ART--OF, BY AND FOR ALL AMERICANS

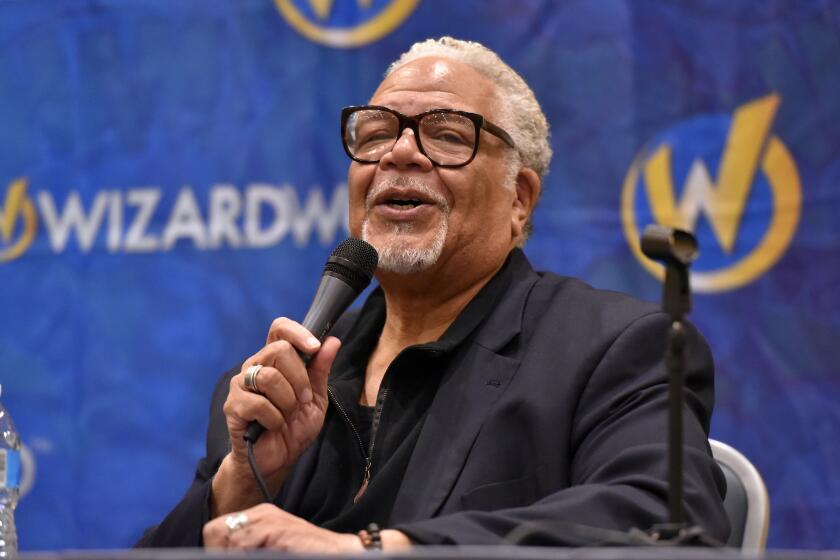

David C. Driskell believes that the contribution of black American artists to the historical development of art in this country is “no different” from that of their Caucasian counterparts, and that its impact should never have been excluded from a comprehensive history of American art.

“You had a group of people who were able to leave a legacy in the arts in many ways equal to what was done by white American artists--without (cultural) institutional support,” the art historian argues.

In his most recent public effort at enlightenment, Driskell has curated “Hidden Heritage, Afro-American Art, 1800-1950,” on view through June 2 at the California Afro-American Museum of Art.

Washington’s Bellevue Art Museum and the Art Museum Assn. of America organized the 84-piece survey of paintings, drawings and sculpture by 42 artists. Though the works’ creators may be little known, their various styles, from a calm, Inness-like scenario by Edward Bannister to an angular, Cubist painting by Hale Woodruff, are easily pegged to their respective schools or movements.

“Black Americans contributed to numerous periods in art history,” explains Driskell, 55, here on a short hiatus from his job as professor of art history and studio art at the University of Maryland. Artists such as the early 19th-Century landscape painters Bannister and Robert Duncanson participated in the Hudson River and the Barbizon schools respectively, he said.

“Mary Edmonia Lewis contributed to Neo-Classicism, and at the turn of the century, Henry O. Tanner was very much aware of European Impressionism and equally caught up with the Expressionists.

“Then when we come to the 20th Century proper,” Driskell continues, “for the first time black artists looked back to their African ancestry (particularly during the ‘20s Harlem Renaissance) and found they had an important heritage that had not been exploited. They glorified their ancestral past and created their own black images; they reflected their own life styles, devoid of stereotypes, and found an identity within American culture and society.

“This paved the way for the cultural revolution among black artists of the ‘60s, who glorified their own images with ‘black is beautiful.’ ”

“Hidden Heritage,” which opened in Washington late last year, will travel to 10 museums on a two-year national tour. Post-World War II works, such as paintings by Horace Pippin, Archibald Motley Jr., Romare Bearden and Joshua Johnston, sculpture by Elizabeth Catlett and graphics by Charles White, are also included in the exhibit, which serves as an adjunct to Driskell’s earlier curatorial effort, “Two Centuries of Black American Art, 1750-1950,” shown at the County Museum of Art in 1976.

Driskell, who “somewhat sacrificed” his own career as a painter to devote himself to teaching a colorblind, non-sexist history of art, would like to curate a show of black American art from 1950 onward. Though the Georgia-born scholar listed several changes in contemporary artists’ styles, he says he sees both aesthetic and social influences of the “Hidden Heritage” artists on the current creative scene.

“The contemporary artists I’ve interviewed, like (New Yorkers) William T. Williams and Jack Whitten, talk about the impact people like Tanner have had on their art, down to the plasticity of his technique. And they talk about the spirituality of form created prior--the fact that the artists of the ‘20s acknowledged the importance of their African heritage and worked to imbue their art with the same power and vital force” as their ancestors.

Also, some of the artists in “Hidden Heritage” have had a hand in the development of a growing support system for black American artists within the black community, Driskell notes, as evidenced by about 100 facilities across the nation for the exhibition of black American art.

“The ‘Hidden Heritage’ artists have helped that cause historically, and those still alive have helped boost the organization of these cultural institutions,” he says, then quickly adds, “I’ve always felt that the answer to the survival of black art was to generate support and patronage in the black community. The home base ought to be ‘I recognize my own worth here. I’m willing to buy (black American art), to support it and to preserve it, because it’s a vital part of my culture.’ That should be the ultimate goal that is sought.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.