After Ukraine election, turmoil continues in east

- Share via

Reporting from KIEV, Ukraine — Petro Poroshenko has yet to be declared winner of Ukraine’s presidential election, but the challenges facing the presumed new leader were on dauntingly full display Monday.

Pro-Russia gunmen who claim control of nearly 15% of the country invaded the international airport in Donetsk after thwarting voter participation in the election Sunday to choose a head of state to succeed ousted Kremlin ally Viktor Yanukovich.

Masked militants toting heavy weapons set up positions at the modern glass-and-steel terminal at Donetsk Sergei Prokofiev International Airport, built as the city of a million’s stylish welcome mat for the 2012 European soccer championships.

Ukraine’s interim leaders deployed helicopter gunships and ground reinforcements to regain control of the airport in midafternoon, and a spokesman for the Defense Ministry’s beleaguered “anti-terrorist operation” said government forces had wiped out a gun emplacement of the rebels and secured the runway, control tower and access to the facility.

Still, the airport remained closed to commercial flights for safety reasons and was apparently destined for the kind of armed standoff that persists in a dozen towns and cities of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Poroshenko, the 48-year-old billionaire who has been a player in two previous Ukrainian governments, compared the pro-Russia militants to Somali pirates — elected by no one and pursuing their own selfish interests. He said the government in Kiev would never negotiate with terrorists, but he acknowledged that the tense and deadly standoff was unlikely to ease without the involvement of Russian leaders.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov issued an early assurance that the Kremlin was “ready for dialogue” with the presumed winner of the election. Poroshenko has production and marketing interests in Russia, and Russian President Vladimir Putin has intimated that he could do business with him.

But Lavrov’s tentative olive branch was offered with the warning that Kiev must cease its military campaign to retake control of the militant-occupied areas in Ukraine’s east.

“We cannot turn a blind eye to the fact that the so-called anti-terrorist operation did not end,” Lavrov said of the Kremlin’s insistence that Sunday’s election couldn’t be considered valid if violence was being waged against the Russian-speaking eastern regions. Failure to halt the operation now that Kiev has new leadership in sight “will be a huge mistake,” he warned.

The attack by Ukrainian air force troops later Monday was likely to anger the Kremlin, which has sought to cast Kiev’s efforts to recover authority in the east as evidence that it is bent on repressing the Russian-speaking minority in the Donbass region, where Soviet-era industrial integration remains.

