Castro Biography Paints Personal Portrait of Their Man in Havana

Ask almost any specialist on Latin America about the minimal attention that part of the world gets from most people in the United States, and he is likely to quote the North American newspaper editor who once sadly concluded that U.S. citizens “will do anything for Latin America except read about it.”

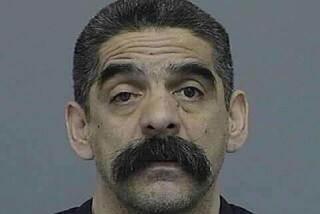

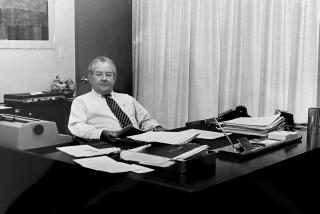

Tad Szulc has heard that phrase more often than most Latin Americanists. For one thing the 60-year-old author has been writing about the region longer than almost any other U.S. journalist, having first gone there as a foreign correspondent in the 1950s. For another, the former editor that saying is most often attributed to is James Reston of the New York Times, the newspaper for which Szulc labored in Latin America and elsewhere from 1953 until 1972.

Maybe that explains why Szulc remains so nonplussed in the face of the public attention and critical acclaim being given his latest book on Latin America, “Fidel: A Critical Portrait” (William Morrow & Co.: $19.95).

The book is the first biography of Cuban leader Fidel Castro to be written by a North American with Castro’s cooperation. It includes previously unknown details about Castro’s ideological conversion to communism, which Szulc concludes had occurred long before Castro publicly announced it in the early 1960s.

The book also reveals how Castro’s revolutionary organization, the 26th of July Movement, received money from the CIA during its campaign to overthrow then-Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista in the 1950s.

And it offers new insights from Castro on his tumultuous, and often dangerous, relationships with the United States, including the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban missile crisis of the following year.

“But let’s face it,” Szulc said. “I’m not Kitty Kelly and Fidel is not Frank Sinatra. The book may never be a best-seller, but I hope the attention will give it some appeal to the general public. It certainly has a chance. The reviews have been good, prominent and early. (“Fidel” was published Nov. 17 and has been featured on the front pages of the Los Angeles Times’ and New York Times’ book reviews).

There is even been talk about the biography being turned into a network television miniseries. Motion picture and television rights to “Fidel” have been sold to Jazbo Productions of Los Angeles, and when Szulc was in town recently to promote the book he met with Jazbo executives to discuss a six-hour script based on his 685-page tome.

Szulc refuses to get very excited about the prospects his book will get to television, but he does point out that a miniseries may be a useful way for many Americans to learn more about Castro the man, as opposed to the somewhat distorted symbol they often see in the media--a bearded, cigar-waving archenemy of the United States.

Americans think they know about Castro, Szulc said, simply because he has been around so long, causing so much trouble for seven presidents--from Dwight D. Eisenhower to Ronald Reagan--everywhere from Angola to Nicaragua. But the author said knowledge of the Cuban leader in this country is superficial, rarely getting below the surface of “an extremely fascinating personality.”

“The thing that struck me most when I began my research into the book was that there was almost nothing written about Castro’s formative years,” when the Cuban leader was growing up in a middle-class farm family in Cuba’s Oriente province. “That’s why I decided to write a biography about Castro rather than one more history of the Cuban revolution. I hoped, through that format, to make my readers understand what makes a man like him, and other people like him in Nicaragua and other Latin American countries, act the way they do.

An Important Figure

“Whether you like him or not, Castro is still an enormously important and powerful figure in Latin America and, to a lesser extent, the rest of the Third World. If we are to deal with him, and other people like him, we have to know them better and at least try to understand what motivates them.”

Americans must realize, Szulc said, that the hostile attitude Castro and other leftist Latin Americans, like Nicaragua’s Sandinistas, have toward the United States is not just a knee-jerk reaction resulting from their Marxist politics or sympathies for the Soviet Union. Latin American enmity for the proverbial “Colossus of the North” also stems from nationalism and “is not as irrational as it might seem to us in the United States,” he said.

