Journalists are fleeing for their lives in Mexico. There are few havens

Mexico is now the most dangerous country in the world for journalists. (Feb. 5, 2018)

- Share via

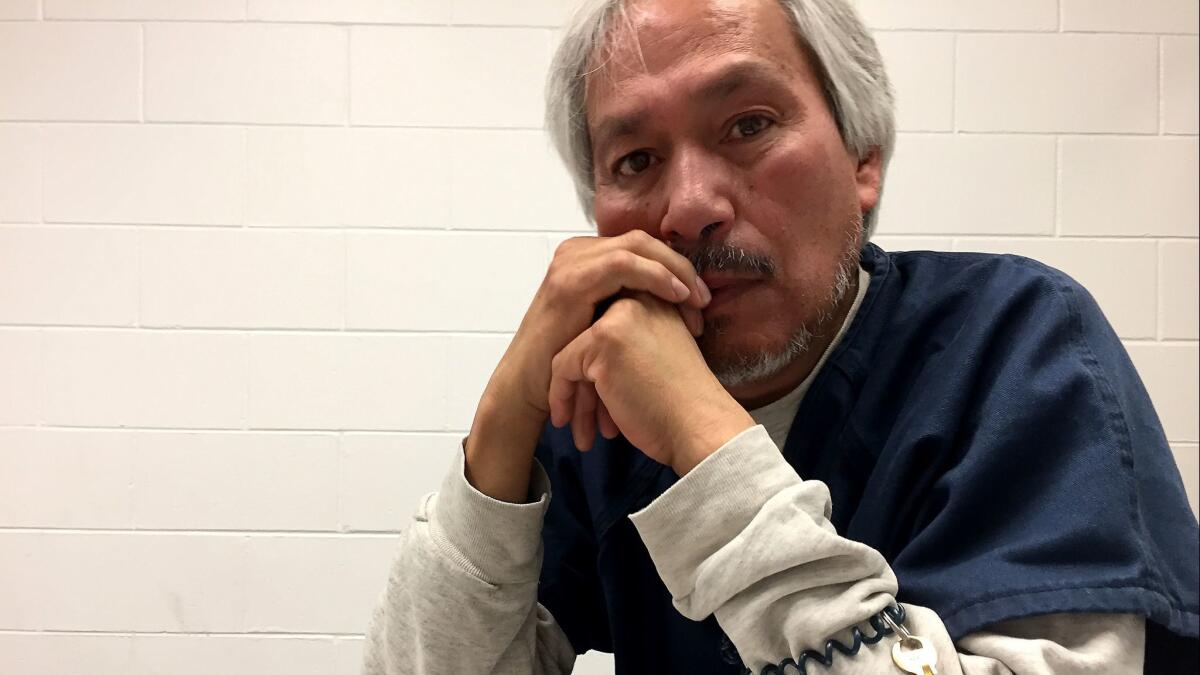

Reporting from EL PASO — During sleepless nights in an immigrant detention center in Texas just north of the border, Emilio Gutierrez Soto has had a lot of time to think. Shivering on a flimsy mattress under thin sheets, 54-year-old Gutierrez finds himself circling back to the same question: Was it worth it?

Was it worth writing those articles critical of the Mexican military? Was it worth having to flee Mexico after receiving threats against his life?

Many miles away, in a teeming Mexican metropolis, Julio Omar Gomez is not confined behind bars, but might as well be.

Since last spring, Gomez, 37, has been living under state protection in a cramped, anonymous apartment many miles from home. He typically only leaves for appointments with his psychologist, who is treating him for anxiety and post-traumatic stress.

Gomez, too, wonders whether his journalism was worth it. Was exposing government corruption in his home state of Baja California Sur worth the three attacks on his life? Was it worth having to send his children into hiding?

Last year, reporters and photographers turned up dead in Mexico at a rate of about one per month, making it the most dangerous country in the world for journalists after war-torn Syria. They were some of the country’s most fearless investigators and sharp-tongued critics, shot down while shopping, while reclining in a hammock, while driving children to school. In January, 77-year-old opinion columnist Carlos Dominguez was waiting at a traffic light with his grandchildren when three men stabbed him 21 times.

Less known are more than two dozen journalists, who, like Gutierrez and Gomez, have given up their work, their homes and their families to save their lives.

There are no good options for Mexican journalists on the run.

Of the roughly 15 or so who fled to other countries in recent years, a majority have sought refuge in the United States, according to press freedom advocates.

Though a few won asylum during the Obama administration, denials or prolonged detention have been the norm under President Trump. That’s despite the fact that the U.S. government has made combating violence against journalists one of its priorities in Mexico, funding press freedom efforts and training about 3,000 media workers in recent years on a variety of topics, including security.

Last May, Mexican journalist Martin Mendez dropped his asylum claim in the U.S. and agreed to be deported after he was held in detention for nearly four months. Gutierrez was denied asylum in November after nearly a decade in the United States. He was about to be deported when the Board of Immigration Appeals agreed to reconsider his case in December. Gutierrez, who has shaggy gray hair and a serious demeanor, is certain he will be killed if he is sent home.

“They want to turn me over to the same government that wants me dead,” he said in an interview inside the sprawling immigrant detention center in El Paso. “I’m just looking for a place to find peace.”

