‘ARCHITECT’ OF AN ARTS CENTER

As credit is handed around these days for the Orange County Performing Arts Center, set to open with a lavish inaugural concert Sept. 29, there is little mention of Len Bedsow, a key figure in its development.

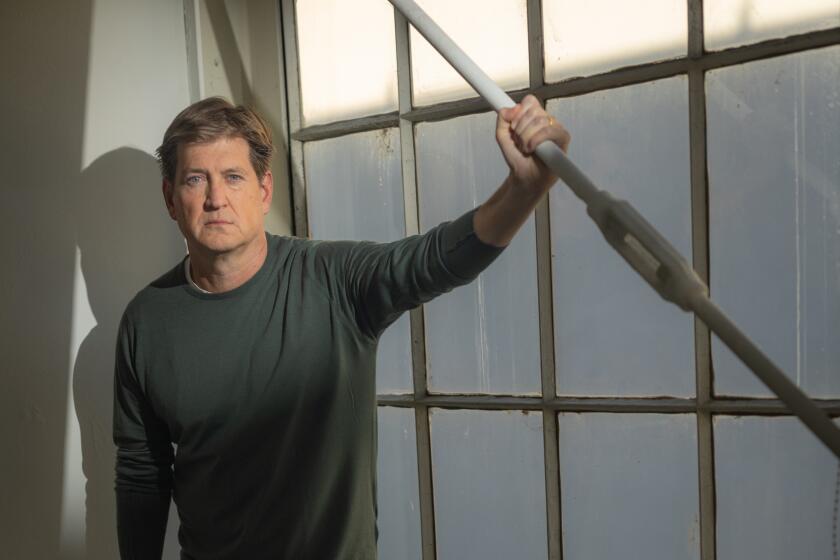

Yet it’s not hard to find people who say he deserves attention. Highly opinionated, sometimes overbearing, Bedsow was the Costa Mesa center’s first executive director during a crucial early phase, from 1981 to 1985. Many describe him as a stage-savvy executive with an evangelistic passion for the project. But he also made enemies and retired at 67 amid controversy.

He helped hire architects and acousticians, studied their plans and acted as their intermediary with his employer, the center’s board of directors. Fearing plush carpets would catch women’s high heels, he balked. Intrigued by the acousticians’ unusual concept, he gave encouragement. He bore down on Orange County donors for big money and went after New York agents for big artists.

His critics included local arts groups who said he ignored them and some board members who felt the same. There was also the center receptionist who named him and the center in a sexual harassment suit.

“There is no question that the physical building is because of Len,” said John Rau, former president of the center and the man who hired the burly Bedsow. “But he tried to do too much. He stepped on a lot of people’s toes.”

These days, Bedsow, 69, lives quietly with his wife in a small red-brick house in San Clemente. His beard is white. His love of conversation persists, as do traces of his Bronx accent.

Former general manager of the California Civic Light Opera Assn., well-known for its musicals and operettas, he can be jovial when recalling the pleasure of working on the center or turn as pedantic as if he were Henry Higgins and the center’s board were his Pygmalion.

“I had to make sure that they knew what the facts of life were,” Bedsow said. “And, you know, I found that I did not like the job. . . . You know how much it takes out of you when you’re dealing with amateurs! They didn’t know anything!

“Don’t get me wrong,” he added. “I don’t mean to speak ill of them. . . . . They were good people who wanted the best for their community.”

Reminders of the center appear everywhere in Bedsow’s home. Stickers showing the center’s trademark arch appear on the windshield and rear window of his prize possession--a pristine red 1965 Mustang convertible.

A blueprint of the building, overlaid with a red heart, hangs in a hallway. It was a Valentine’s Day gift from the architects in 1982. “Len, We’re Yours,” they wrote, above an array of signatures. In his living room hangs a painted portrait of him, given by a commercial artist who labored on the center’s behalf.

When Bedsow joined the center in March, 1981, he knew it would be the last stop in his career. “He’s one of the best theater men I know,” said Bernard Jacobs, president of the Shubert Organization, Broadway’s most active producing company.

Bedsow first wanted to act, but World War II intervened. Joining the Army, he became a liaison to variety shows that toured the front. In liberated Paris, he said, he teamed up with Broadway director Joshua Logan to produce musicals for the Army.

Back home, he worked the theatrical gamut from stage manager to producer, hiring on with the Los Angeles operation of the Civic Light Opera in 1965. Rising after nine years to be general manager of its operations in Los Angeles and San Francisco, he took early retirement in 1980 and soon joined the Orange County center.

“I came in with a list of what I wanted to do, a bible of my intentions,” Bedsow said. “I wanted to use everything I had learned in this business.”

The Civic Light Opera had been a tenant of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, which Bedsow said he admired but sought to improve upon.