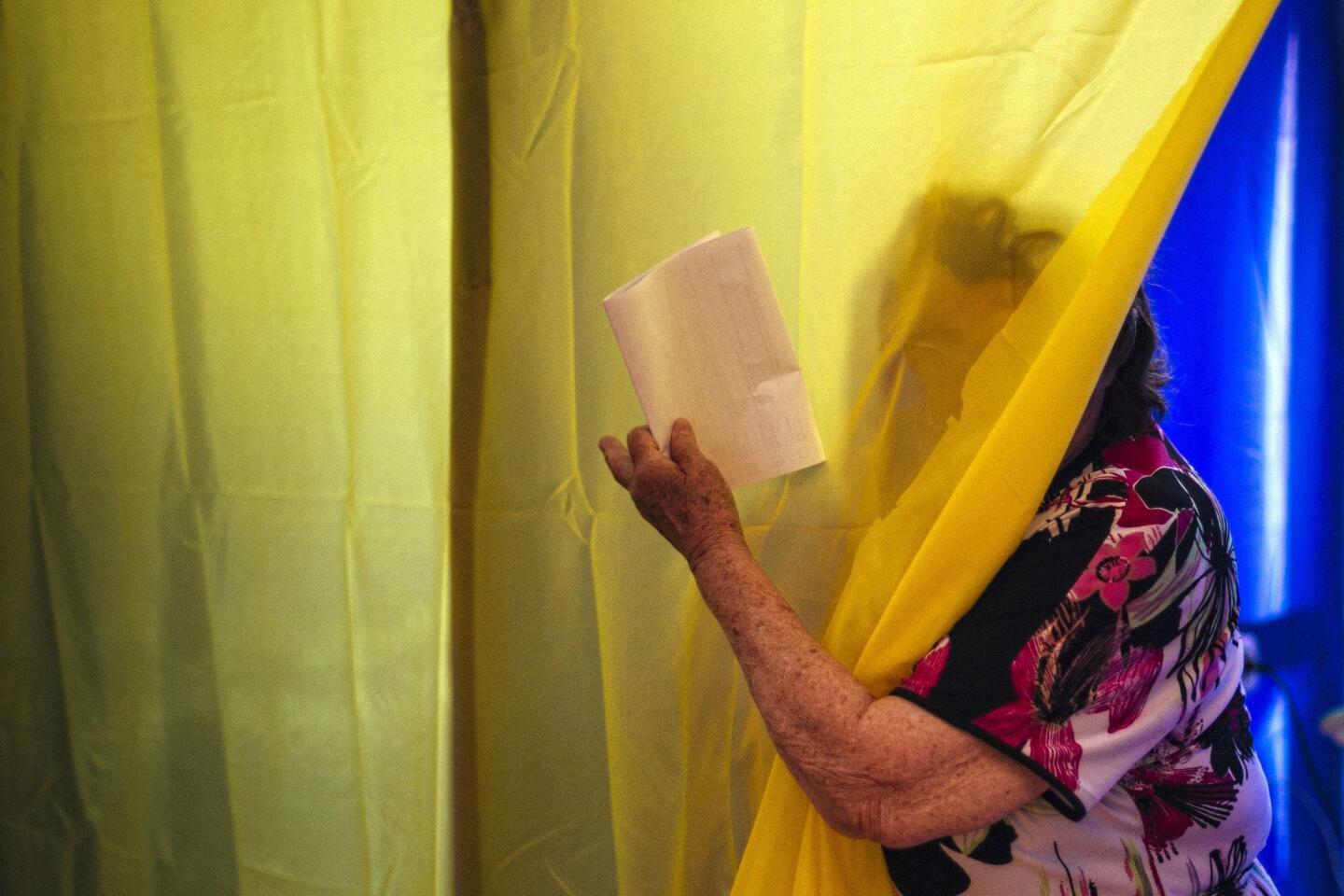

International affairs experts who were in Ukraine to observe the election portrayed the vote as an inspiring triumph of civic spirit and commitment to democracy over the nationalist aggression driving the separatists in the east.

“The majority of the country was able to vote in a most orderly and disciplined way and made their voice absolutely clear,” said former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, head of the National Democratic Institute, which sent dozens of observers to oversee the voting.

Sidestepping a question about whether stricter sanctions against Moscow were in order for its alleged backing of the militants who prevented Donetsk and Luhansk voters from casting ballots, Albright said it was “important to focus on the main story here, that the way people voted made clear they want a moral country.”

Jane Harman, the longtime California congresswoman who now heads the Wilson Center think tank in Washington, said it was time for some “tough love” for Ukraine, which has squandered previous opportunities to build a country committed to democracy and the rule of law.

Noting that the public fervor for change was betrayed after the country proclaimed its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and again when the 2004 Orange Revolution deteriorated into strangling corruption, Harman said Poroshenko’s mandate to create a new Ukraine might be the last chance for the country to seize the opportunity for reform with Western assistance.

“It’s either third time’s the charm or three strikes and you’re out,” said Harman, a Los Angeles Democrat.

Asked how the outbreak of Russian nationalist aggression in eastern Ukraine could be reversed, she said Poroshenko and his incoming team of leaders were obliged to set the country on a clear course for economic recovery, which would be the envy of those now aligned with Russia, which has been hit by Western sanctions for its seizure of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula and its attempts to wrest Luhansk and Donetsk from Ukraine.

Whether Putin’s recent conciliatory statements about working with Ukraine’s newly elected leader are to be trusted, Harman balked at the idea that the Kremlin is controlling Ukraine’s future.

“The conversation should be about Ukraine, not about Putin,” she said, expressing the hope that Poroshenko can build an inclusive government to address the Russian-speaking minority’s concerns while honoring the mandate given him by Ukrainian voters fed up with life in a dysfunctional state nearly a quarter of a century after independence.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.