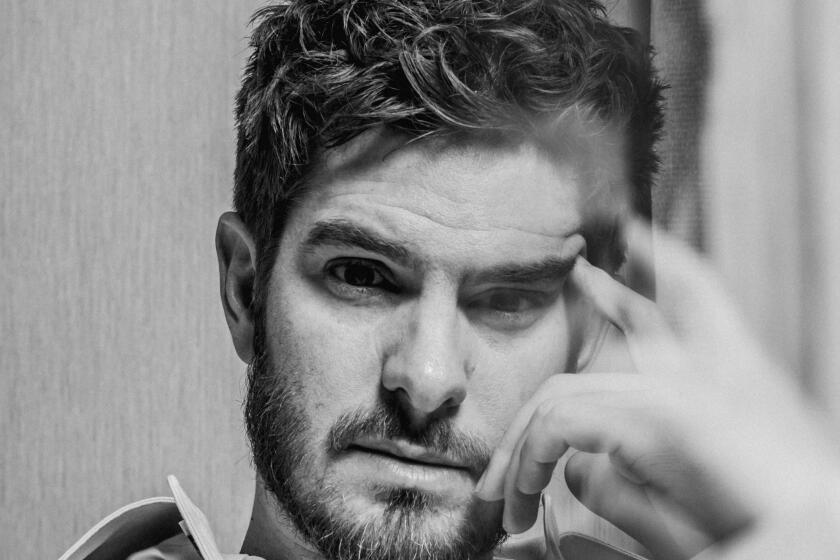

USX Faces Tenacious Suitor in Australian Holmes a Court

In April, 1985, lawyers for Asarco, a New Jersey-based mining and minerals company, confronted Australian financier Robert Holmes a Court--then mounting a takeover run at the company--with the scenarios of nine takeover attempts that he had made in the previous seven years.

“Your job is a buyer and seller of companies, is that a fair statement?” one lawyer asked.

“You would be very wrong on that,” Holmes a Court politely corrected the attorney. “Ninety percent of my hours and time and thought are in the administration of (my) company.” In any event, he added, the correct figure was 25 or 30 takeover attempts.

What appears to be his latest foray was disclosed this week when USX Corp., formerly known as U.S. Steel Corp., said Holmes a Court had announced his intention to acquire up to 15% of its stock. Although not his first transaction in the United States, the move focuses American attention on a man known to many executives in Australia and Britain as far more than the administrator of Perth-based Bell Group Ltd., an Australian industrial concern with more than $3 billion in assets.

The soft-spoken Australian, born in South Africa 49 years ago to a family whose name echoes with its Norman roots, has become among the British Commonwealth’s best-known corporate acquirers. And the USX announcement makes Holmes a Court likely to become the best-known Australian in America since Rupert Murdoch bought the New York Post.

For three years he has waged a battle to take over Australia’s largest company, Broken Hill Proprietary Co., or BHP. In 1982 he took over Lord Lew Grade’s Associated Communications Corp., then the largest entertainment company outside of the United States and the producer of such films as “On Golden Pond.”

After discovering that the company was “within inches of going into receivership,” he presided over Grade’s ouster and restored the company’s health, partially through the $47-million sale of ACC’s Beatles song copyrights to rock star Michael Jackson.

Industry observers in the United States profess bewilderment over Holmes a Court’s goals in making a run at USX, whose stock has been sinking as its steel business languishes and the value of its oil and gas reserves falls. Some speculate that he is angling to provoke USX into selling him some of its petroleum holdings, others that he is hoping to frighten the company into repurchasing its stock from him.

Says Thomas P. V. Cameron, vice president of the New York arm of the Australian brokerage Ord Minett and an associate of Holmes a Court’s: “He thinks USX is a good buy. Everybody else is making up all the complications about it.”

Holmes a Court was a corporate lawyer in Perth in 1970 when he completed his first takeover--of a woolens manufacturer in the Australian Outback. As the cheapest company trading on the Perth Stock Exchange, it could be employed as a shell to incorporate mining claims.