Repeatedly in his book, for example, Szulc points out how the young Castro was influenced by Cuban patriot Jose Marti long before he was exposed to Marx and Lenin. It was Marti who launched Cuba’s final war for independence from Spain in 1895, and his untimely death early in that struggle made him the most revered martyr in Cuban history. Like other Latin American nationalists of his time, Marti was highly suspicious of the United States and the expansionist designs many North Americans had on the region during that era of Manifest Destiny.

Marti’s fear of the United States seemed to be borne out after the United States went to war with Spain in 1898--while the Cuban war for independence still raged--and occupied several Spanish colonies, including Cuba and Puerto Rico after the U.S. victory.

Although Cuba was granted independence shortly afterward, the United States remained a dominant influence on the island for several more generations. The most hated symbol of that era was the Platt Amendment to the Cuban Constitution of 1902. Inserted at the insistence of the United States, the amendment gave the United States a unilateral right to intervene in Cuban affairs whenever it was deemed necessary. U.S. Marines were landed on the island several times early in this century, using the Platt Amendment as justification.

The amendment was revoked in 1934, as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy, but it remains a hated symbol of Yankee dominance over Cuba to Castro and other Cubans of his generation, according to Szulc.

Adding to the United States’ negative image in Cuba is the fact that U.S. companies were deeply involved in the nation’s economy for many years. In the farming region where Castro grew up, Szulc said, the United Fruit Co. had the greatest influence. And while United Fruit provided housing, schools and other benefits for its North American employees in Cuba, and their families, many of their Cuban employees lived in poverty and squalor. “This was the social environment that Fidel Castro remembers from his childhood,” Szulc said, “and it awakened him politically as he matured.”

Behind the Revolution

Cuba’s humiliating relationship with the United States would last, for all intents and purposes, until Castro came to power in 1959. And Szulc argues that Castro’s decision to align himself with the Soviet Bloc after the revolution was initially motivated less by Castro’s conversion to Marxist politics than it was by his fear that, without support from an outside power, the Cuban revolution could be undermined by U.S. influence the same way Marti’s war for independence had been 60 years earlier.

Szulc’s personal acquaintance with Castro dates from 1959, when he was first sent by the New York Times to cover the aftermath of Castro’s triumph.

A native of Warsaw, Szulc was introduced to the young Cuban guerrilla leader by Herbert Matthews, the New York Times editorial writer who had first made Castro famous outside Cuba. It was Matthews who wrote a series of articles on Castro for the Times in 1958, based on interviews he conducted with Castro in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains, the base of his guerrilla war against the Batista government.

Szulc speaks fluent Spanish, and his first meeting with Castro was highlighted by an all-night conversation that began in the Havana Libre Hotel (formerly the Havana Hilton) and ended at 4 a.m. on a nearby beach. Szulc filed many stories from Cuba in the next couple of years, and even got a private tour of the Bay of Pigs battlefield from Castro shortly after that CIA-sponsored invasion by Cuban exiles failed.

Szulc left Latin America shortly afterward, but remained a student of what he and Cubans call Fidelismo from afar, particularly after the Cuban leader played a key role in the world’s closest brush so far with a nuclear confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union: the crisis of October, 1962, when President John F. Kennedy pressured Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev into withdrawing medium-range nuclear missiles that the Soviets had based on the island with Castro’s acquiescence.

Szulc did not come into regular contact with the Cuban leader again until 1984 when he returned to Cuba as a free-lance writer to prepare a profile of Castro for Parade magazine. One of the first things Szulc discovered is that the Cuban leader had not lost his penchant for long conversations. The author recalled that their first session began at 1 a.m. and lasted nine hours.

A Weekend Visit

Szulc wound up spending the better part of a weekend with Castro on that visit. At the end of it, the author off-handedly proposed to Castro that he write a biography of him. “The idea of writing a book about Fidel had not crossed my mind until just before I asked him,” Szulc said.

To Szulc’s surprise, the Cuban leader agreed to cooperate almost immediately. Szulc returned to Cuba early in 1985 and rented a home near Havana where he and his wife lived for almost a year while he researched the book.

To Szulc’s delight, Castro not only cooperated with him, but ordered Cuban government officials and files be at the author’s disposal. The author said many of those officials provided insights into Castro’s life and political development, particularly those Cubans who had been acquaintances of Castro’s since his days as a guerrilla fighter. Szulc said that helped focus his book more on Castro’s life and personality rather than on rehashing well-known incidents like the missile crisis or the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Szulc also said it was easy to focus the book on Castro’s youth and early politics because the Cuban leader has changed little since the early 1970s.

