Day With Mays Helped O.J. Escape the Ghetto

- Share via

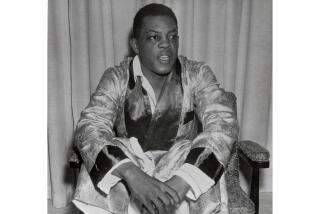

O.J. Simpson and his teen-aged friends thought they belonged to “social clubs.” Others around San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood had a more suitable description for such groups: “Gangs.”

Semantics aside, it’s safe to say that Simpson, Heisman Trophy Award-winning tailback at USC and 11-year NFL veteran, was a problem child.

According to one biographer, Simpson “led an aimless, street-corner existence, running with a gang and coming close to serious trouble with the law on several occasions before his energies found a positive outlet in athletics.”

A bit dramatic, but accurate. Simpson was in a gang and he was in trouble with the law. But his energies didn’t suddenly “find” a positive outlet in athletics. He had a little help.

Before he could excel in two sports--track and football--at USC, before he could become one of the greatest running backs in National Football League history, he needed some encouragement, someone to show him there was a way out of the ghetto.

That inspiration came in the form of a visit from Simpson’s hero, Willie Mays.

The year was 1962 and Simpson was a 15-year-old sophomore at Galileo High School. Simpson, reared by his mother, Eunice, had been arrested for involvement in a gang fight. He had just spent a weekend in a correctional center.

He came home that Monday afternoon and fell asleep in his room, but he was awakened by voices downstairs. Simpson went into the living room and there stood Mays, star outfielder for the San Francisco Giants.

“He was my absolute hero,” Simpson said.

Mays’ visit had been arranged by Lefty Gordon, who ran the Booker T. Washington Community Center, the local club where Simpson played several sports. Gordon thought that, pushed in the right direction, Simpson might have the potential to become an outstanding athlete.

There were no speeches. Mays didn’t give Simpson the obligatory “stay in school and stay away from alcohol and drugs” line. Rather, he just let the youngster spend the rest of the afternoon and part of the evening with him.

Mays took Simpson to the cleaners to pick up some clothes and then brought him to his home in St. Francis Hills, a far cry from the government housing projects where Simpson lived.

Simpson then sat in on a meeting between Mays and representatives of a local charity. Mays then brought him home.

That was it. No advice or words of wisdom. Just a day to hang around with The Say Hey Kid.

For Mays, it was probably nothing more than the average day with a troubled youngster. He did it often and considered it part of his job.

But for Simpson, the day with Mays had long-lasting affects.

“Here was Willie Mays, who I had always envisioned as my hero, taking time to spend with me,” said Simpson, 38, who today is a commentator on ABC’s Monday Night Football. “We all have our heroes, and we tend to view them as larger than life. But to have that hero pay attention to me, it made me feel that I must be special, too.”

Simpson realized that day that Willie Mays was an ordinary person.

“After spending time with him, my dreams became realistic goals, because I was able to touch the man,” Simpson said. “He became a guy like me, with problems--his clothes weren’t ready at the cleaners.

“He made me realize that we all have it in ourselves to be heroes. The feeling was, he’s done it, so can I. I can have people who want to watch me perform. He showed me that I could succeed and I was a lot more determined to succeed after that experience.”

Simpson went on to become a star at City College of San Francisco and later at USC, where he led the Trojans to a Rose Bowl championship and the national title in 1967.

He was the first player selected in the 1969 draft and spent nine seasons with the Buffalo Bills and two with the San Francisco 49ers. Simpson rushed for 2,003 yards in 1973 and was an All-Pro selection five times.

Throughout his illustrious career, Simpson, like Mays, has spent many days with problem youths, in hopes that he might have the same effect on them that Mays had on him.

That day spent with Willie Mays may not have been the biggest factor in Simpson’s success, but it certainly provided the incentive for Simpson to strive toward his goals.

“He (Mays) probably had no idea what would become of me (at the time),” Simpson said. “He may have forgotten the whole incident.”

Simpson never will.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.