Sour Notes Heard in the Musicians Union

After 30 years of relative harmony, the American Federation of Musicians is once more torn by a furious internal battle.

And once again the battle is over the leadership of an AFM president and a multimillion-dollar trust fund that funnels record royalties to musicians and finances free concerts across the nation for schools and charities.

The union and its officers have had a profound effect, almost entirely beneficial, on music and musicians in this country since the AFM was formed 91 years ago.

But when musicians have open battles in their union, they create a real cacophony.

In broader terms, their current fight, like the one 30 years ago, seems to demonstrate anew that entrenched, heavy-handed union leaders can be tossed out by the members. But the members can do that only if they make use of the democratic system available to them under their union constitutions and federal law.

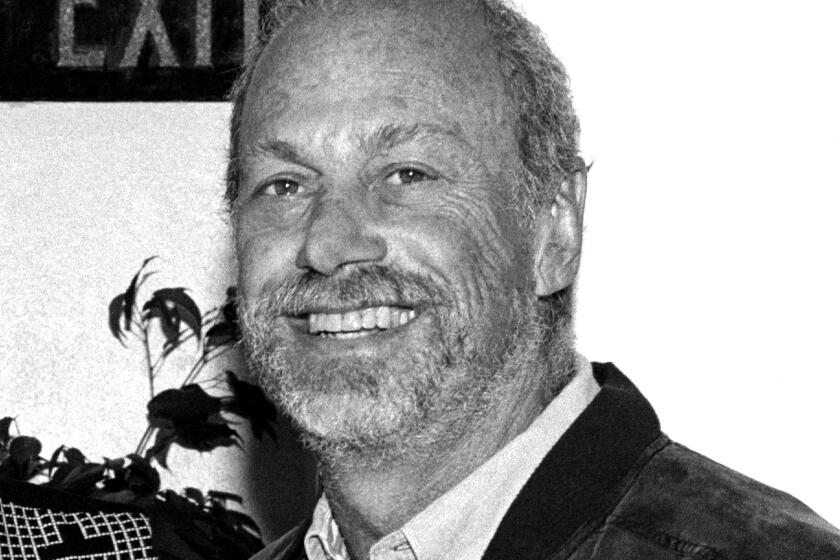

There has been no hint of corruption or of ties with the underworld in either the AFM’s leadership struggle today or the one in 1956-57, when there was a rebellion against James C. Petrillo, the AFM president who made major gains for musicians but whose authoritarian style earned him the nickname “Little Caesar.”

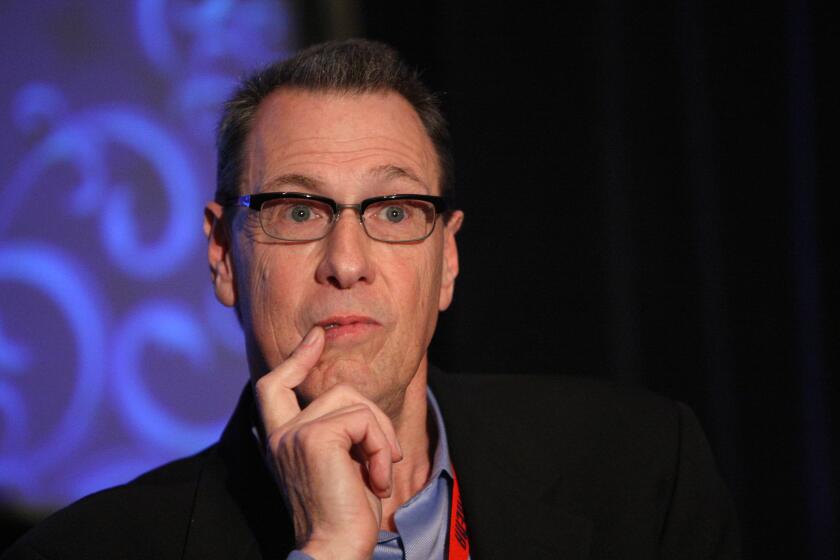

The current fight inside the AFM didn’t end with its first contested presidential election on June 19 at the union’s convention in Las Vegas, in which J. Martin Emerson defeated incumbent AFM President Victor Fuentealba. On Friday, the defiant Fuentealba issued a call for a special meeting on Aug. 3 of the union’s old executive board to try to get support for his demand that the government void the election results.

Fuentealba complains that leaders of the major AFM locals in Los Angeles, New York, Chicago and Nashville used undue and illegal influence at last month’s convention to defeat him, a charge that will be hard to substantiate.

Nevertheless, the defeated AFM president wants the government to order a nationwide referendum to allow all members to vote in a mail ballot election.

