Saudi Arabia election features female candidates and voters for the first time

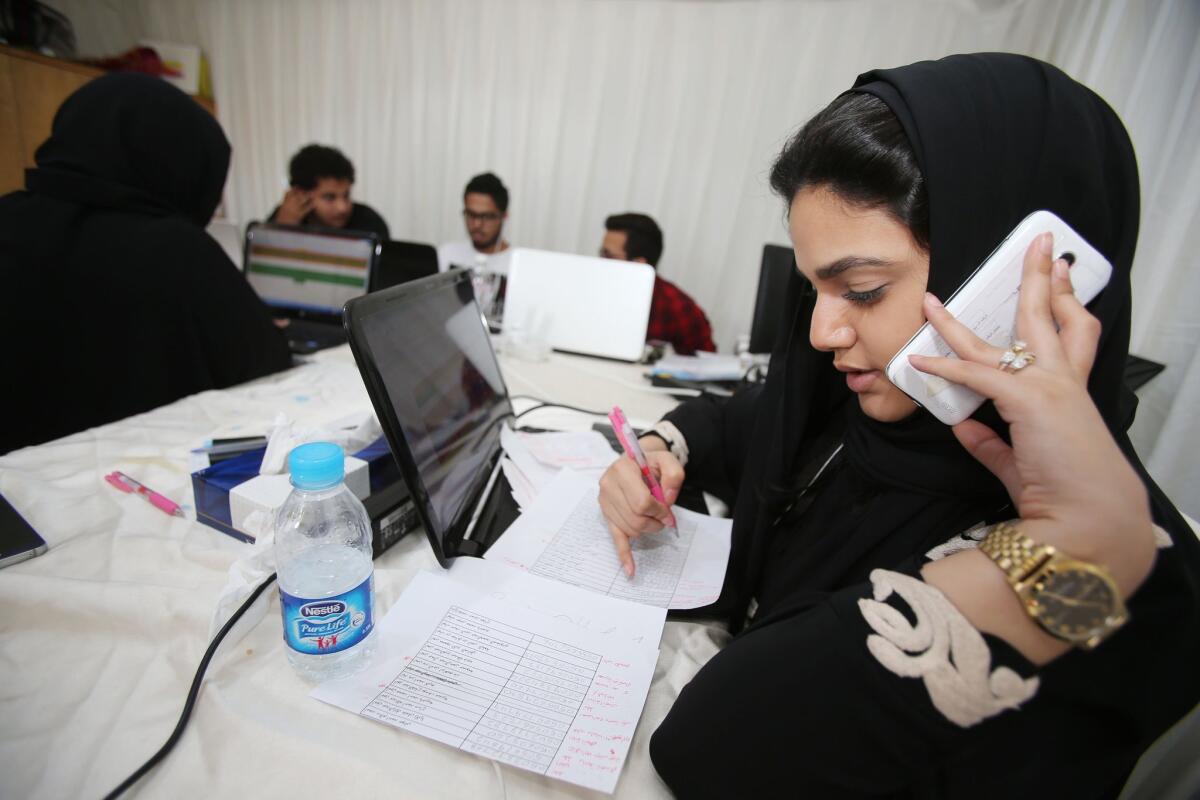

Communication staff members for the campaign of a female candidate in the Saudi municipal elections contact voters in Jidda.

- Share via

Reporting from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia — On a recent night in the Saudi capital, municipal council candidate Amal Badredin Alsnari wooed potential voters with heaping plates of hors d’oeuvres and a pledge to bring more public services to neighborhoods in need.

Looking glamorous in a black head scarf and red pantsuit, Alsnari spoke passionately to about two dozen women gathered in a banquet room at a downtown Riyadh hotel. Next door, in a separate room, men snacked on their own appetizers and listened as Alsnari’s speech played on loudspeakers.

It was politicking, Saudi-style.

As this wealthy desert kingdom prepares for a historic election Saturday, in which women will compete and vote for the first time, Saudi Arabia’s strict gender laws are coloring the political process even as they’re being challenged.

Like all women in Saudi Arabia, Alsnari, 60, a doctor and a grandmother of nine, will not be allowed to drive herself to the polls Saturday.

Even if she wins a spot on the municipal council representing central Riyadh, she will still face scorn by the religious police if she walks the streets alone, and she will still be unable to travel abroad without the permission of a male relative.

