Russia’s meddling in other nations’ elections is nothing new. Just ask the Europeans

- Share via

Russia’s suspected interference in last year’s U.S. presidential election may have come as a surprise to some. But to many European nations, such an intrusion is nothing new.

For years, Russia has used a grab bag of illicit tactics, including the hacking of emails and mobile phones, the dissemination of fake news and character assassination, to try to undermine the political process in other countries.

“They have a history of doing this,” Roy Godson, professor of government emeritus at Georgetown University, told a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing Thursday. “They find this a successful use of their resources.”

Moscow has recently stepped up this type of activity, targeting political processes in France, Germany and the Netherlands, among other nations, according to experts who testified on the first day of a series of Senate hearings on Russia’s propaganda and intelligence campaign aimed at undermining the 2016 vote.

Russia’s tentacles are far-reaching in Europe

Some of the nations Russia has stung are Western foes, others former Soviet republics, or states that fall within Moscow’s sphere of influence.

“There are ample examples,” Eugene Rumer, director of the Russia and Eurasia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told the Senate committee.

Ukraine was hit during its 2004 and 2014 election campaigns, Rumer said. Malware was used to infect the servers at Ukraine’s central election commission and was also believed to have been responsible for a December 2015 power outage that left thousands of Ukrainians in the dark, according to media reports.

Hungary, the Baltic States, and the former Soviet republic of Georgia, which Russia invaded in 2008, have also been the target of political subversion by the Kremlin, which has often sought to bolster the political ambitions of far-right and Euro-skeptic parties or foster instability or social unrest, experts said.

“It is really in central and Eastern Europe that they’ve really been able to practice and hone these techniques and you’re now starting to see that they’re comfortable enough with them to start to export them to other parts of the world,” Hannah Thoburn, a research fellow at the Hudson Institute, said during a conference call about Russia’s interference in foreign elections hosted by the Foreign Policy Initiative, a Washington-based think tank, during the U.S. election campaign.

On Wednesday, Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Richard Burr warned Russia was “actively involved” in efforts to interfere in the upcoming French and German elections.

“We’re on the brink of potentially having two European countries where Russia is the balance disruptor of their leadership,” Burr said at a news conference. “A very overt effort, as well as covert in Germany and France, already been tried in Montenegro and the Netherlands.”

The first round of the French vote is set for April. If no candidate wins a majority, a runoff election between the top two candidates will be held in May.

Experts said Russia’s aim was to support France’s far-right candidate Marine Le Pen, whose National Front party received an $11.7-million loan from a Russian bank in 2014, according to several international news reports. Russia has also reportedly lent money to Greece’s Golden Dawn, Italy’s Northern League, Hungary’s Jobbik and the Freedom Party of Austria — all far-right nationalist parties.

Putin has denied meddling in France’s politics and has called accusations of Moscow’s interference in the U.S. election “lies.”

The Kremlin’s political favorites in other European nations — typically populists — have been given favorable news coverage by Russian news outlets, such as the state-owned satellite network RT and the website Sputnik, while their opponents are denigrated, often in fake news stories and by Internet trolls, experts said.

In December, the English-language Moscow Times newspaper reported that RT was given an additional $19 million to start a French-language channel.

Germany is also believed to have fallen prey to Russian attempts to undermine the country’s presidential election, scheduled for September. The country’s domestic intelligence agency has accused Russia of cyberattacks and cyberspying, according to a report in November by the Associated Press.

Bruno Kahl, who heads Germany’s Federal Intelligence Service, said material hacked from the German parliament and published by the whistle-blower website WikiLeaks came from the same Russian group that hacked the U.S. Democratic National Committee, the AP reported.

“The perpetrators have an interest in delegitimizing the democratic process as such — whomever that later helps,” Kahl was quoted as saying.

America’s hands are not clean

The U.S. has a long history of trying to influence presidential elections in other countries and did so as many as 81 times from 1946 to 2000, according to a database amassed by political scientist Dov Levin of Carnegie Mellon University.

