In Cuba, home of future U.S. Embassy has stories to tell

Reporting from Havana — “Fatherland or death” might seem an unusual motto for a banner hanging outside a United States diplomatic post.

But on a plaza across from the clunky six-story building that serves such a purpose in Havana, the words — placed by Cuban foes — stand larger than life, along with the proclamation Venceremos! We will triumph.

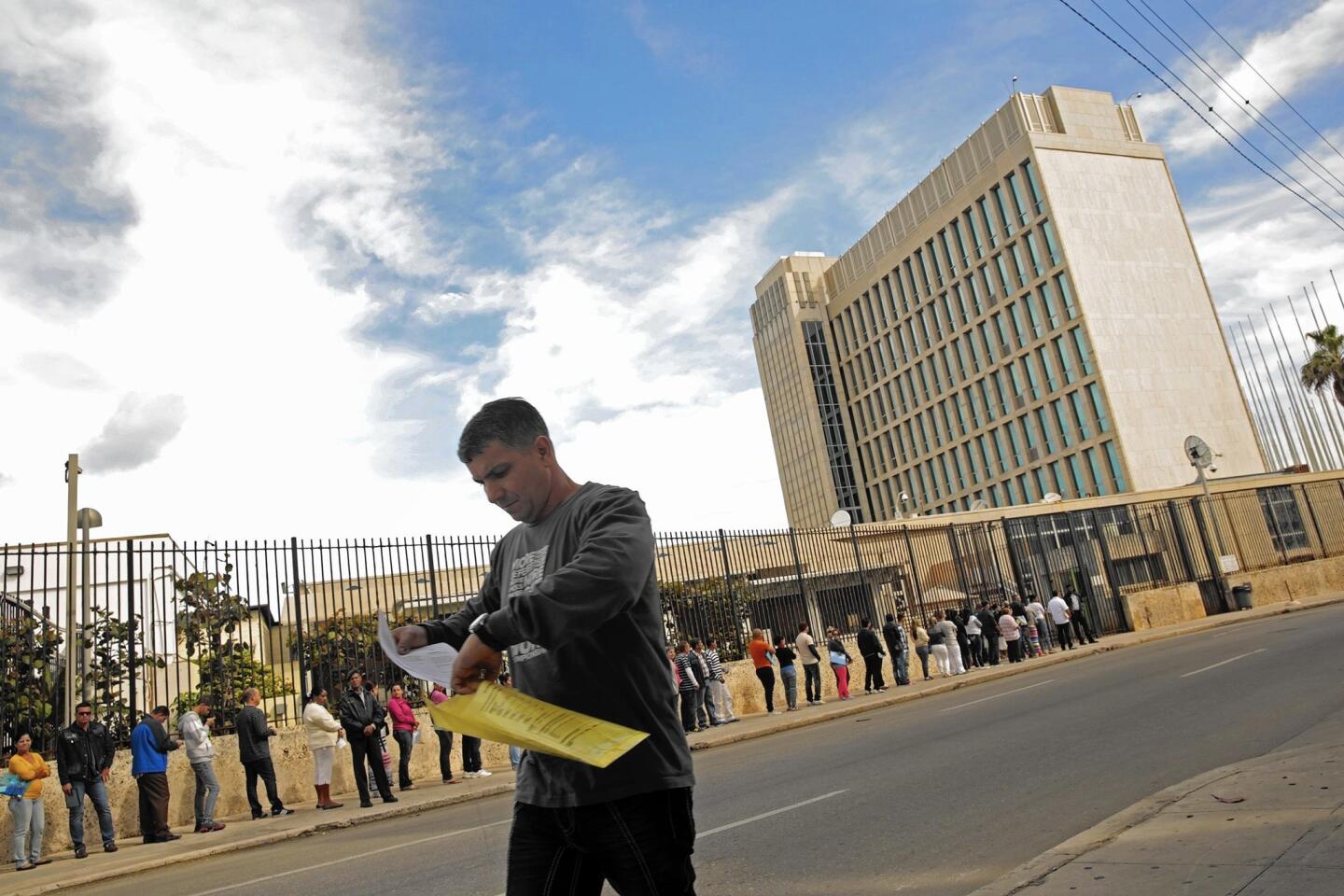

It is here that American diplomats are expected to soon open a new embassy, the first tangible symbol in the reestablishment of formal ties between Cuba and the United States after more than half a century of formal hostility and estrangement.

The history of the building — the U.S. Interests Section — and the people who have worked in it over the years tell the story of the foibles of U.S.-Cuban relations, a kind of vacillating status of formal Cold War foes who at times have shared private chats, mojitos and barbecues.

