MARK TAPER TWENTY : SHADES OF GRAY DUE AT THE TAPER

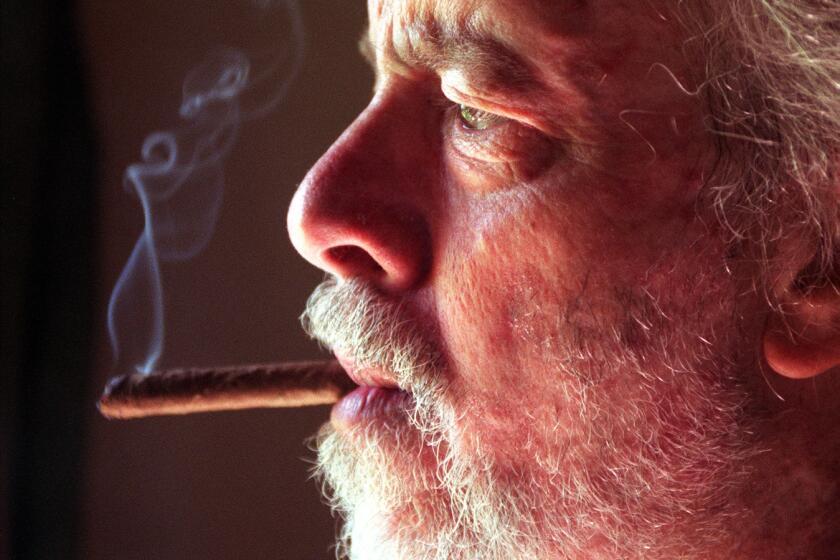

Spalding Gray, with the start of a salt-and-pepper beard growth, sat at a little dining room table covered by a “State of California” tablecloth--the kind tourists might buy. He was talking about himself again.

“The thing I’ve come to know about myself now is that I don’t have an acting career. I mean I do act,” he said, reminding his visitor that at 5 the next morning he was flying to Georgia to act in Pat (Cal) O’Connor’s new film, “Stars and Bars.”

“The monologues are the real work I do, which is a special kind of acting . . . playing myself. There’s no one else in the U.S. that I know of doing what I do. There’s also no one else I know of with the name Spalding (his brothers’ names are Channing and Rockwell). And when I was growing up in Barrington, R.I., there was only one other kid who went to Christian Science Sunday school. So I’ve always felt like this odd creature, a little outside.”

This 45-year-old, self-described displaced New Englander, monologuist, writer and reluctant actor was thinking less about himself, though, than about the new film of his best-known monologue, “Swimming to Cambodia,” wherein Gray recounts his epiphanic experiences working on “The Killing Fields.”

The “Cambodia” film, transferred to the screen with crafty condensation by Gray, his screenwriter girlfriend, Renee Shafransky (who also produced the film), and director Jonathan Demme, holds special meaning for those who saw his performance of the piece at Taper, Too.

Gray is tying that connection together at 8 p.m. Wednesday with “A Personal History of the Mark Taper Forum,” to be spontaneously devised on the Taper main stage as part of that theater’s 20th anniversary week. Serendipity, he asserts, is his life’s guiding principle. It extends to his plans for this impromptu Taper performance.

“I’ll arrive at the Taper an hour beforehand,” he said, “pick out people in the lobby who intuitively interest me and ask them their feelings about the Taper, such as why they go there in the first place. They’ll be part of the performance, and I’ll do a monologue on whatever is on my mind at the moment.”

When is it time to do a monologue?

“It’s intuitive. There’s a logjam of information that piles up and makes a pattern. Certain incidents refer to other incidents, a theme gradually emerges. I never look for it, though. But I’m constantly recording, observing, telling stories.

“Of all my monologues to be filmed, (“Cambodia”) was the most appropriate, since it’s a monologue about a film. So it comes back in a wonderful full circle,” he said, sitting in the rented Silver Lake home that had been D. W. Griffith’s office during the making of “Birth of a Nation.”

“I say this half in jest, but the perfect thing now would be for clips from ‘Swimming,’ such as the history of Cambodia, to be inserted into ‘The Killing Fields.’ But then, I like things to reflect each other.

“I had just finished a long run (of “Swimming to Cambodia”) at Lincoln Center and three months in Australia, so I needed to get thrown off by something to freshen up the performance,” which is what Demme’s distracting cameras did. “I finally got to know the camera, and got rid of that . . . guilt, which is what I felt leaving my live audience behind for the first time.”

Yes, Gray confesses--with that soft, ironic charm that invariably seduces his listener--he would have made a good Catholic when it comes to a propensity for guilt. But his mother’s devotion to Christian Science is what held sway in Rhode Island, where he began growing up “like a regular kid, and then, all of a sudden, I was told I was a ‘slow learner.’ What I had was dyslexia, but no one knew that then.

“I repeated several grades, became a juvenile delinquent (nothing more serious than tossing Campbell’s soup over balconies) and didn’t graduate high school until I was 21.” That was the year he discovered the stage, acting in a school play.

Gray acknowledged that Christian Science’s demanding metaphysics has had a lasting effect, and not only from the wake left by his mother’s suicide in 1967.

“In that religion, to name the disease is to give power to it. I think I’ve reversed that in my work: To name it is to heal it. That’s how my monologues are therapeutic.”

A week later, on Gray’s return from his acting stint in “Stars and Bars,” he reported that he’d begun his oft-delayed novel, “Impossible Vacation,” between camera setups. Predictably, he talked again about his travels.

“You could call me a travel writer (last year he wandered in Bali; this year he and Shafransky are headed for the Soviet Union and Nicaragua). I’m very affected by the place I’m in. I go somewhere, become receptive to it, and then begin to record it in writing.”

Listeners assume that Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac, those other peripatetic diarists, are Gray’s primary influences. But he stressed the sway Thomas Wolfe has had over him.

“People think I’m solipsistic and self-obsessed, but all I’m talking about are things in my life that are larger than me.”

Gray’s view of his own experimentalism casts avant-garde notions in a new light.

“What I’m doing is a very traditional oral novel,” he explained. “It’s experimental because I’m taking complete responsibility in the form of direct address. Wolfe would hide behind the printed word, or slightly disguised characters.”

Where does the reporter end and the performer begin?

“When I’ve pretty much netted in the information I think I need,” he said.

“The performing starts when I sit down at my desk on stage.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.