Writer Knows His Place--at the Typewriter

For someone who has had 49 novels published in 19 years--books that together have sold upward of 37 million copies worldwide--he remains possibly the least-known best-selling author in America.

But that hasn’t bothered Dean R. Koontz of Orange, whose latest novel, a suspense thriller called “Strangers” (G. P. Putnam’s Sons: $17.95), will reach bookstores in late March.

According to the normally publicity-shy Koontz, who received a $275,000 advance for “Strangers,” there are two basic types of literary careers.

“There’s a big flashy career where somebody comes in like Peter Benchley with ‘Jaws’ and-- boom --it’s a household name,” Koontz said. “Then there’s the other type of career that starts slow, and the writer tries to do better work each time and struggles with it and gradually builds up a large body of work and more readers. And usually it’s the kind of writer who gets reviewed--and I’ve been well reviewed--but doesn’t get off-the-book-page coverage, or doesn’t get book-page interviews or that sort of thing. Just a nice review and that’s it, and nobody pays a lot of attention. But then it builds.”

Koontz, who has had nine of his suspense-thriller novels--including “Whispers,” “Phantoms” and “Darkfall”--reach the best-seller lists, says he hopes he falls into the latter category.

And “Strangers,” which Putnam’s is backing with a 75,000-copy first printing and a $75,000 advertising campaign, just may be the breakthrough novel that will give Koontz recognition beyond his loyal core of readers and book reviewers. (His previous work has been praised by the London Times as “emotionally and intellectually stimulating” and by the New York Times as “real suspense . . . tension upon tension.”)

Terrorized by Fear

“Strangers,” which will be a main selection of the Literary Guild in April, is a suspenseful, psychological horror story about six people--all strangers to one another--whose lives are being terrorized by a mysterious fear that is, as the book jacket teases, “only a mask for a deadly secret--a secret they cannot fathom.”

In light of his publisher’s enthusiasm for “Strangers,” Koontz plans to raise his normally low profile--at least to a degree.

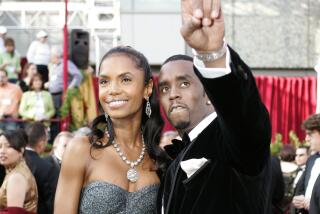

“I’m trying to strike a balance,” said Koontz, who at 40 is an articulate, mild-mannered man, trim and neat down to his carefully pressed designer blue jeans.

With a grin, he added, “I always like to point out to my publishers that Mario Puzo refused to do anything for ‘The Godfather,’ and it didn’t hurt the book. On the other hand, I can see their point of view. You at least want to do a little. But I’ve never really done it. I felt my place was at the typewriter.”

Indeed, for Koontz that means working at least 10 hours a day--no less than six, and often seven, days a week.

“There’s something about plunging into a book and becoming totally immersed in it so that it becomes your entire world,” Koontz said. “That brings me deeper into the story and, I think, works better for me. I get more empathetic with the characters, and they seem more like real people to me. And when something is going real good, I’m just loathe to get up from this thing.”

The slightly built author, with dark, thinning hair and a drooping mustache, was seated in a padded leather desk chair next to the word processor in his office--a stylishly appointed spare bedroom in the large, two-story house he shares with his wife, Gerda, in a “private equestrian community” in the hills east of Orange.

Koontz, however, does not belong to the horsy set. “The idea of a horse,” he said, “is almost as horrifying as some of the things I write about.” Koontz is more the indoorsman type, with a penchant for collecting art glass, paintings--and books. About 25,000 volumes are encased throughout the house--in every room, Koontz joked, but the kitchen and bathroom.

“Books are more or less the center of my life,” he said.

It’s been that way since he was a boy growing up during the ‘50s in Bedford, a tiny town in rural Pennsylvania.

It was, he said, “an exceedingly unpleasant childhood, and I escaped into reading. And I was always reprimanded for that. I was told by my parents that books are a waste of time. It’s almost a cliche, but it’s true: I used to read in bed with a flashlight under the covers after I was supposed to be asleep.

“Anyway, I fell into a love of books, and what I wanted to do more than anything else was to create books that would give other people the kind of experiences I had with books.”

Koontz started writing science-fiction stories in his early teens because, he said, “that’s what I read.” While he was majoring in English in college and “struggling along on not very much money,” a professor entered one of his short stories in Atlantic Monthly’s yearly college writing competition. The story won a prize for fiction.

“Everybody was so impressed with that. But I turned around and sold the story to a magazine for $50, and I was much more impressed with that because that $50 did a lot for me,” he said. “I came from a very poor background, and it’s always in the back of my mind. In addition to loving what I’m doing, partly what drives me is the fear of ever going back to being poor again.”

