes he finds valuables that were dropped into the canal, pawning them to raise about $100 every month. Occasionally, police officials have accused him of stealing items off the bodies. Malik denies this, believing the police resent him because by finding bodies, he exposes the incompetence of the authorities.

“I have been interrogated several times,” he said bitterly. “But they have not found anything against me. Villagers have always stood by me.”

“I believe I have been helpful and honest while doing what I am doing,” he went on. “But it is not enough to ensure an education for my kids. Am I asking for too much?”

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Parth M.N. is a special correspondent.

ALSO:

Another Dalit suicide on campus raises fears of a crisis of discrimination at Indian universities

The elaborate ceremony that says everything you need to know about India-Pakistan tensions

Bone by bone, Iraqis unearth a mass grave: ‘We will be out there digging until no one is left’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.