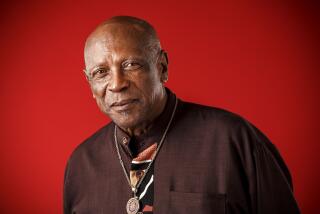

Stepin Fetchit, Noted Black Movie Comic of ‘30s, Dies

- Share via

Stepin Fetchit, the black comedian who became a Hollywood star in the 1930s by playing lazy, slow-moving, easily frightened characters, died Tuesday of heart failure and pneumonia at the Motion Picture & Television Hospital in Woodland Hills. He was 93.

Fetchit, born Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry, came to Hollywood in the late 1920s and made a small fortune portraying shuffling, idle men who rolled their eyes in fright and ignorance at the complexities of the world.

The unsophisticated, subservient portrayals were later viewed by many as an insult to American blacks, but Fetchit never saw much harm in the stereotype.

“Just because Charlie Chaplin played a tramp doesn’t make tramps out of all Englishmen, and because Dean Martin drinks, that doesn’t make drunks out of all Italians,” he said in a 1968 interview with The Times. “I was only playing a character, and that character did a lot of good.”

Film historians said Fetchit was the first black actor to receive feature billing in American movies not aimed specifically at black audiences, and Fetchit argued that he opened doors for other blacks in the film business.

“I defied the law of white supremacy,” he said. “I had to defy a law that said Negroes were supposed to be inferior. . . . I became the first Negro entertainer to become a millionaire. All the things that (Bill) Cosby and (Sidney) Poitier have done wouldn’t be possible if I hadn’t broken that law. I set up the thrones for them to come and sit on.”

He sued Cosby and CBS over the use of some of his film clips in a 1968 television retrospective of black history, claiming that he had been portrayed as “the symbol of the white man’s Negro, the traditional lazy, stupid, crapshooting, chicken-stealing idiot.”

A federal court judge dismissed the suit on the grounds that Fetchit was a public figure.

Born May 30, 1892, in Key West, Fla., to parents with a fondness for presidents and statesmen (hence his names), young Lincoln Perry was raised in Montgomery, Ala.

He ran away from home at the age of 14 and wandered about the South with several plantation shows--black shows for farm workers that played weekend nights.

Perry advanced to minstrel groups, carnival companies and medicine shows.

He was broke at one point in Oklahoma, when a horse named Stepin Fetchit won him $30. Perry wrote and sang a tune about the horse, and a Muskogee, Okla., theater manager liked the tune and stuck Perry with the name.

Fetchit came to Hollywood, making $300 a week in vaudeville and broke into film with “In Old Kentucky” in the late 1920s.

“I was a gentle character,” he recalled in an interview four decades later. “I played the harmonica and just didn’t care about working . . . . I stole the picture.”

Fetchit was placed under contract. He worked in dozens of films through the 1930s, earned a couple of million dollars and lived well--big houses with Chinese servants and cashmere suits, parties and expensive cars, including one flashy model with “Stepin Fetchit” emblazoned in neon along both sides.

He made “Stand Up and Cheer,” “Miracle in Harlem,” “The Country Gentleman,” “David Harum,” “Steamboat ‘Round the Bend” and a dozen other films with such stars as Shirley Temple, Will Rogers and Janet Gaynor.

But the money was spent as quickly as Fetchit earned it. His movie appeal went sour, and a production company he formed to film the lives of such black athletes as Jack Johnson and Satchel Paige went nowhere. In 1947 he declared bankruptcy and hit the road again, singing and telling jokes.

Little was heard of Fetchit until he resurfaced in Chicago in the mid-1960s: The once high-living star was a charity patient, hospitalized for a prostate operation.

Life became even harder a few years later when Fetchit, working a Louisville, Ky., club date, learned that his 31-year-old son had murdered three people, including the son’s wife, before turning the gun on himself in a shooting spree along the Pennsylvania Turnpike. A total of 17 other men, women and children were wounded or injured in the bizarre highway incident in 1969.

Fetchit, who had last seen his son two years before while playing a Chicago date, said at the time of the murders: “I can’t understand it; he was such a cool, calm and intelligent boy.”

A few days later, the young man’s uncle, a New York City sociologist and official of an anti-poverty program there, blamed the young man’s “paranoid” sense of frustration about racial relations.

Fetchit, a Catholic who had recently converted to the Muslim faith, took the incident hard. He settled in Chicago, hoping for the best, hoping for more work.

“There’s a great lot of movies that could use me,” he said in 1969, discussing the possibility that Hollywood might find work for him again. “They’ve said I’m such a dumbbell. They don’t know how wise I could be in place of all those that they got.” One minor movie role in “Amazing Grace” came along in 1974.

He entered the Motion Picture Country House in 1977, a year after suffering a stroke, and spent the final years of his life there fighting a series of illnesses.

Funeral arrangements are pending.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.