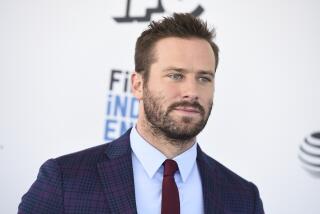

Woody Herman Dies at 74 After Half Century of Making Swing Music

- Share via

Woody Herman, who prevailed for decades as a top swing band leader only to become in his final days a sad figure overwhelmed by debilitating illness and a crushing debt to the federal government, died Thursday afternoon.

He was 74 and died at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center where he had been since Oct. 1, suffering from congestive heart failure, emphysema and pneumonia. The famed clarinetist and jazz innovator had been on a life-support system.

Fans of the man who since the 1940s had led a succession of “Herds” romping through such swinging numbers as “Woodchoppers Ball” learned in early September that the bandleader was bedridden, behind on his rent and about to be evicted from the Hollywood Hills home he and his late wife, Charlotte, bought from Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in the ‘40s.

IRS Seized Home

The Hermans lived there for more than 40 years until the Internal Revenue Service seized the home and later sold it for nonpayment of $1.6 million in back taxes.

Herman’s daughter, Ingrid Herman Reese, said her father’s financial problems began in the mid-1960s, when a business manager failed to withhold payroll taxes for three years. Herman also contended that the IRS incorrectly figured what he owed from the 1940s, when he earned an estimated $1 million a year.

News of Herman’s plight brought help from jazz radio stations and fans as well as from such celebrities as Frank Sinatra and Clint Eastwood. The back rent was paid to the man who had bought the house from the IRS and Herman was allowed to remain there.

Donations could approximate $140,000 by the time all funds have been received, said his attorney, Kirk Pasich, shortly after learning of Herman’s death.

Pasich also said there still is legislation pending in Congress to forgive the bandleader’s tax debts, but he added that the death may have rendered that moot.

To have evicted Herman, Pasich had said in early September, would have killed him.

‘Boy Wonder’

No one who saw the bandleader at the time thought that he would live much longer in any event.

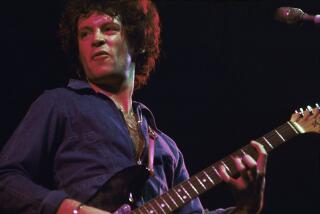

Woodrow Charles Herman, Milwaukee-born son of vaudevillians, was a singing, tap-dancing “boy wonder” on stage at 6. He gained fame in the late 1930s with “The Band That Plays the Blues,” then went on to head a series of Herman “Herds” consisting of young, technically skilled musicians.

His clarinet and saxophone and his amiable singing remained his trademarks as he progressed from the blues to an intense, driving swing style--and as he took one financially disastrous be-bop flyer during the late ‘40s.

In 1981, when had been a road-traveling bandleader for 45 years, Herman told an interviewer, “I would never play down to an audience. In other words, let them come find us. . . .”

Generally, they did.

Enough so that in 1986, when he appeared in a Hollywood Bowl concert at age 73 to celebrate 50 years in the band business, he was able to say, “I’m a happy old man still on the road because I dig what I’m doing. And as long as I have a band that I think plays very well, I’m quite contented and happy.”

That, he said, was “because I’m doing what I like best to do best, and I feel that the Lord’s given me a fair shot. He’s allowed me to live all this time.”

It was out of his own earnings as a child in vaudeville that Herman bought a saxophone and then a clarinet. He learned to play them and finally got a job with a Milwaukee area roadhouse band.

At 16, after earning $70 a week playing nights in a ballroom while going to high school, Herman was hired by bandleader Tom Gerun in California.

After jobs with the bands of Harry Sosnik and Gus Arnheim, Herman joined the well-known Isham Jones band in 1934.

When Jones decided in 1936 to retire because of ill health, Herman and several other key members formed a cooperative orchestra in which all owned stock. Herman was the leader because of his show-business personality.

It was billed as “The Band That Plays the Blues,” and it had a hard time keeping bookings because ballroom owners wanted bands that played sweet, danceable music, not black-oriented blues.

