‘Galapagos’: Vonnegut Explores Big-Brain Theory

- Share via

NEW YORK — The big trouble, in Kurt Vonnegut’s view, is our big brains.

“Our brains are much too large,” Vonnegut said. “We are much too busy. Our brains have proved to be terribly destructive.”

Big brains, Vonnegut said, invent nuclear weapons. Big brains terrify the planet into worrying about when those weapons will be used. Big brains are restless. Big brains demand constant amusement.

“Our brains are so terrifically oversized, we have to keep inventing things to want, to buy,” Vonnegut said with a shudder. “If you think of the 8 million people of greater New York charging out of their houses every day in order to monitor the planet, it is a terrifyingly destructive force.

‘Stupidity May Save Us’

“Among other things,” he said of this giant computer lodged between humanity’s collective ears, “it is capable of creating the Third Reich of Germany, which in fact so demoralized the world that I don’t think we’ll ever recover.”

The brain: “I think stupidity may save us,” Vonnegut said. “I think we are too damned smart.”

His big-brain theory is at the heart of “Galapagos” (Delacorte Press), his 11th novel: Big brains have gotten civilization in so much trouble that its remnants have ended up on one of the barren islands off Ecuador where Darwin concocted his theories of evolution. Of course by this time, a million years in the future, mankind’s descendants not only have vastly smaller brains, but also flippers, beaks and, in some cases, soft, seal-like fur.

An Alarming Idea

The idea was so alarming in certain quarters that when an excerpt of “Galapagos” was to appear in Esquire a few months ago, an agitated young fact checker called Vonnegut at home, insisting that there were no records of de-evolution.

“Sure there are,” Vonnegut said. “For one thing, the penguins presumably gave up on flying at some point or another.”

Inverse evolution was, after all, an idea that popped into Vonnegut’s own brain four years ago after a cruise he took to the Galapagos with his wife, photographer-author Jill Krementz.

“Absolutely nothing happened on that cruise,” Vonnegut remembered. “Nobody fell in love. Nobody got drunk. Nobody fell overboard. No shipboard intrigue. Nothing.”

But after he got home, back to his big, airy town house in the Manhattan literary enclave known as Turtle Bay, Vonnegut got to thinking: “Suppose human beings were shipwrecked on those islands? What would happen? Because all those animals out there have no business being there, you know. So I was thinking, how would human beings adapt?

“Of course there were no things to make tools out of out there. Just twigs, maybe some lava for hand axes. We would have to become very different sorts of animals.”

Now many scientists might view Vonnegut’s thinking as unconventional. Even Kurt Vonnegut would readily concede his logic sometimes transcends the ordinary.

Said Vonnegut: “My brother is in the same business. He’s nine years older than I am. He’s a research scientist. We look at things in an unusual way.”

A physicist, Vonnegut’s brother “has had a great deal of success in turning things upside down and looking at them in unusual ways.” For example, while so many of his physicist colleagues were busy smashing atoms and such, “my brother got very, very interested in weather. He did some research and he realized nobody knew much about it.”

Specialize in Science

At Cornell University, Kurt Vonnegut had started out intending to specialize in natural sciences. But soon after signing on as a biochemistry major, he realized he had “no gift for it whatsoever.”

Still, the scientist’s curiosity persisted. As Vonnegut became more focused on the chemistry of the cranium, “Everybody else was hoping we would develop an extra lobe on the brain so we would get smarter and cure cancers and end wars and all. But I was willing to entertain the notion that maybe that wasn’t the way it worked, that the bigger our brains get, the more catastrophic it becomes.”

Talking about the vast computer, the great big mass of neurons humans carry atop their shoulders, Vonnegut is struck by a further irony. “We are extravagantly alert,” he observed, “and frequently wind up in hospitals because our computers are so overheated.” But in fact, “what we want to do, so many of us, is go lie on a beach. That is what people want to do, to swim in a blue lagoon.”

And so, to Vonnegut, a future, a million years from now, of a de-evolutionized society on a tiny Pacific island didn’t sound so bad at all.