Journalists who go into hiding in Mexico also face an uncertain future. In 2012, two crime photographers who had fled the violent state of Veracruz after receiving threats were found dead, their bodies dismembered.

That year, Mexico established the Mechanism to Protect Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, a program that provides reporters and photographers who have been threatened or attacked with security guards and a panic button that summons authorities. At least 368 journalists have sought these protections over the last five years, although at least one of them was killed anyway.

Mexican officials won’t say how many journalists are living in government safe houses, but press freedom advocates put the number at 16.

The journalists can’t stay forever. Gomez has about six months left under protection. He feels helpless when he thinks about what will come next. “I am broken,” he said at a cafe recently, tears welling behind his glasses. “I am without a future.”

Just a few years ago, his future seemed so bright. The son of an engineer in La Paz, a few hours from the resorts of Los Cabos, Gomez ran a popular news website. He chronicled an explosion of violence in the region, often filming at grisly murder scenes, but his favorite stories highlighted government malfeasance.

In 2016, he told of a La Paz man whose money had been taken by police, who detained him because they said he appeared drugged. The man was not drugged; he was mentally disabled. Gomez drew attention to the case, and eventually forced the police to apologize to the man and return most of his money. Stories like that endeared him to his web audience, but he thinks they earned him enemies in the government.

His mentor, veteran La Paz journalist Maximino Rodriguez, once explained the rules of reporting in Mexico. Drug dealers will offer you money for favorable coverage, Rodriguez said. Never take it. He didn’t warn Gomez that sometimes writing about the government could be most dangerous of all.

Assassins tried to kill Gomez three times. He’s still not sure who they were, but believes they may have attacked him at the behest of the local government. Officials in La Paz did not respond to requests for comment.

The first two times, they set fire to vehicles parked in a downstairs garage at his house. The fires caused major damage to the home and Gomez lost two trucks, but he and his wife and children survived. A crudely lettered note left at the scene the second time warned: “Don’t involve yourself in politics.”

After the second fire, the protection program for journalists implored Gomez to accept 24-hour bodyguards. Gomez was distrustful at first. After all, he thought it was the government trying to kill him.

But last April his mentor, Rodriguez, was gunned down after parking his van in a La Paz parking lot while he was assisting his disabled wife. Distraught, Gomez decided to accept the protection, and soon a team of ex-marines followed him like a shadow.

One night at home, Gomez woke to the sound of gunshots. One of his guards had exchanged fire with two assailants, and lay wounded. That night, the injured guard died. The next day, Gomez and his wife sent their children into hiding and boarded a flight to a city far away.

People don’t typically flee for their lives with a lot of planning. It’s a decision typically born in a moment of panic. Gutierrez made his choice in 2008, shortly before his 45th birthday, after he says a friend warned him that the army was out to kill him.

“You’ve got to leave now,” said the tearful friend, a woman who was dating a soldier.

Gutierrez says he had first received threats three years earlier, after he published stories accusing soldiers of raiding a boarding house for migrants and stealing their money.

The military, deployed more than a decade ago to fight drug cartels in the streets, has been accused of much worse. Between January 2012 and August 2016, the National Human Rights Commission received 5,541 complaints of human rights violations by the armed forces, including allegations of rape and murder.

Still, calling out the military publicly was an enormous risk. Several days after publishing his stories on the boarding house raid in 2005, Gutierrez said, he was summoned to meet with several military leaders.

“You’ve written three idiotic stories,” Gutierrez said a general warned him. “There will not be a fourth.”

In the following years, Gutierrez said, his home was once ransacked by dozens of soldiers, who said they were searching for drugs. Another time, patrols of soldiers drove slowly back and forth in front of his house.

A few days after the warning from his friend, Gutierrez got in a car with his 15-year-old son, whom he was raising alone, and drove north through the vast Chihuahua desert. At the border, he asked an immigration agent for political asylum.

“We’re not afraid,” he told the agent. “We’re terrified.”

With his dramatic story, Gutierrez thought he would easily win protection in the U.S. He was wrong.

Only a few hundred Mexicans receive asylum each year — many fewer than people from countries including India, Ethiopia and China.

Lucas Guttentag, who served as a senior advisor at the Department of Homeland Security under President Obama and now teaches law at Stanford University, says he worries that denial rates are high because judges fear that lenient decisions could fuel more migration from Mexico.

“There’s a reluctance, an aversion even to recognizing an asylum claim from Mexico,” he said. “I worry that it is unduly influenced by enforcement concerns rather than humanitarian concerns.”

Gutierrez and his son spent months in detention before being released on parole. In the intervening years, Gutierrez moved to Las Cruces, N.M., and worked as a gardener, a cook and food truck operator, slathering cheese and mayonnaise on cobs of corn. It wasn’t journalism, but he felt safe.

Last year, Gutierrez was honored in Washington with the National Press Club’s prestigious Press Freedom Award. Shortly after, Gutierrez and his son were detained. His asylum denial has provoked outrage among many U.S. journalists and migrant advocates, who have organized protests outside the detention center where he and his son are being held.

Deep inside a labyrinth of cold concrete corridors, Gutierrez can’t hear the protests. He rarely sees the sun. He wishes he had chosen another career. Farming, maybe. Or masonry, like his father. Every week in detention, he says, he feels a little less alive.

“I feel like I’m another dead journalist,” he said.

To read this article in Spanish, click here

Twitter: @katelinthicum

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.