MOVIE REVIEWS : MAKING MOST OF INFLUENCE : ‘Down and Out in Beverly Hills’ Is Up and at ‘Em With On-Target Satire

“Down and Out in Beverly Hills” (selected theaters) is depth-charge comedy; the final kick comes in the car on the way home. Paul Mazursky has pinned his butterflies deftly: the Whitemans, a self-absorbed, preposterously rich family in Beverly Hills, hard at work on the meaning of life after taxes. He observes their gilt-edged, guilt-ridden foibles with a keen eye but mostly with affection, as behooves a man virtually making home movies on his own block.

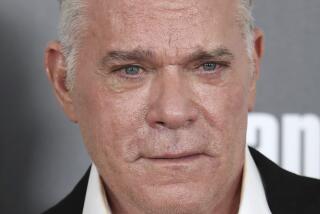

As always, Mazursky’s casting is immaculate. The film is anchored by two perfect performances: Nick Nolte’s and Richard Dreyfuss’. Nolte is Jerry, a shrewd, shambling piece of flotsam from the tide of the late ‘60s, who in trying to end it all in the Whitemans’ swimming pool becomes a catalyst in all their lives. Dreyfuss is Dave Whiteman, his benefactor, becalmed in the horse latitudes of marriage with a wife who is prey to every passing guru. In touching a funny bone, both men touch a nerve as well.

Sly and perceptive, Bette Midler is Barbara Whiteman, the Beverly Hills matron supreme, bustling on her backless pumps through her peach-on-apricot living room as though she were perpetually drying her nails. Unfortunately, there’s less to her role than to those of the men around her.

But for all its genuinely funny moments and its mix of outrageousness and insights, “Down and Out” remains curiously unsatisfying in the way it resolves the Nolte character.

Even more than in the Jean Renoir classic, “Boudu Saved From Drowning,” on which Mazursky and his co-writer Leon Capetanos based their screenplay, the determinedly free-spirited Jerry (the Boudu of the original) changes the lives of everyone he meets. He’s one of those ‘60s Renaissance men, who can dispense orgasms or revolution with equal aplomb. His talent now is to challenge and to change people around him, while cannily evading change himself. One of the genuine joys of the movie is Nolte’s equilibrium in the role. Clean up his scuzzy surface and he doesn’t turn into an upright, foursquare tidied-up leading man--the lurch is there in Jerry’s soul.

Although Jerry may be an opportunist, we shouldn’t believe that he’s a charlatan. Mazursky first goes to great pains to hint that Jerry’s talents are real: He plays Debussy feelingly; his massage (plus) would do credit to an ashram master, and, as he tosses off Hamlet’s “What a piece of work is man . . . “ quietly for Dreyfuss, you believe that he might certainly have been an actor. He just doesn’t want much truck with responsibility.

However, in the film’s enigmatic and unsatisfying final sequence, Mazursky undercuts everything we’ve come to believe about the man; we’re left feeling cheated, as though Jerry had been neutered into a family pet.

Although this ending works against the film as a whole, “Down and Out” still has nice individual moments: the spellbinding fury of the Whitemans’ next-door neighbor Orvis Goodnight (Little Richard), livid at the speed at which armed patrol guards and a helicopter arrive at his neighbor’s house--but not at his. Or the updating of the Andy Hardy/Judge Hardy chats: Today’s Beverly Hills 15-year-old leaves his pop a homemade videotape of his state of mind, a miasma of sexual confusion enough to have Dad mainlining Maalox for a month.

Good, too, is the witty selection of songs used to connect the sequences; instead of the usual flaccid attempt at a pop hit, the film makers use the Talking Heads’ “Once in a Lifetime” and Randy Newman’s “I Love L.A.”--cutting edge enough for any film. Details of the Whitemans’ house have the same nice edge; this may kill any inclination you had to provide faux marbre for every little nook and cranny, Metropolitan Home notwithstanding.

But at bottom, it’s not “Down and Out’s” genial satire or its frenzy that stays with you longest, nor even its dubious achievement as the first R-rated film from Disney, accomplished by the gratuitous insertion of one word which never would be missed.

No, it’s the depth and profound (newfound?) humanity to Dreyfuss’ husband and father, a men s ch withal, and Nolte’s gloriously iconoclastic vagabond, a man who, given the choice between a dog and his fellow humans, might just settle for the dog. The midnight rambling of these two--bound together in a reverie of Snyder, Campanella and Drysdale--captures what is sweet and best about the film.

‘DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS’ A Touchstone Films presentation in association with Silver Screen Partners II of a Paul Mazursky film. Producer/director Mazursky. Screenplay Mazursky, Leon Capetanos based upon the play “Boudu Sauve Des Eaux” by Rene Fauchois. Co-producer Pato Guzman. Camera Donald McAlpine. Production design Guzman. Editor Richard Halsey. Costumes Albert Wolsky. Music Andy Summers. Art director Todd Hallowell; set decorator Jane Bogart. Production sound Jim Webb, Crew Chamberlain. With Nick Nolte, Richard Dreyfuss, Bette Midler, Little Richard, Tracy Nelson, Elizabeth Pena, Evan Richards.

Running time: 1 hour, 43 minutes.

MPAA-rated: R (persons under 17 must be accompanied by parent or adult guardian).

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.