“Because look at what the future actually is, now. It’s old people’s homes. It’s bag ladies. Wouldn’t it be nicer if everybody, absolutely everybody, could look forward to lying on a beach?

“Our cousins, the seals and sea lions are so happy. They are so content.”

Luckily for mega-brained mankind, Vonnegut said, “It is a very forgiving planet. Grotesque mistakes of evolution are forgiven.”

For instance, “I mean, what is so great about a giraffe? Or the elephant? It’s much too big.”

On the other hand, there is the rhinoceros. Lauded Vonnegut: “Well done, Mother Nature.”

Even among the surviving species, “There are all these ludicrous mistakes. And we have plenty of fossils that show us these hilarious variations throughout history.” Said Vonnegut: “I think we are one.”

Upstairs, napping at that very moment, was Vonnegut’s soon-to-be-3-year-old daughter, Lily. “One day,” her father said, “she is going to learn about World War I, World War II, what we did to the Indians and all. And she is going to conclude, as she is bound to, that we are terrible animals.” This is difficult stuff. More than outrageous, it sounds bitter, borderline angry, certainly pessimistic. So how come Vonnegut’s books are so funny? Why do people laugh out loud at the antics of Kilgore Trout, or now, in “Galapagos,” of Trout’s descendant?

Well, Vonnegut said, it’s not really that he thinks mankind stinks. It’s not that simple. It’s not that seamy. “I say what Anne Frank said. That people’s hearts are good.” But he tacks on an addendum: “It’s their brains that get them in trouble.”

As he points out, “I have met utterly vicious and destructive people who are good at heart. But their brains, there is their seat of evil.”

When he is not writing, pounding away on his typewriter or playing chess on his Apple computer, Vonnegut leads “a didactic life,” delivering lectures and speeches “where I say flat out what I think.”

Lecture Topic

So if The Big Brain were a lecture topic, “I might leave the question hanging: Do I really believe we should become more stupid?”

But in fact, “actually,” Vonnegut said, “all I am pleading for is high intelligence put at the service of humanity.”

For, he said, “the most upsetting thing about being alive today is that our problems are soluble. And there seems to be very little interest in solving them.”

One big problem, a growing one in America, is illiteracy. As such, he suggests, “the book is a practical joke--and a good one, I hope.”

It is a fable, “a seduction.” He laughed. “You have to bribe the reader to read. Books require active participation on the part of the reader. There is no other art form that does.”

That is one obstacle faced by the author, or the characters of a book. Another is that “it is so hard to learn to read that most people never learn to do it. Charlemagne tried and tried to learn to read, but he never could get it right.”

Vonnegut’s book, his latest one, “is the length of ‘The Bobbsey Twins,’ and it took me three years to get it right.”

There was one big technical problem: “I didn’t dare say who was telling this story until the reader had a deep commitment to the book.”

The writer who wanted to could become quite despondent about all these roadblocks that his craft encounters.

Vonnegut shrugs. “Oh, I don’t know.” For in the end, Vonnegut said, “Look, people ought to be content with nice days. They ought to be able to really treasure it when they say ‘that was a nice day.’ ”

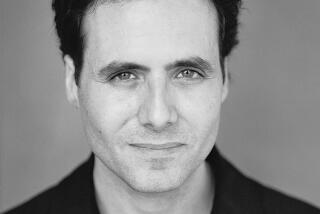

Kurt Vonnegut is 63. He is 6 foot 3, craggy and seemingly forever wrinkled. His hair is a mop of curls, equal parts gray and brown, and each lock seems determined to carve a route of its own. Vonnegut smokes ceaselessly, and once defined a writer as someone “who makes his living with a mental disease.” As for his own apparently chronic bout with that condition, his contract with Delacorte calls for one more volume in a five-book contract.

Sitting in his dining room, Vonnegut laughed, heartily and abruptly. The sun was stretching through the clouds outside. It was time to take Lily for an afternoon outing to her favorite cafe.

“There is too much thinking about the future,” he said. “Really, the culmination of all the hopes of mankind is a very pleasant day.”