That theme is the most critical in Szulc’s portrait of Castro. The author argues that the once-dynamic Cuban leader has simply run out of fresh ideas. And while there has been no official reaction from the Cuban government to Szulc’s book so far, the author has heard indirectly that this theme has angered Cuban officials.

“Their reaction is something like: ‘How dare he say that Fidel has no new ideas?’ ” Szulc said. “Castro seems blithely unaware that he has become almost passe in Latin America.” (Szulc said he doesn’t know if Castro has read the book.)

“That is not to say he is not an enormously important and powerful figure,” Szulc said, “but people are looking at him more critically then ever before. They look at the Cuban model of development, and are rejecting it.”

“Castro has missed out on the realization that the great debate over development in the Third World is no longer Communism versus capitalism. It is between nations with free-market economies and nations whose economies are centrally planned by government.”

Economic Failures

Castro’s Cuba is a classic illustration of a centrally planned economy, Szulc said. And it has been a consistent failure in recent years.

Despite the significant early achievements of the Cuban revolution, which brought literacy, health care and a better standard of living to the majority of the island’s people, Szulc said that in recent years the Cuban system has been stultified by several problems, including a continued dependence on Soviet economic aid, a large, increasingly corrupt and inefficient Communist Party bureaucracy, and Castro’s personal unwillingness to surrender authority over the smallest details of his government to anyone else.

“Recently Castro has sponsored a series of meetings on the Latin American debt problem,” Szulc said. “He invited leaders from throughout the region to discuss the issue in Havana, and he wound up sitting through hour after hour of speeches about it. He never left those meetings, and while he was there almost nothing else was done in Cuba.”

While living in Cuba, Szulc also sensed that young people on the island, those Cubans born in the years since the revolution, now take its achievements for granted. Szulc believes Castro wants these Cubans to recapture the fervor of the revolution’s early days, and is increasingly frustrated at his failure to get them do so. Castro’s latest speeches are angry in tone, Szulc said, denouncing the evils of materialism (black marketeering is a serious problem in modern Cuba), the high rate of absenteeism and low productivity, and the bourgeoisie pretensions of “rich” peasants and dissatisfied intellectuals.

So has the Cuban Revolution run its course? Not as long as Castro the man remains, Szulc said. Castro is still immensely popular with the Cuban people, and they are unlikely to turn against him, and the revolution he helped bring about, as long as he remains alive. And the 60-year-old Cuban leader is, by all accounts, in good health.

“He will be around a good while longer,” Szulc said, “but that does not mean that we should not start thinking of how we should deal with Cuba after Fidel.”

No Changes Soon

Szulc believes Castro’s relations with the United States have been so difficult over the years, and especially under the Reagan Administration, that there is no point in trying to change things in the immediate future. “Not much can be done now, given Fidel’s attitudes towards the United States, and vice versa.

“But there will have to be changes after Castro dies. The Cuban Revolution has always been, first and foremost, Fidelista, and I just don’t see anyone being able to hold it together in the same way after he is gone, even Raul Castro (the dictator’s brother and defense minister, who was officially named heir apparent at a recent Cuban Communist Party congress).”

“When that transition comes, it will be an opportunity for a new era in U.S.-Cuban relations,” Szulc said. “I hope by then our government’s leaders will show more creativity in dealing with Cuba than they have in the past, or than they are showing even today.”

“Radio Marti is not a creative policy,” Szulc said, dismissing the news and propaganda programs the Reagan Administration recently began broadcasting to Cuba. “It is just one more reaction to Castro. That’s what U.S. governments have been doing with Castro and Cuba for almost 30 years now--reacting.”

Even the Kennedy Administration’s Alliance for Progress, through which the United States helped push for social and economic reforms in Latin America, came about as a reaction to the Cuban Revolution, Szulc said. “That is why policy-makers in this country must learn more about Latin America--so they can do more than just react when a fire breaks out.

“Sometimes I feel like I’ve been writing and saying the same thing for 30 years, too. When will responsible people in this country give Latin America the attention it deserves? And not just Cuba or Nicaragua, but Mexico and the rest of the region?

“I’d like to think that if my Castro book is successful with general readers, that it might help bring such a change about.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.