Today, with a personal fortune estimated at more than $200 million, he is widely regarded as the richest man in Australia. His holdings include a television station and extensive oil and gas and mineral properties. He certainly boasts the possessions of an American-class mogul, including a string of thoroughbred racehorses (in 1984, one won the Melbourne Cup, Australia’s most important race) and a fleet of Rolls-Royce automobiles.

Cameron’s own description of Holmes a Court embraces the contradictions that many have found in the man’s personality:

“He’s very soft-spoken, very polite, a very winning sort of person. But he’s occasionally temperamental and even malicious; he doesn’t suffer fools gladly.”

As for his business scruples, he adds: “He’s always conducted himself with absolute propriety.”

Approached by Drexel

Holmes a Court insists that he conducts his business transactions with a scrupulous eye. When he makes a takeover bid, he said in his Asarco deposition, it is invariably genuine.

During the BHP fight in 1983 or 1984, he said, he was approached by Drexel Burnham Lambert, the aggressive American investment firm that has developed “junk bond” financing into a potent weapon for the U.S. corporate raiders. Drexel executives badgered him, he said, about providing their expertise, for a $15-million fee, at “seeking to acquire (a company) and pretending to acquire it and selling out at a profit--they said they liked that very much, too.”

Holmes a Court said he put off the Drexel bankers. “I told them I found it extremely uncomfortable and quite, quite contrary to the way I had ever acted in the past or wished to. I told them that if I ever did seek to acquire a company, that was my purpose; it was not to sell out at a profit, and I would feel extremely uncomfortable saying one thing and, in fact, doing another, and actually having a contract to give some people a share of the profit on a sellout.” He said he eventually stopped returning Drexel’s phone calls.

In the same testimony, Holmes a Court aimed harsh words at the American practice of “greenmail,” in which a speculator acquires a stake in a company and, after making suitably threatening noises, persuades its management to repurchase his shares at a profit. Securities analysts have jumped to the conclusion that greenmail is one of his possible goals in the USX purchase.

“As a transaction it offends me,” he said. “I would not seek to encourage such a transaction or be part of it.”

Yet Holmes a Court was making a careful distinction. Australian law forbids a company to purchase its own shares, a key element of greenmail. And Holmes a Court said he would not hesitate, on tiring of a takeover campaign, to sell his stake to another bidder, presumably at a higher price than he paid.

In fact, this maneuver has been characteristic of many of his takeover bids of the last six or seven years. In each case, he told the Asarco lawyers, he began with a legitimate acquisition attempt but found his target’s stock price rising beyond his ability to pay.

It is often charged that, by announcing his takeover intentions, Holmes a Court fuels this run-up himself in order to attract buyers for his own stake. In negotiating the sale of the Beatles song rights to Jackson, he similarly raised the specter of competing bids to move the sale along--exciting the market, as it were.

“Part of his game plan was to be a moving target--to create competition with several bidders,” recalls John Branca, the Los Angeles attorney who represented Jackson in the negotiations. Branca found Holmes a Court, with whom he dealt personally, to be cordial and personable, and added that “the key was not his skill so much at face-to-face negotiations but in his strategizing.”

Treated as Joke

Which is not to say that he shies away from confrontation. Holmes a Court stunned Australia’s business community with his bid for Broken Hill Proprietary, a steel, mining and petroleum company that is as staid an institution in Australia as Chase Manhattan Bank is in America. BHP executives at first treated the takeover campaign as a joke; the company’s chairman was quoted as comparing the attack to “a flea raping an elephant.”

Their smiles have since vanished, as Bell’s latest filings disclose that it has access to as much as $3 billion (Australian) in credit lines. Australian financial sources say that BHP quietly acknowledges now that Holmes a Court is a credible threat to win control of the vast company.

Meanwhile, many credit Holmes a Court’s bid with awakening the somnolent natural resources concern to the need for returning more of its profits to shareholders, in much the same way that T. Boone Pickens Jr.’s assault on several U.S. oil companies were simultaneously viewed with distaste at his manner and gratitude at upstreaming to shareholders the inherent values in the companies’ assets.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.