“I looked at the mistakes of the Chandler--the poor acoustics, the inadequate loading docks, too few rest rooms, the light color of walls in the auditorium, the shortage of backstage space.” He interviewed acousticians from throughout the United States whose professional reputations he was familiar with. Unfamiliar with Jerald Hyde and Dennis Paoletti, he heard them out anyway--then urged the board to hire them. Paoletti made an especially strong impression.

“Everybody else who came in was tired,” Bedsow said. “I felt at once that there wasn’t an ounce of creative energy in them. I was in my early 60s! I needed energy around me! Paoletti had energy.”

Paoletti and Hyde had formed a partnership with Harold Marshall, an acoustical pioneer who strongly influenced the Orange County theater’s design. “When I recommended them, I didn’t tell the board about Marshall’s concept,” Bedsow said. “I didn’t really understand it, and they wouldn’t have understood it either.”

(The concept, which produced a theater interior full of unusual tiers and angles, emphasizes enveloping the audience in reflections of sound.)

The acousticians said that Bedsow eventually grasped their ideas and conveyed them to his employers. He was fiercely possessive of that liaison role, as Marshall learned when he spoke directly to a board member about a model for testing the acoustics. Afterward, said people who were present, Bedsow lashed out at the acoustician. “He was shaking with anger,” Marshall said. “And it was a revelation to me that this was a breach, a real embarrassment, to talk to the client on a technical point.

“I saw he was walking this very fine line between these technical people on the one hand and these powerful egos . . . some very wealthy and powerful people . . . on the other.”

Bedsow became friendly with Charles Lawrence, the center’s lead architect. “He (Bedsow) gave us the strategic direction to do what we did and how we did it,” Lawrence said.

“He had a wonderful sense of showmanship,” Lawrence added. “In a certain sense, that kept the momentum up with the fund-raising.”

Bedsow told how he injected some high-tech dazzle into a fund-raising presentation whose original aim was to persuade a wealthy woman to donate $1 million to the center.

Shortly before the meeting, Bedsow learned that the woman’s husband would be there. Bedsow said he interrogated one of the center’s fund-raising consultants: “I asked, ‘What’s this guy’s background? Who is he?’ ”

The consultant recited the man’s particulars. He made computer parts. He was technically minded, liked to know how things worked. Bedsow recast his presentation.

“I focused more on the mechanical parts,” Bedsow said. “The acoustics. The electronic switchboard (to operate stage lighting). I really bulled on that because I didn’t believe in that. I think fast on my feet. . . . I could feel the guy melting.” The couple’s lawyer called the next day, Bedsow recalled. They would donate $4.25 million.

Bedsow virtually shouted as he remembered his grand design for who would perform at the center. “Perlman. Stern. Ashkenazy. Galway. I wanted biggies. Biggies!

“All this time, I was fending off the local groups,” he continued. “This place was not built for the Pacific Symphony,” he said. “It was not being built to be a facility for less-than-world-class organizations, and that’s what the local groups are.”

This point of view translated into a plan, which Bedsow says his employers endorsed, to cram the center’s prime dates with stars and toss locals the leftovers. Angered, the groups protested to sympathetic board members.

The leader of one local organization said that Bedsow played right into the hands of people who resented seeing an impresario from Los Angeles in charge of building a symbol to Orange County’s cultural independence. (Thomas R. Kendrick, Bedsow’s successor, former director of operations at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, has given the local groups more of a role.)

Meanwhile, Bedsow had other troubles. In January, 1984, a 45-year-old receptionist at the center’s former headquarters in a Costa Mesa bank building sued Bedsow and the center, alleging that she had “continuously refused and rejected” his sexual advances over four months ending in May, 1983. “It was an outright lie,” said Bedsow, of the allegations. “She was upset because she couldn’t have the job of executive secretary. When does a lie end?”

Neither Bedsow nor center officials would talk about what happened to the suit, which gave ammunition to Bedsow’s critics.

The case did not come to trial. The woman could not be reached for comment and her attorney has died. One source familiar with the matter, said the center settled the suit for an undisclosed amount. Bedsow said the timing of his departure in February, 1985, was planned. It was retirement, he says, plain and simple.

True, said former center President Rau, another executive director was to be hired by opening night. But Rau said that he had planned for Bedsow to become a consultant to the center until opening night. After Bedsow’s retirement in 1985, that never happened and Rau said bad feelings between Bedsow and the board were the reason.

“He wanted to become too much of a czar,” said Rau. “There is no question that this was to be the crowning achievement of his career. “He could have gone out in a blaze of glory and it would have been great.”

Center officials said that Bedsow will be invited, compliments of the house, to the opening-night benefit. Bedsow said Wednesday he hadn’t yet received the invitation, but would not go unless he felt sure he would not be snubbed.

“If other people are named for their contributions--the architect, the acousticians--then I want to be named too,” he said.

“The opening-night ceremony is in the process of being planned right now,” said Gary Hunt, chairman of the opening-night committee. “As for what is said and who is going to be involved, it’s just too early to say.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.