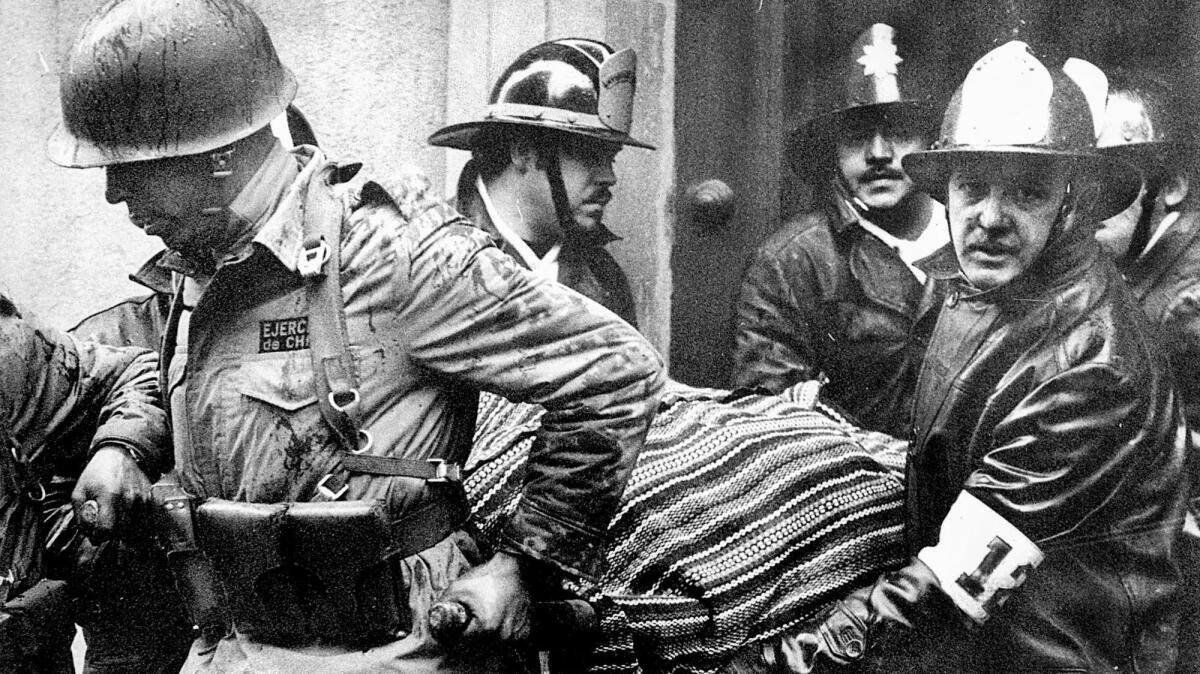

That number does not include military coups and efforts to change a regime following the election of candidates whom Washington considered unfavorable — notably in Iran, Guatemala and Chile. Nor does the number of cases include general assistance the U.S. has provided during an electoral process, such as election monitoring.

During the Cold War, the goal of U.S. meddling was primarily to contain the spread of communism, and the approach continued into the post-Soviet era, stretching from the Middle East and Europe to Latin America and the Caribbean, according to Levin’s research.

Examples include the spreading of negative news against Marxist Sandinistas in Nicaragua in 1990, resulting in the presidential election defeat of Daniel Ortega; training and financial support given to Vaclav Havel’s party and its Slovak affiliate in the former Czechoslovakia; and supporting particular candidates in Haiti in an attempt to weaken the presidential prospects of Jean-Bertrande Aristide, a Roman Catholic priest and proponent of liberation theology.

And as Moscow likes to point out, Washington has also tried to sway Russian elections. In 1996, for example, the White House endorsed a $10.2-billion International Monetary Fund loan to help shore up the floundering Russian economy and allow then-President Boris Yeltsin to gain popularity while spinning the narrative that only he had the reformist credentials to secure such loans.

Times staff writer Nina Agrawal contributed to this report.

For more on global development news, see our Global Development Watch page, and follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

ALSO

Putin: ‘Read my lips,’ there was no Russian meddling in U.S. vote

One of the biggest breakups in history gets underway as Britain files to leave European Union

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.