The Return of Rocky: A Welcome Sequel : In His 39th Pro Season, Giant Coach Is Just Looking for Place to Spit

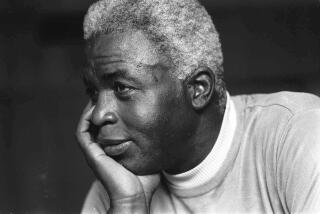

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — Having managed and scouted in the minor leagues for the last 13 years, Everett Lamar (Rocky) Bridges is now back in the majors as a coach with the San Francisco Giants.

“The first thing I did when they said they wanted me back,” Bridges revealed the other day, “was to ask what beer sponsor they had.

“They said, ‘Strohs,’ and I said I’d be happy to come back.”

Time has taken a toll on Bridges’ body, but not his sense of humor.

At 56, his left knee is hobbled by arthritis, forcing him to walk with a bent and painful gait.

The face that resembles Popeye’s, its left cheek bulging with chewing tobacco, appears to represent a weathered reflection of his travels.

“I call him Charles Kuralt,” said Vida Blue, who dresses next to Bridges in the Giants’ clubhouse. “He’s been on the road that long.”

In the spring of his 39th pro season, Rocky Bridges is a survivor, a legacy from another era, a former infielder who spent 11 big league summers delivering more one liners than line drives.

What kind of a career did he have.

“Tainted,” Bridges said. “I probably batted about .250, which wouldn’t be too bad by today’s standards. At least I didn’t have to worry if the writers were going to vote me into the Hall of Fame or not.”

Bridges’ highest salary as a player was $12,500 in 1961. It was his last year as a player and the first year of the Los Angeles Angels, who later moved to Anaheim, which entitled them, of course, to become the California Angels.

“I didn’t need more money,” Bridges said. “It would have been a bad thing. It would have screwed up my checkbook. I couldn’t balance it as it was.”

He went on to spend six seasons as an Angel coach and four as a manager in their farm system.

“The cowboy was a super guy,” he said of Gene Autry, the Angel owner. “I wish he’d adopted me. I told him that once but he didn’t go for it.”

Bridges was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers out of Long Beach Poly High in 1946.

“The Dodgers told me I was the shortstop,” Bridges said. “I was actually about the 33rd shortstop Pee Wee Reese ran out.

“Then I got traded to Cincinnati where Roy McMillan was the shortstop. I had about as much chance as a one legged man in a butt-kicking contest. I stayed with Cincinnati for four years. It took me that long to learn how to spell it.”

Bridges also played for Washington, Detroit, Cleveland and St. Louis before ending his career with the Angels. Did he enjoy his two years with the hapless Senators?

“There was a lot to do and see there,” he said. “It was well worth the trip. But we had so many Cubans that I couldn’t learn the language and so they traded me, too.”

It was while with Washington, however, in 1958 that Bridges was selected to the American League All-Star team.

“Those were the days when every club was represented by at least one player,” he said. “Casey Stengel picked me. He was a pal of mine. I never got in the game but I sat on the bench with Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams and Yogi Berra. I gave ‘em instruction in how to sit.”

Bridges suffered a major setback that year. Detroit’s Frank Lary broke his jaw with a pitch.

“It kept me from making the Hollywood scene,” Bridges said. “I was no longer just a pretty face.”

It was at his first managerial stop in San Jose that Bridges followed a painful loss by saying, “I managed good but they played bad.” The quote was used as the title of a Sports Illustrated article on Bridges and was later used by Jim Bouton as the title for one of his books.

Bridges ultimately managed the Giants’ triple A farm club in Phoenix for nine years.

“We won one pennant,” he said. “The other eight years we showed up.”

When Bridges showed up for his team’s 1975 opener in Albuquerque he told a local reporter, “I don’t know how to spell Albuquerque but I sure can smell it.”

The partisans booed when Bridges was introduced before that night’s game.

He responded by hobbling to the plate, where he did a headstand, turning the boos to cheers.

Bridges laughed, reflecting on his nine summers in Phoenix.

“My friends in Coeur d’Alene (Idaho, where he lives) know why they call me Rocky,” he said. “I spent the winters in Northern Idaho and the summers in a place that’s about one block from Hell. It’s supposed to be the other way around.”

San Francisco changed managers five times while Bridges was in Phoenix. Bridges was never offered the varsity job. Did that disturb him?

“Not really,” he said. “It was not something I’d stop drinking beer over. I mean, some guys got to do it. It’s their big banana. I was just happy being gainfully employed.

“Baseball is the only thing I really know. I lost the Rhodes Scholarship somewhere along the line. You know how the mail is.”

Bridges spent half of last year scouting and the other half managing the Giants’ Rookie League team.

The team played its home games in Everett, Wash.

“It was nice of the Giants to send me to a town that was named after me,” Everett Lamar said. “I’d call in my reports and sign off, ‘This is Everett from Everett.’ ”

He paused, reflecting.

“It was a rare experience. I had kids who were used to playing three games a week. Now they were playing seven a week and it meant something. We didn’t give out lettermen’s sweaters.”

Bridges cited two significant changes in his return to the majors.

“The last time I was in the National League was 1957,” he said. “The only park that’s left is Wrigley Field. It certainly wasn’t my line drives hitting the fences that dismantled them.”

Then there’s the synthetic surfaces, a major concern.

“Can I spit tobacco juice?” Bridges wondered aloud. “Tough bleep if they don’t like it.”

Bridges became a year-round chewer when he moved from Long Beach to Couer d’Alene in 1970.

“I can spit anywhere,” Bridges said. “I’ve got 2 1/2 acres. I’d spit on the carpet if my wife didn’t get upset.”

Bridges was asked if he takes advantage of the rural environment to fish and hunt.

“I don’t do any of that stuff,” he said. “I just look at the trees. I once bought a gun and walked for four years without seeing anything. I have bullets that have whiskers on them.”

Bridges said it’s his wife who has thrived in Idaho.

“She’s learned to sew, cook and preserve,” he said. “When we lived in Long Beach she couldn’t even fix a basketball game.”

It was time for the major league coach to go to work as Manager Jim Davenport’s bench assistant.

He was asked quickly how he got the nickname of Rocky.

“It happened in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1948,” he said. “A public address announcer thought Lamar sounded lousy and started calling me Rocky.

“For quite awhile I thought it was because of my build. Then I realized it fit my game.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.