Love Is the Heart of Everything CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN VLADIMIR MAYAKOVSKY AND LILI BRIK, 1915-1930<i> edited by Bengt Jangfeldt; translated by Julian Graffy (Grove: $18.95; 294 pp.)</i>

- Share via

Does the world really need this book? 416 effusive letters, notes, post cards, and telegrams that don’t so much chronicle the passionate liaison between Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930) and Lili Brik (1891-1978) as testify, like the wreckage after a tornado, to its stormy excess. Julian Graffy’s translation is generally deft, and Bengt Jangfeldt’s editing as learned and detailed as one could wish. But the Swedish professor’s claim that “Mayakovsky and Brik “are one of the most remarkable pairs of lovers in the history of world literature” calls for more than these artless--though admittedly live--documents to validate it.

Mayakovsky (who in 1935 was posthumously immortalized by Stalin as “the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch”) first met Lili Brik and became her lover in 1915. A beautiful dilettante (would-be film actress, sculptor, dancer) and intellectual hostess, she was in charge of the affair from the beginning; and many people, including the poet’s mother, Alexandra Andreyevna, believed he would not have killed himself, had Lili not been absent. In any case, her husband, Osip, complacently seconded their relationship (the Briks had given up sleeping together several years before), which lasted until 1925 despite a number of infidelities on both sides (and an illegitimate daughter casually fathered by Mayakovsky during a brief stay in America). Thereafter, the lovers remained the closest of friends until Mayakovsky put a bullet through his heart in 1930. Mayakovsky had many reasons for committing suicide: He was still hurting from his break-up with Lili; his hoped-for marriage with Tatyana Yakovleva had come to nothing; his affair with the young actress Nora Polonskaya was in trouble; his work 2002875168fracturing her hip and depressed by assaults from Soviet literary apparatchiki, killed herself with an overdose of sleeping pills.

Mayakovsky’s talent was great enough to survive Stalin’s endorsement, but the role played in his life by the Briks has always been somewhat obscure. Since the early 1970s, the Soviets have been trying to erase or denigrate the memory of Osip and Lily Brik, who symbolize various things--Futurism, bohemianism, “moral adventurism,” and Jewishness--that might threaten Mayakovsky’s reputation of unblemished communist orthodoxy. Readers can consult the one full-dress account of the Mayakovsky-Brik affair, Ann and Samuel Charters’ “I Love” (1979); but, except for some two dozen marvelous photographs, this is a mediocre, unreliable pop biography, handicapped by what Jangfeldt too vehemently denounces as its authors’ “complete ignorance of the Russian language and of Russian literature.” Jangfeldt’s 35-page introduction to the correspondence is a major contribution to our knowledge of Mayakovsky, but there is much he doesn’t tell, and the letters themselves are in many ways uninformative. For example, we have to go to the Charters for the noteworthy fact--presumably supplied by either Brik or her friend Rita Rait--that Brik never had a “satisfying physical relationship” with any man until 1929, when she met the civil war hero, Gen. Vitaly Primakov, whom she married two years later. (He was shot in 1937 during the purge of the Red Army.)

But, though we don’t have anything like the full story, we may already have enough. Certainly the letters give us a clear and powerful impression of the hulking, boisterous (when not sullen), volatile, imposing Mayakovsky, a man fairly bursting with energy and sexual magnetism. We see his characteristic childlike adoration of animals--calling himself “Shchen” (“puppy”), after the rather large mongrel of that name he shared as a pet with the Briks, and often closing his letters with Thurberesque drawings of himself as a dog. The more worldly, conventional, and (despite all the exclamation points) controlled Brik (who signed her letters with the sketch of a small cat) makes a less striking figure.

The pair seem to have only two registers, the ecstatic-babbling (“I kiss you! My dears! My beloved ones! My own ones! Lights of my life! My little suns! My little Kittens! My little puppies! Love me! Don’t betray me! If you do I’ll tear off all your paws!” L. B. to V. M. and O. B.; “Liska, Lichika, Luchik, Lilyonok, Lasochka, Lapochka, Little child, Little sun, Little comet, Little star, Little child, Sweet chi1818504224B.) and the wholly mundane (“Why hasn’t Olga Vladimirovna received the parcel from Alter sent at the same time as the parcels for Osya and Lyova, which they have received? Find out what’s up” L. B. to V. M.). But they say disappointingly little about their deeper feelings for each other.

Mayakovsky is more forthcoming than Brik on this score, but his passion, even at its most intense, has an abstract quality about it. “Love is my life,” he writes to his mistress, “love is the main thing. My poetry, my actions, everything else stems from it. Love is the heart of everything. If it stops working, all the rest withers, becomes superfluous, unnecessary.” Such love sounds more like an organic drive, however violent, than a personal connection. And for her part, Brik seems, perhaps understandably, to have cared more for Mayakovsky the poet than for Mayakovsky the man. “Volodya didn’t simply fall in love with me,” she later reminisced, in a half-boasting, half-vexed tone, “He attacked me, I was under attack. For two and a half years, I didn’t have a single minute’s peace--literally.”

Was this story worth rescuing from oblivion? Broadly speaking, yes. Brik and Mayakovsky’s “puppy love” was short on style and clearly not intended for publication, yet highly public and theatrical (there is not an embarrassingly intimate line in the whole collection). It seems these lovers meant to be overheard, and now they have been. Pace Jangfeldt, we will not have to expand the canon of the world’s great love letters to include those published here. But we may well find their writers a memorable couple.

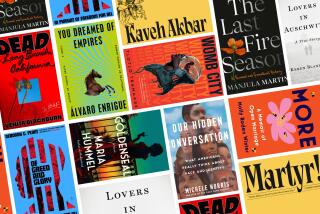

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.