After college, Koontz spent a largely unpleasant year working in a federal poverty program in a small Pennsylvania coal-mining town, teaching and counseling kids who were supposed to have “tremendous potential” but who actually were “real trouble-makers.” Koontz knew he was in for a rough time, he said, when he discovered that the man he replaced had been run off a road and beaten up by the youngsters he was supposed to be helping.

Koontz stayed with the program a year, then taught English in a regular school district for a year.

“I liked the kids, but I didn’t like dealing with the administration and the bureaucracy of education,” he said. “By that time I had sold three paperbacks and a score of short stories, and my wife said, ‘Listen, I’ll support you for five years. If you can’t make it (as a writer) in five years you’re never going to make it.”

‘Big Productive Years’

So in 1969, at age 24, he became a full-time writer. During the next few years, he wrote nearly 20 science-fiction paperback originals and several short-story collections.

“Those,” he said, “were my big productive years. I was real young, and you couldn’t make very much per book, so you either were doing it out of love and starving to death or doing two or three or four books quickly in order to have time to do one properly, which is the thing I hated about it: You didn’t have time to do it properly.”

Koontz’s last science-fiction novel was “Demon Seed,” which was published in 1972 and later made into a movie starring Julie Christie.

Before moving into what he calls “mainstream thrillers,” however, Koontz wrote a comic novel called “Hanging On.” “It was very well reviewed, but I learned a terrible lesson: that comic fiction generally does not sell very well. Very few people have ever managed to make much of a career of it.”

Part of the reason Koontz is not better known among the general public is because 19 of his novels were written under five different pen names: Brian Coffey (“The Face of Fear”), Owen West (“The Fun House”), K. R. Dwyer (“Shattered”), Aaron Wolfe (“Invasion”) and Leigh Nichols (“The Key to Midnight”).

He started using pen names early in his career, he said, because he was writing in radically different styles and was advised by his agents to release some of his books under pen names so he wouldn’t confuse readers.

Ideas Come Easily

Koontz has since stopped using pen names, with the exception of one: Leigh Nichols, under which he has had four paperback best-sellers. He recently sold his fifth Leigh Nichols thriller to Avon.

Ideas for novels come easily to Koontz, who has been praised by critics as a gifted storyteller with a riveting narrative drive. After a day or two of thinking, Koontz said, he usually comes up with 10 different book ideas. “And they’ll all be very strange ideas,” he said with a grin. “People like my books because they have really unusual premises.”

Koontz’s stories typically revolve around what appears to be an impossibility. His best seller, “Whispers,” for example, is about a woman who is attacked by a would-be rapist. She kills her attacker, and the reader is taken through the process of the body going to the morgue and being buried. A few days later, the woman is attacked by the same man she presumably killed. It is not, however, a supernatural story. As with his other suspense novels, Koontz said, “There turns out to be a logical explanation that keeps the reader guessing until the very end.”

For the past decade, Koontz has earned an increasingly handsome living from writing. His wife, Gerda, quit her job as a receptionist in 1975 to work for him full time, helping with research, bookkeeping, correspondence and proofreading--all of which, Koontz says, “frees me up considerably.”

But Koontz, who has earned about $300,000 from “Whispers” in addition to another $250,000 from film options on the novel, said he is at the point in his career where money, once “a desperate consideration,” has become “sort of secondary.”

As a writer, he said, “you’re in it to communicate, you’re in it to captivate people, not solely for the money. And there comes a point where I wouldn’t be working 80 hours a week if it was for money alone. I’d be taking time off to enjoy it.”

A Good Cry Over Dickens

What drives him to keep working harder and harder, he said, “is when I read a good book.” A few months ago, he said, he reread Charles Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities,” staying up in bed late into the night to finish the book.

Recalled Koontz: “I just broke down and cried. I sat in bed weeping and Gerda woke up and said, ‘What’s wrong?’ And I said, ‘This beautiful book.’

“And that, in a sense, is what keeps you going--the hope that sometime you might write some glorious kind of prose, something that will touch people’s emotions that deeply,” he said. “And that, for me, is what it’s all about.

“I’m known for writing page-turners, thrillers and things like that, and a lot of writers who are young will come to me or send me their manuscripts and ask me essentially, ‘What’s your major piece of advice?’

“And I always come back to: Don’t just try to scare people, and don’t just try to keep them in suspense. If you really care about writing, what you want to do is also make them laugh, make them cry, give them a sense of melancholy--just wrench every human emotion out of them you can. And if you can do that, then you’re doing something worthwhile, and that’s really the goal to shoot for.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.