Suspicious Cuban authorities often regarded the interests section, with some justification, as a hotbed of espionage and hatched-up plots to support dissidents and undermine the government of President Fidel Castro.

For the Americans, the mission on Havana’s Malecon, or seafront boulevard, has served as an important listening post, from which envoys could keep tabs on what was happening on the island and speak to ordinary Cubans, although if those citizens approached the building, their names would be registered and they’d probably receive a visit from state security agents.

Serving in Cuba “was like a B-movie,” a frequent “cat-and-mouse game,” said Gary Maybarduk, who was the political-economic officer at the interests section from 1997 to 1999.

“Your first meeting upon arriving, with [U.S. diplomatic] security, is to tell you to expect your home is bugged … and there might be [hidden] video cameras in your bedroom,” Maybarduk said.

“You knew your maid was reporting back to the government,” he said.

In the interests section building, the U.S. was required to employ Cubans, vetted by the Cuban government, for about 80% of the jobs. Given the political sensitivity, Cuban employees were generally not permitted above the third floor.

In 2008, a senior Cuban Foreign Ministry official, Josefina Vidal, publicly accused the head of the U.S. Interests Section at the time, Michael Parmly, of personally bringing money from Miami to dissidents in Havana.

She called it “outrageous and scandalous” that Parmly delivered funds to “terrorists and mercenaries,” the invective that Cuban government officials often use to refer to opposition activists. As evidence, she presented what she said were intercepted emails.

Vidal is now leading the Cuban delegation negotiating the renewal of diplomatic ties. She and Roberta Jacobson, assistant secretary of state, are holding talks Friday at the State Department after a first round of talks last month in Havana.

The building on the Malecon was the U.S. Embassy in Havana until ties were broken in 1961. Ambassadors were recalled, and the Swiss government handled all matters until the U.S. Interests Section was created in the same building in 1977. A Cuban counterpart was opened in Washington.

Travel restrictions remain on diplomats in both cities; neither side can move outside a perimeter of several miles without special permission. This is one of the limits that both countries plan to change once embassies are reestablished.

A Cuban diplomat with a notoriously bad sense of direction tells the story of once traveling away from his interests section in Washington when he thought he was headed toward it, and not realizing the mistake until he nearly reached New Jersey. An international incident was narrowly averted.

Tension usually went up or down in tandem with who was in the White House; the George W. Bush years often saw flare-ups. In 2003, the U.S. expelled 14 Cuban diplomats from the interests section in Washington and the United Nations, accusing them of espionage. (Vidal, also stationed at the time in the Cuban Interests Section, left Washington in solidarity; one of the 14 was her husband.)

A year earlier, Cuba formally had protested what it said was the smuggling of 500 radios to Cuban dissidents so they could listen to the U.S.-produced Radio Marti programs. Among those accused of distributing the contraband was the chief of the mission, Vicki Huddleston.

And yet several former U.S. diplomats who served in Cuba have fond memories.

Wayne Smith, chief of the mission from 1979 to 1982, recalls friendly conversations with Raul Castro; the then-military commander, who succeeded his brother as president, asked him repeatedly why the two countries just couldn’t talk.

“Obviously, there were various issues that kept us apart,” Smith said. “We had two governments with definite disagreements. But I never saw why we couldn’t move ahead and have more reasonable relations.”

Smith, as a young diplomatic officer posted to Havana, helped shut down the embassy in 1961, then was one of the first to return as chief of the diminished mission.

When he left again, Fidel Castro gave him a farewell cookout. The president told Smith he was sorry to see him go. “I’d like to see you come back,” Smith recalled Fidel Castro saying. “I think he meant as ambassador,” Smith said. “But who knows?”

The residence of the chief of the interests section also reflects a time when relations flourished, and today seems an unlikely real estate holding for a nation in conflict with its host country.

Built in the 1950s, several years before the revolution, it is an opulent mansion with chandeliers and marble; the grounds include tennis courts and a pool. It is not uncommon to find Cuban artists and other well-known figures attending cocktail parties at the home. It’s in a neighborhood of gated estates where, as it happens, Fidel Castro also has long had a home.

The interests section in Havana has also served as the focal point of a protracted propaganda war. In 2006, the Americans erected an electronic ticker with 5-foot letters flashing news items plus criticism of the Cuban government and quotations from American leaders over the ages. The idea was to bombard ordinary Cubans with alternative messages.

The Castros were incensed and responded by erecting about 140 flagpoles in front of the building, each adorned with a large black flag, to block the view of the ticker.

As tension ebbed again, the ticker was eventually removed and so were the flags. The poles are still there, a forest of naked metal balusters.

One flag that is also not on display: the Stars and Stripes. The Cuban government does not allow it to be flown. That may be one of the first changes.

Times staff writer David S. Cloud in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.