Couple Keep Heritage of Lankershim Alive

One of Francisco and Maria Avila’s most prized possessions is a painting done by their former employer, the late Jack Lankershim, that exemplifies his pioneer family’s love affair with the San Fernando Valley.

In the painting, which hangs in a prominent spot in the couple’s Granada Hills home, cows graze contentedly amid fruit trees and lush, rolling hills. A winding dirt road crosses the tranquil scene. In the background, the mountains rise almost majestically--unobstructed by tall concrete and glass buildings, the clutter of billboards and neon signs or the dirty brown haze of smog.

The setting for the 1908 painting was what is now the corner of Lankershim and Ventura boulevards--near one of two roads that led to the main house on the 60,000-acre ranch that the artist’s grandfather, Isaac Lankershim, bought in 1869. Lankershim paid Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor of California, $115,000 for the property, which included much of the southern Valley.

Maria Avila, 72, said the home’s other road was a half-mile away at what later became the intersection of Lankershim Boulevard and Vineland Avenue.

“It’s quite a contrast between then and now,” she said. “I look at this painting every time I read about the complaints about high-rise buildings, traffic congestion and billboards on Lankershim or Ventura. I wish others could see it. People don’t realize how nice it was back then. And soon there won’t be anybody around to tell them.”

The Avilas, who lived on the Lankershim ranch from 1929 until the last of family’s original property was subdivided in the early 1950s, are dedicated to preserving the Lankershim name and the family’s place in the Valley’s history.

“They were just like family,” Maria Avila said. “I was only 16 when I married Francisco and moved to the ranch. After we’re gone, there won’t be anybody left who knows how things were then.”

Except for Jack Lankershim’s adopted daughter Jacqueline, who has no children and has lived in Europe for more than 40 years, the last of the Lankershims died in 1948. Maria Avila said Isaac Lankershim’s partner in developing his vast Valley holdings was his son-in-law, Isaac Van Nuys, and “the Van Nuyses are all gone, too.”

As caretakers of the Lankershim estate, the Avilas said they lived in one wing of what they call “the big house,” while members of the Lankershim family lived in the other wing. Orchards of walnuts, pears, peaches and other fruits flourished around them.

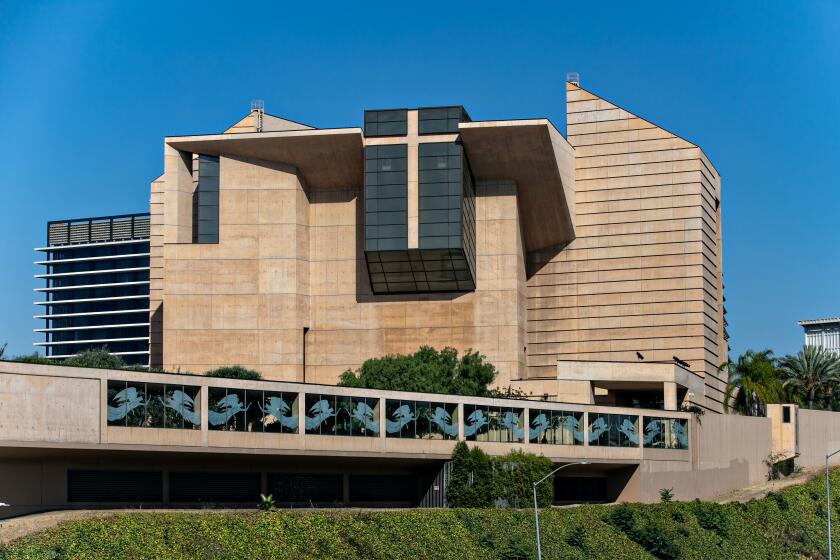

The Avilas’ wing of the house was preserved and moved to Canoga Park. It now is the Chapel in the Canyon, 9012 Topanga Canyon Blvd., Maria Avila said.

The couple inherited many of the Lankershims’ personal possessions. Heavy wooden furniture once used at the ranch, including a four-poster bed, cedar hope chest, treadle sewing machine and huge desk, old pictures and documents, now decorate the Avilas’ home.

A sundial from the Lankershim estate stands in the couple’s backyard. A water pump from the ranch, repainted a shiny red and black, stands in the circular driveway in front of the house. Maria Avila has several pairs of lace pantaloons, handmade in 1903 for the Lankershim women, carefully folded and put away.

Items Donated to Museums

A sword that belonged to Col. J. B. Lankershim, Isaac’s son and Jack’s father, which is on display at Campo de Cahuenga on Lankershim Boulevard in North Hollywood, was donated to the museum by the Avilas. The couple also gave more than 100 items to the Valley College Historical Museum. Francisco Avila is a director of the museum.

In the 1970s, the Avilas successfully opposed North Hollywood merchants when the merchants proposed changing the name of Lankershim Boulevard to Universal Boulevard.

“They changed the name of the town,” Francisco Avila said. “If they had changed the name of the street, there wouldn’t be anything named after the Lankershims left.”