At the Trianon Ballroom in Chicago, the band got its notice after the first night--even though it had drawn a large crowd--on the grounds that it was “too loud and too fast.”

Then, in 1939, the band recorded “Woodchoppers Ball,” an instant hit that eventually sold a million records. The band was suddenly in demand and began to play such rooms as the famed Frank Dailey’s Meadowbrook.

At the Hollywood Palladium, Herman drew an opening night crowd of 4,800.

During the early ‘40s, Herman became sole owner of the band and acquired some of the superb young musicians that kept the quality of his music high: Chubby Jackson, Ralph Burns, brothers Pete and Conte Candoli, Neal Hefti, Flip Phillips, Bill Harris, Dave Tough. . . .

Man Behind the Sound

Burns was his piano player as well as a composer-arranger credited by Herman with being “as much responsible for our sound as anyone at that time.”

Igor Stravinsky was so impressed with the band that he wrote “Ebony Concerto” and conducted the Herman orchestra in the work at Carnegie Hall.

With most of the big bands giving up the financial struggle, Herman disbanded the “First Herd” in December, 1946, but reorganized after only a few months.

The “Second Herd” featured such top sidemen as saxophonists Stan Getz and Zoot Sims. It recorded “Four Brothers,” a Herman classic written by band member Jimmy Giuffre.

Be-Bop Period

With many of his young musicians well into the Dizzy Gillespie style, Herman’s band went through a period of performing be-bop. By the time he gave up that band in late 1949, Herman had lost $175,000.

Even after it went out of existence, however, it was named the Best Band of 1949 by readers of the jazz magazine Down Beat.

After working for a while with a sextet, Herman formed his “Third Herd” in the early 1950s.

With more top sidemen playing for him--including Nat Pierce, Carl Fontana and Urbie Green--Herman successfully toured Europe and stayed at the top of his field.

He constantly rejuvenated his band with infusions of highly trained young musicians from such sources as the Eastman School of Music, and he encouraged them to express themselves freely with their instruments.

String of Hits

Over the years, he recorded such top-selling numbers as “Apple Honey,,” “Northwest Passage,” “Early Autumn,” “Wild Root” and “Caldonia.”

He kept his bands abreast of changing styles while managing to keep them rooted in the Swinging Years.

He told an interviewer that his young sidemen of the 1970s and ‘80s had to be much better trained at the outset because “the music we’re playing these days is far more complex than it was 40 years ago.”

Herman was remarkable in being able to maintain a stable family life despite the almost constant time on the road. Charlotte, whom he married in 1936, traveled with him more and more during the later years.

Twice a Grandfather

In addition to their daughter, Ingrid, they have two grandchildren.

His indebtedness to the Internal Revenue Service was a large burden that kept him on the road and working in an effort to keep up the interest payments.

But by 1981, he and and his wife were able to spend much of their time in New Orleans, where the band established a base in a hotel nightclub named after Herman.

The bandleader had special ties to New Orleans from his early days--and the fact that in 1979 the band was chosen to represent the Zulu Society in the Mardi Gras parade. It was the first time a white man had been picked King of the Zulus.

Relief From the Road

Settling down in New Orleans offered relief from life on the road for Herman, who was seriously injured in the late 1970s when he fell asleep at the wheel driving from one one-night stand to another.

When the New Orleans deal was coming about, Herman told jazz critic Leonard Feather, “At this point in my life, with all the crap I’ve been through, I can’t think of a nicer way to go. So 1981, from where I’m sitting, looks a hell of a lot better than many, many other years I’ve known.”

Late in 1982, however, the New Orleans club folded.

A week later, the bandleader’s wife of 46 years died in Los Angeles.

His friends persuaded him to go back to work as the best therapy. He did so, reorganizing his band and going on tour in Europe.

In early 1984, after being a bandleader for almost 50 years, he told Feather, “I’ve come to the conclusion, as Duke Ellington did much earlier, that leading a band is really a hobby--something you do because you love it. As a business, it’s a complete flop.”

Funeral services are pending.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.