Hundreds of Central Americans in caravan cross into Mexico

Nearly 1,000 Central American migrants from a U.S.-bound caravan crossed illegally into southern Mexico on Saturday, vowing to continue their controversial journey north.

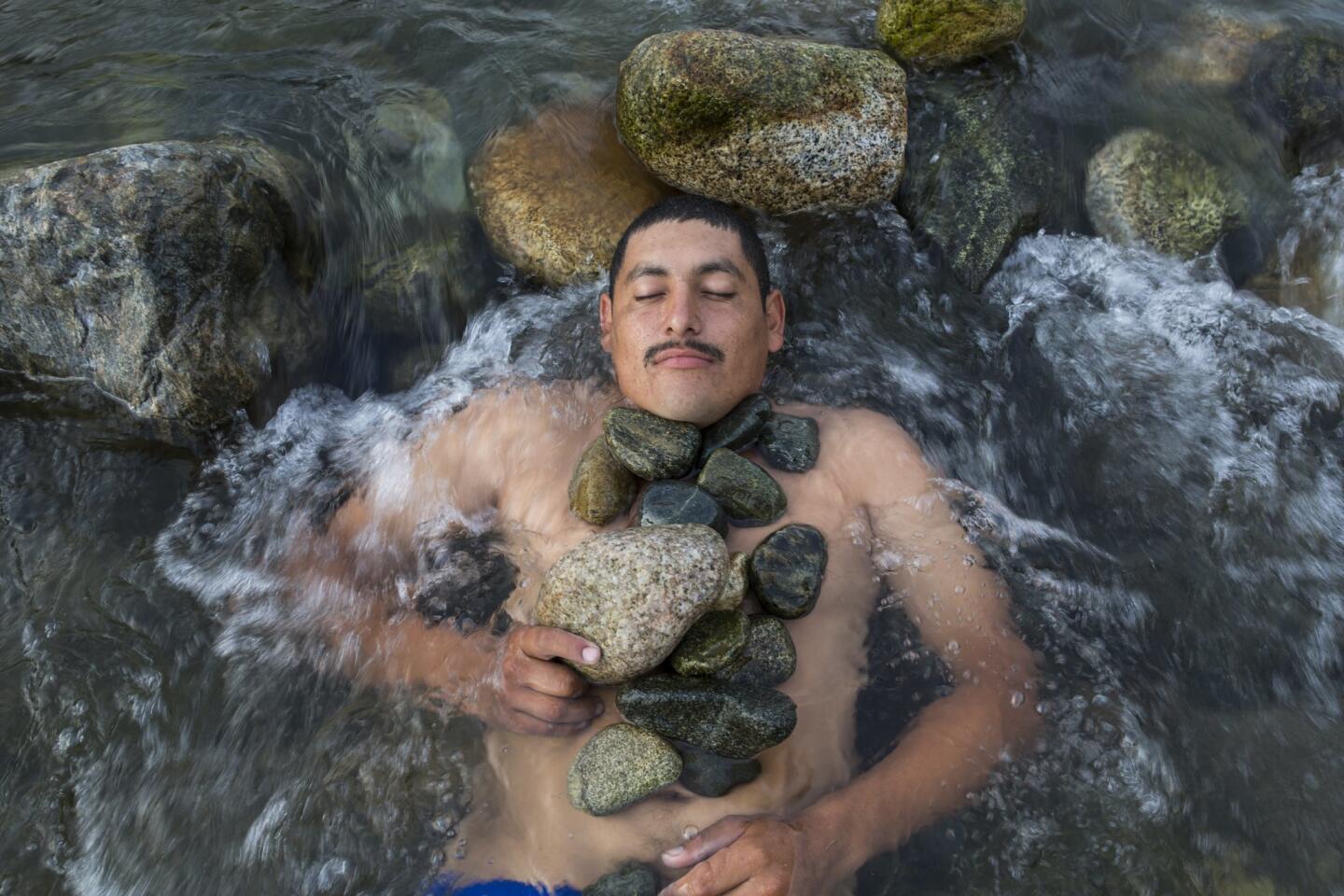

The migrants, most of them from impoverished and violence-plagued Honduras, crossed the Suchiate River — which defines the border between Guatemala and Mexico — after the caravan was denied entry at an official Mexican border crossing Friday. Some migrants swam across the river, their possessions wrapped in plastic garbage bags, while others boarded rafts or waded through the fast-moving water with the assistance of a rope strung from the banks.

Hundreds of Mexican federal police officers and immigration agents did not move to stop the migrants who crossed illegally, despite repeated warnings from Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto in recent days that “irregular” immigration would not be tolerated.

There was a range of estimates of how many people crossed illegally. The federal government said it was roughly 900. Gerardo Hernandez, head of the civil protection agency in the municipality of Suchiate, Chiapas, said it was likely much higher. He said that 7,233 immigrants have been registered in the last three days at a shelter in the border town of Ciudad Hidalgo, and that his agency has been asked to help provide the immigrants with food and shelter.

Hernandez was not sure whether the government planned to try to deport the new arrivals. “We don’t know what’s going to happen,” he said.

The federal government said 2,200 other migrants remained in Guatemala, many of them camped out on the international border bridge that leads to Mexico. Some said they want to seek political asylum in order to stay in Mexico, while others said they were holding out hope that Mexico would open the border and let them continue toward the United States.

“We are hungry; we are thirsty,” said Suami Castillo, 34, as she waited with her toddler son on the bridge, which reeked of urine and rotting trash in the sub-tropical swelter. “We are waiting peacefully. We ask the president of Mexico to open the border for us.”

On Friday, the bridge was the scene of a violent melee that erupted when a larger group of migrants stormed through Guatemalan frontier barricades and tried to force their way into Mexico.