Col. J. B. Lankershim established the town site of Toluca at the eastern edge of the family’s vast holdings in 1888. He later changed the community’s name from Toluca to Lankershim. In 1927, the international lure of Hollywood inspired local merchants to launch a campaign to change the community’s name to North Hollywood. The old town site of Toluca is now part of Toluca Lake.

“They thought they would cash in on the Hollywood image,” Avila said. “They never really did.”

Journal Saved

Among other items saved by the Avilas was a typed and bound journal kept by Col. Lankershim during a 1929 European journey. The journal, entitled “Europe Before the War, Volume 2,” is illustrated with pictures taken by Lankershim during the trip. His writings detail shipboard life among the wealthy and describe places in Europe the Lankershims visited.

The journal also recalls the stock market crash of that year and the attitude of Europeans toward visiting Americans.

“The Swiss innkeepers posted a notice in their hotels that they would charge 20% extra on all bills that were not paid in Swiss money,” Lankershim wrote, “but they afterward rescinded this ridiculous order and practically any American could board at the hotels as long as they wanted without paying until the end of their trip; and soon the hotel companies took any money or checks that they gave them. I had plenty of money with me and paid my bills regularly, being almost the only one that did.”

The second volume of the journal starts in mid-sentence.

“I wish I could have saved the first half,” Francisco Avila said. “It’s such a shame all that was lost.”

Working to Save Monument

The Avilas are working to preserve a stone tower, a little-known monument to Col. Lankershim, in the Hollywood Hills.

The 15-foot-high monument sits behind what was once actor Errol Flynn’s estate, atop a steep, almost inaccessible incline between Mulholland Drive at the end of Nichols Canyon Road. It was built by the Boy Scouts of America more than 40 years ago to honor Lankershim, who had donated several acres of land in the mountains for a campsite.

The Avilas helped convince the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board to declare the stone tower a historical monument in 1977.

Francisco Avila said he at first favored a recent proposal to move the monument to Campo de Cahuenga, where it could be seen by more people. However, he said, after contacting the former Jacqueline Lankershim in Europe, he now opposes the move.

“She said, ‘Frank, don’t let anyone disturb Grandpapa’s monument,’ ” Avila said. “I will honor her wishes. His ashes are scattered there in the mountains. In a sense, it is his burial place.”

Arrived in Toluca in 1920

Francisco Avila first saw his future employer’s vast landholdings in 1920 when he came to Toluca in the eastern Valley from Arizona with his parents. He was 12. At that age, he said, he quit school and went to work doing odd jobs for 20 cents an hour.

“The biggest thrill of my life was to bring that first $10 I earned home to my mother,” he said.

Avila said there was very little in Toluca in those days--”a hotel with some stairs outside, a grocery store, a feed store, not too much else.”

Avila said he later earned 35 cents an hour working in the peach groves that were abundant in the eastern Valley in the early part of this century. When he was 16, Avila said, he helped build the McKinley Home for Boys in North Hollywood. Later, he worked on the construction of the Lakeside Golf Course in Toluca Lake, earning 50 cents an hour.

He said he was told by a friend that the Lankershims needed a caretaker and went to apply for the job.

Asked 4 Questions

“I guess Jack Lankershim thought I was somebody dependable,” Avila said. “He asked me only four questions: my age, where I lived, where I came from and where I had worked before. Then, he hired me.”

He said he went to work for the Lankershims on June 19, 1929. The pay was 50 cents an hour for nine hours of work, six days a week. Avila said he received his check every Monday in the mail.

When the Avilas married in November, 1929, Avila said, Jack Lankershim asked the newlyweds to move to the ranch. His salary was raised from 50 cents an hour to $125 a month, Avila said, and he was put in charge of running the estate.

“I was given a free hand,” Avila said. “The only thing Jack told me when I bought anything for the ranch was to make sure it was made in California. They had respect for working people. They treated us well. They were very, very nice people.”

When he left the Lankershims’ employ after more than 20 years, Avila said, he received a $1,500 “separation allowance” and some furnishings from the estate. He worked for General Motors until his retirement 12 years ago.

The Avilas bought the half-acre on which their present house stands for $4,500 in the early 1950s.

Other Volunteer Work

Before they built their ranch-style home on the site, Maria Avila said, they used to go there to pick oranges.

Besides preserving the Lankershim name and becoming involved in other historical causes, the Avilas volunteer two days a week at the Spastic Children’s Foundation in Canoga Park. The foundation has been the home of their only child, a daughter, Esther, now 48, for the last three years.

“She stayed at home with us until then,” Maria Avila said.

Francisco Avila said he had several opportunities to buy parcels of the Lankershim estate as it was being sold bit by bit over the years. He said he bought a house and some land in North Hollywood in 1935 for $800. He put $200 down on the property and made $25-a-month payments on it.

The couple never lived in the house but rented it until it was sold for $15,000 in 1946.

“I passed up a chance to buy 20 acres at Lankershim and Sherman Way for $500 an acre in 1938,” Avila said. “I’ve been kicking myself ever since.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.