According to election rules, female candidates can be fined if they’re caught speaking directly to male voters. Men and women will cast ballots at separate voting centers.

In a country dominated by a strict form of Islam, some clerics have demanded women sit out the elections. Fearing reprisals, many candidates have forgone public campaigning, opting instead to reach out to voters through social media.

With so many restrictions in place, many women view their entry into the democratic process with tempered enthusiasm, even as Saudi officials hail it as a great advancement.

“It’s a good beginning,” said Alsnari’s daughter, Arij Abanomi, 43. “We will see how good.”

Except for Vatican City, where male cardinals elect the pope, Saudi Arabia is the last country in the world to bar women from elections. Women have had the right to vote in other Persian Gulf states for years.

In Saudi Arabia, the seeds of change were planted after the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011, when King Abdullah decreed women should be included in municipal elections.

It was one of several gestures Abdullah made toward female equality before his death in January. He also appointed women to a national advisory body and allowed them to practice law and work as sales clerks in clothing and lingerie shops.

David Ottaway, a Middle East specialist at the Wilson Center, said the kingdom’s slow but steady flow of concessions comes as the demands of pro-democracy activists have largely been silenced.

“They’re not a challenge to the system,” Ottaway said of women activists. “Their issues are women’s rights. They’re not threats to the government.”

The election changes went into effect this year, with nearly 1,000 women joining 7,000 men seeking seats on 284 municipal councils.

Compared with local elected officials in the United States, Saudi council members have little power. They oversee a range of local issues, including budgets for maintaining and improving public facilities, but all major decisions are made by the king and his appointees.

Perhaps because of that, Saudis don’t typically vote in large numbers. Of the estimated 6 million to 7 million Saudis eligible to vote, only 1.5 million are registered.

That number includes 130,000 women who signed up this year, said Salma Rashid, a project manager at the Al-Nahda Philanthropic Society for Women, which led a nationwide voter education campaign. Because women are not allowed to drive in Saudi Arabia, her organization has partnered with Uber to offer women free rides to polling places Saturday.

Rashid said the biggest challenge in registering women was not misogyny but apathy. The most common question from would-be candidates and voters was: What do these councils do?

Some activists have complained that the voter registration process was not well-publicized and was too onerous for women. Registrants were required to prove residency in their district by bringing documents, such as house deeds or bills, that matched their name to their address. But in Saudi Arabia, men own most houses, and men pay most of the bills.

Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch, praised the inclusion of women in the electoral process but said “the government should fix the problems that are making it hard for women to participate.” Whitson said she hoped the elections would “create momentum for further women’s rights reforms.”

That is what Dana Albushi would like to see.

Albushi and her daughter were sharing chicken tenders on a recent afternoon on the women’s-only floor of Riyadh’s soaring Kingdom Center mall, where behind frosted glass barriers women shed the veils and long black robes they are expected to wear in public to take tea and shop at high-end stores such as Chanel, Givenchy and Valentino.

Albushi, 49, said she hopes the election leads to more advancements for women, like the right to drive and travel without a male relative.

“I would like to be able to walk anywhere by myself and just breathe the air,” said Albushi, a former teacher. The election, she said, “is a first step.”

“It’s going to be a long journey, though,” said Nouf, her 14-year-old.

Not all women are embracing their new rights.

Some conservatives have led Twitter campaigns against the elections and other recent changes.

Hatoon Ajward Fassi, a university professor and a leader of the women’s rights campaign known as the Baladi initiative, said there are religious and geopolitical overtones to such resistance. “Feminism is linked to Westernization,” she said. “There’s a lot of baggage around it.”

Nassina Sada, who lives in the country’s Eastern Province, said she believes women’s status as second-class citizens will fade as more Saudis go abroad.

“Nobody can stop the change,” she said.

Sada registered as a candidate but was disqualified by the government. She suspects it has to do with her past activism, including a recent protest in which she posted an online video of herself driving a car.

She said women must continue to press Saudi leaders.

“We need to ask for more,” she said. “I think it is my responsibility for my daughter’s generation.”

MORE WORLD NEWS

Air Force proposes $3-billion plan to vastly expand its drone program

A night of violence that shattered a South African’s view of her white privilege

Brother of San Bernardino killer Tashfeen Malik says family in Saudi Arabia is devastated

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.