Fuentealba may figure that he will have a better shot at victory in a nationwide referendum in which all members would vote, not just delegates to the national convention. This means he could appeal to the vast majority of the union’s members who don’t make their living as musicians and so don’t always pay much attention to internal union affairs.

Part-time musicians are less likely to have heard much about accusations against Fuentealba, including one that he made major, unnecessary concessions in recent contract negotiations with the highly profitable recording industry. Delegates at the recent convention, on the other hand, talked constantly about the complaints against him.

Critics said Fuentealba negotiated a pact that substantially reduced trust fund contributions from the industry, thus cutting both recording royalty payments to musicians and funds for free concerts.

The cuts seem unfortunate because these funds have paid for free concerts that have helped people develop an appreciation of live music. The trust fund money goes to musicians who perform at the concerts.

But reductions in trust fund contributions may not be a hot issue with the part-time musicians.

Fuentealba did negotiate pay raises of about 5% a year over the next three years, but his opponents say that, too, was not a bright move.

Concerned that they might price themselves out of the recording market, critics argue that musicians’ pay is not unduly low. They now get more than $200 in wages and benefits for a three-hour recording session, and if their wages go up much further, companies seeking cheap musicians might move more production abroad or to non-union companies.

In contrast, trust fund contributions are based on actual record sales and so don’t affect initial production costs.

The battle against the outgoing AFM president is thus based on musicians’ support for the trust fund. Ironically, the earlier intra-union battle in 1956-57 was based on musicians’ resentment of Petrillo for negotiating the innovative trust fund.

Musicians were unhappy because fund contributions took money out of their paychecks. That continued until Petrillo’s successor, Herman Kenin, won a pact that divided recording royalties, so that half would go to musicians directly and the other half would pay musicians for performing at free concerts.

That fight against an incumbent president 30 years ago was far more difficult than this year’s. The current president-elect, Marty Emerson, 74, has been the AFM national secretary-treasurer for 10 years and has the support of the union’s big-city locals.

It was different in 1956, when a few unknown rebels in Los Angeles AFM Local 47 mounted the challenge to Petrillo, then one of America’s best-known union chiefs.

He had defied President Roosevelt by calling a strike during World War II to protest the displacement of musicians by recorded music. He battled against entertainment industry moguls and mobsters during his 18 years as AFM president. And so, naturally, he was initially contemptuous of those upstart Los Angeles rebels led by a trumpeter named Cecil Read.

But in the long run, the rebels won. They created a rival union that won residual payments for musicians, a first in the entertainment industry.

In 1958, just two years after they began fighting his dictatorial leadership, Petrillo resigned the presidency and the rival union was dissolved. (But members also lost the residuals that most other film and television industry employees now enjoy when their performances are repeated.)

“I am tired, and the union should have new leaders,” Petrillo said, returning to his Chicago local. Four years later, he was beaten for reelection. He died on Oct. 23, 1984, at age 94.

Succeeding international presidents also improved the union and the economic lives of musicians.

Fuentealba, too, was highly regarded during most of his 10 years in office--until he seemed to feel that he, like Little Caesar, could be a one-man show.

Workers as Buyers

Most studies of America’s troubles in international economic competition focus on how much it costs companies in various nations to make a product.

Unfortunately, the researchers don’t spend much time estimating the benefits workers get for making the products.

But a key to economic development is the ability of workers to buy what they produce, says Herman Rebhan, general secretary of the Geneva-based International Metal Workers’ Federation.

A new study by the federation shows huge gaps in worker purchasing power around the world.

In general, workers in America’s highly unionized auto, steel and other metals industries are able to buy more with their wages than those in any other country.

For example, an American worker who builds refrigerators must work 25 hours to buy one; it takes 67 hours for an Italian worker, 83 hours for a French worker and 410 hours for a Chilean worker.

In India, a worker has to toil 997 hours to buy the refrigerator he helps make, or almost 40 times more than the American.

Among auto workers, there also are huge gaps. An American auto maker must work 753 hours to buy a car, compared to 1,318 hours in Britain, 1,545 hours in Spain, 1,781 hours in Australia and 1,922 hours in France. In Japan, however, an auto worker has to work only 541 hours to pay for the car.

But because getting cheap labor almost always is the name of the corporate game, companies frequently go to underdeveloped countries.

Mitsubishi, which is partly owned by Chrysler, has built a car plant in Malaysia in cooperation with that country’s government. Mitsubishi/Chrysler workers in Malaysia have to work 7,143 hours, or nearly 10 times longer than their Japanese counterparts, to buy the cars they make.

It will a long time, if at all, before workers in highly industrialized and underdeveloped nations have comparable incomes. But surely fair international trade policies have to take into consideration the need for workers to buy the products they make.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.