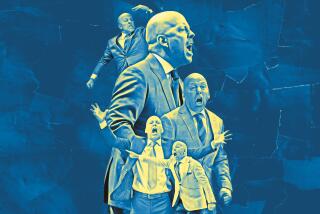

BOB FOERSTER’S BATTLE : Former Cerritos Coach Leaves Hustle of College Basketball, Bustle of City for Quiet River to Recover From Rare Paralysis

COLOMA — Bob Foerster lifted himself slowly out of a lounge chair and to his feet. He extended an open hand to a visitor and asked for help in standing.

“It takes me some time to get going,” he said, taking the visitor’s right hand in his while clinging to the back of the chair. “I’m trying to learn to walk without my braces.”

Men once sought fortunes in the gold country here. They searched along the twisting banks of the American River, groping for the precious substance that could change their lives.

Five months ago Foerster moved here, half a mile downstream from Sutter’s Mill, to pan out his future. The former basketball coach at Cerritos College is battling the effects of Guillain-Barre Syndrome, a rare affliction that temporarily paralyzes its victims. Although most patients recover in a relatively short period, Foerster remains handicapped. His struggle has lasted more than five years.

He was one of the more severe patients we’ve had,” said Dr. Harry L. Gibson of St. Jude Hospital in Fullerton. “The percentage of cases like Mr. Foerster is low, but they are there.”

The legs that once carried Foerster on his fiery walks up and down the court, now go numb when he sits. He cannot put on his own socks because he can’t reach that far. He has very little muscle tone below the knee. A 200-foot walk from his porch to the river’s edge is a two-hour trip with a cane.

At 55, he has forsaken his native Southern California and with it a chunk of his past. He says he moved here to escape the hustle and bustle of his sprawling suburban life style, but his move may have been advanced by a series of personal dilemmas.

A year into his hospitalization, an already shaky marriage collapsed. His return as a physical education instructor at Cerritos College disappointed him when he found it impractical to teach tennis in a wheelchair and be an assistant women’s basketball coach in a walker. He took a sabbatical leave, traveled the country and then decided not to return to his job.

“A recluse? Yes, some people have said that about me,” he admited. But he said he has accepted his affliction as a blessing.

“Guillain-Barre gave me the opportunity to change my life.”

Dressed in nylon sweats, polo shirt and tennis shoes, he still looks like a coach. But with the bushy salt-and-pepper beard, he could be a mountain man. He exudes the cagey intelligence of the old Foerster when he speaks, but his mannerisms suggest that he is adjusting to a new way of life.

Nevertheless, he is more than cordial with old acquaintances. He entertains selected people from Southern California, often inviting them to spend days in his home. He writes “about 10 letters a day,” and a favorite trip in his faded green 1970 Ford pickup is down to the one-room post office on the town’s main street to meet the 3 p.m. mail.

“I miss coaching. I miss my friends, but I enjoy what I have now more,” he said, running an index finger over his beard. His other contacts with the outside world are a telephone and a TV satellite dish, on which he receives sporting events from around the country.

“We don’t miss Southern California,” said Sandy Verner, Foerster’s girlfriend, a pretty woman in her 40s with shoulder-length brownish-gray hair and bright green eyes.

Known as Stern Taskmaster

As a coach, Foerster was respected, first on the prep level at Bellflower High School and later in the two-year ranks at Cerritos. In 13 years with the Falcons, he posted a 224-131 won-lost record. He also was known as a stern taskmaster, a philosophy, he said, he adopted in high school as a tennis and basketball player.

“I didn’t know how to do things in coaching without putting in a lot of time.” he said. “We would work every damn day. I didn’t know any other way to get success out of people other than that.”

At the time of his illness, in the spring of 1982, he was assembling a basketball team that would later win the state title as he lay paralyzed in a hospital bed. The lost opportunity sometimes haunts him, he said.

Twice before he had taken the Falcons to the championship game of the California community college basketball tournament only to be defeated. He intended to overcome that with the team he was building in 1982.

“It was obviously destined for that team to win the state title,” he said. “Not being able to coach, it is a hard thing to come to grips with, but maybe that was for the best. My mind has been on (my) recovery, but I still think about that team quite a bit.”

Jack Bogdanovich, a longtime Cerritos assistant, was appointed head coach soon after Foerster became ill. Cerritos has since won five South Coast Conference titles, in addition to the state title. The Falcons have been routinely ranked among the top five community colleges in the state the past five seasons.

Once close friends, Foerster and Bogdanovich do not speak to each other anymore. Foerster refuses to discuss the estranged relationship, except to say that “a definite rift exists.”

Said Bogdanovich, who stood by Foerster’s bedside daily in the first three months of his ailment: “I was like a brother to him. It’s a tough situation. Bob has always been very hard on people that are the closest to him. I was there all the time he needed me the most. I guess that was hard for him to take.”

Time, Foerster said, has the ability to change everything.

“After a divorce, you don’t run with the same crowd anymore. Sickness is like that. Along the way you lose some people and you pick up some people, too.”

Foerster and Verner live in a quiet, rustic home at the end of a one-lane, winding dirt road in a sparsely populated valley. An occasional white-water raft passes through the rapids and heads downstream along the South Fork of the American River, which runs through their property. Verner, a nurse, is studying to be a river guide. Foerster has ridden the rapids a couple of times.

On a wood-plank porch awash in swirling petals from nearby dogwood trees, a thermometer that reads “Dri-Power” pushes the 100-degree mark as they discuss their lives together. The thermometer is one of many collectibles they refurbish and sell along with restored antiques for extra cash to supplement Foerster’s monthly disability checks.

The couple had their first date when Foerster was still in a wheelchair, 18 months after he contracted the disease. They had known each other casually through friends for years.

“We plan to get married when my divorce is final,” he said.

Foerster is not sure he will regain the mobility he once had. He needs assistance in walking, often clinging to furniture or railings. His handshake, swollen by gnarled fingers, is not what it once was. Only in the last few months has he been able to hold a bottle of beer in a single hand.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever be what you call normal again,” he said.

But there is no pain. Guillain-Barre, which attacks the lining around nerves and interrupts electric impulses from the brain, is a painless disease. It does not attack the brain, although the physical disabilities often suggest the appearance of brain damage.

“(People) treat you as though not only your body, but your mind is affected, too,” he said. “Things like that happen all the time and you become very self-conscious about it.”

Foerster was in a run-down condition from a bad case of the flu that fateful day in 1982 when he caught himself stumbling while teaching a nighttime tennis class. He needed two hands to turn the key on the ignition of his truck for the 10-mile ride home. He staggered into his Rossmoor home and dropped into bed. The next morning he awoke paralyzed.

He spent 3 1/2 months on life-support systems in an intensive-care room and another 15 months in a hospital rehabilitation ward. He lost 80 pounds. He could not talk for months and did not walk for three years. When he finally got on his feet he required braces and later, a walker.

He has fallen numerous times because balance is difficult. He broke his left leg in the hospital. At home, he broke a wrist. When he returned to Cerritos College he was knocked over several times in crowded walkways. Eight weeks ago while on a walk here he took a bad fall on his right leg, but suffered only bruises.

“I have to be careful,” he said.

Which is the way he wants to approach his life in this new environment, knowing that he may never regain what he once had.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.