Hundreds of Mexican police in riot gear thwarted that effort to breach the border — an operation that drew praise from President Trump, who has labeled the assemblage of bedraggled migrants a threat to U.S. security and vowed to call out the military should the migrants make it to the U.S.-Mexico boundary.

On Saturday, Trump said he was grateful to Mexico for stopping the caravan, speculating that the country’s strong response was “because they respect the leader of the United States.”

But as he spoke, immigrants were streaming illegally into Mexico — and officials were not trying to stop them.

As the day went on, many more Hondurans began to leave the bridge and sought to enter Mexico via rafts from the Guatemalan side.

By the afternoon, hundreds of immigrants who had crossed the river illegally were celebrating in a plaza in the Mexican border town of Ciudad Hidalgo, dancing to the music of a live marimba band. Each time a group of newly arrived migrants entered the plaza, they were greeted with chants of “Yes, you did it!”

Mexican immigration agents occasionally circled the plaza in vans and dozens of federal police patrolled on foot, but none of them moved to detain the immigrants.

The migrants have been joined by activists from Pueblos Sin Fronteras, an immigrant advocacy group that organized a caravan of Central Americans earlier this spring that drew the ire of President Trump and prompted him to send National Guard troops to the border.

Jose Sorto, a member of the group, said his organization did not organize this caravan, which was launched about a week ago in the Honduran city of San Pedro Sula. He said about two dozen volunteers with the group decided to come help the migrants transit through Mexico. He said he helped about 450 immigrants cross the river Saturday, and said the caravan planned to start its journey north in the next day or two.

Just what will happen to the caravan remains to be seen.

Mexican immigration checkpoints line the roads from the Guatemalan border and Mexican authorities have aggressively sought out, arrested and deported tens of thousands of undocumented Central Americans in recent years.

Members of the caravan hope that by traveling together in a large group, they will be less vulnerable to immigration authorities. Members of the large caravan that departed this spring were given transit visas that allowed them to pass through Mexico to reach the United States.

In recent days, as President Trump has warned of dire consequences for Mexico and Central American nations if the caravan is not stopped, Peña Nieto insisted that his country would not allow the migrants to enter en masse, and that only those with visas or valid refugee claims would be allowed to enter. Their cases will be reviewed one by one, he said, a process that can drag on for weeks.

“Like any sovereign nation … Mexico will not permit irregular entry into its territory — and much less in a violent manner,” Peña Nieto said Friday in a stern national address. “Mexico remains ready to help migrants who decide to enter our country respecting our laws.”

Mexican immigration officials did let some people pass through the border checkpoint. Officials said they had received 640 applications from Hondurans seeking refugee status in Mexico. Among them were 164 women, some of them pregnant, and 104 children, some as young as 3 months old. Officials gave no indication of the status of the requests. But applicants for refugee status in Mexico are generally granted temporary residence until their applications are processed, which can take months.

The caravan has posed a significant dilemma for Mexican authorities, pitting the country’s crucial relations with Washington against its asserted respect for human rights and compassion for migrants. Mexican authorities routinely assail what they call the Trump administration’s xenophobic rhetoric about Mexican immigrants in the United States and its insistence that Mexico pay for a wall along the U.S. border to keep them out.

But Mexico and Central American nations have come under intense pressure to halt the caravan from Trump, who has repeatedly highlighted the 3,000-strong caravan during campaign rallies in advance of next month’s U.S. midterm election.

“They’re not coming into this country: They may as well turn back,” Trump said Friday in Arizona. “As of this moment, I thank Mexico. If that doesn’t work out, we’re calling up the military, not the National Guard.”

The presidents of Honduras and Guatemala — both heavily dependent on U.S. support — met Saturday in the Guatemalan capital and were working on a plan to take Honduran migrants not allowed into Mexico back to their homeland.

At least 10 buses filled with Honduran migrants had already left the Guatemalan border town of Tecun Uman, ferrying discouraged migrants back home.

“They’re not going to let us pass,” said a dejected Julissa Hernandez, 16, who was aboard a small bus heading back toward Honduras from Guatemala. “It has been so hard.”

Like others, she said she had left Honduras in search of work in the United States. But she concluded that it wasn’t worth risking her life and opted to go home.

Others, however, remained intent on continuing their journey, despite what they perceived as Mexico’s hard line, because of the lack of opportunity and rampant crime in Honduras.

“You can’t study, you can’t leave your house without fear that they will kill you,” said Johana Flores, 16, who was resting in a park on the Guatemalan side. “I am afraid. If I go home, I will die of hunger or be killed by the gangs.”

The Trump administration has characterized most U.S.-bound Central Americans as economic migrants who have no legal standing to enter the United States. Washington has generally rejected fear of criminal violence as a basis for political asylum, and has repeatedly linked Central American migrants to violent gangs such as MS-13.

“You got some bad people in those groups,” Trump said Friday at the Arizona rally. “And I’ll tell you what, this country doesn’t want them.”

On the border bridge, where hundreds lined up behind a tall, white steel gate that marked the Mexican side, the situation remained tense, amid scenes of desperation.

Red-eyed mothers and fathers cradled crying infants. Children drenched in sweat toted luggage.

“Look at these kids without diapers, without food,” said Eva Fernandez, a U.S. citizen and California resident who heads an immigrant advocacy group, as she livestreamed the scene to friends in Honduras. “We are suffering.”

Mexican immigration officials handed out cups of water through the border fence.

--Staff Writer Linthicum reported from Ciudad Hidalgo and McDonnell from Mexico City. Cecilia Sanchez in the Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed.

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

UPDATES:

8:05 p.m.: This story has been updated with additional details and background.

This story was originally published at 1:55 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.