A New Age Dawns for Hiroshima

Hiroshima is one of a kind.

Try to think of another group of Japanese-American musicians that plays primarily instrumental jazz laced with pop, funk and assorted Eastern sounds. Or how about naming a band--Asian or otherwise--that features a woman playing the koto, an ancient Japanese stringed instrument?

This unique Los Angeles-based group has been around since the late ‘70s, but its appeal has been mostly limited to the jazz audience--until now. Hiroshima’s current album, “Go,” may propel Hiroshima into the mainstream.

The album, which recently spent more than two months on top of the Billboard magazine jazz album chart, has already sold more than 250,000 copies and shows signs of eventually cracking the 500,000-mark. One reason: the group’s often mellow, relaxing sounds has caught the ear of the yuppie-spawned New Age contingent.

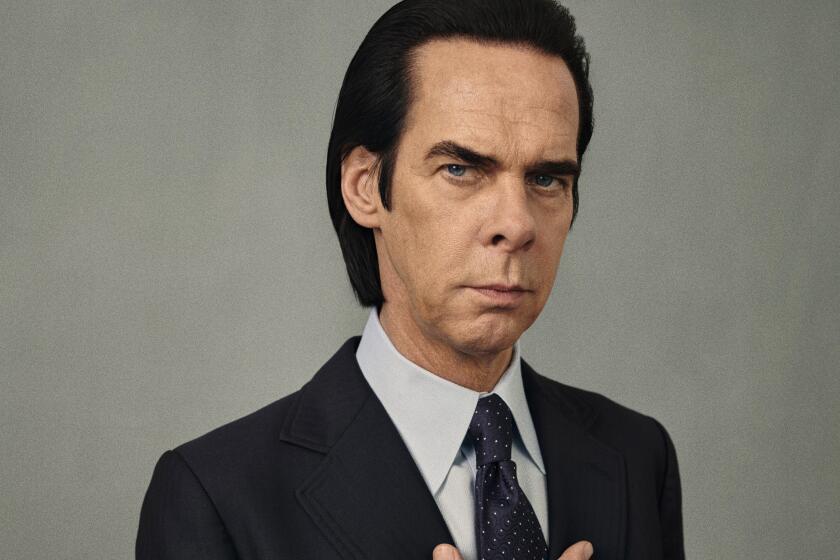

Leader Dan Kuramoto, a brash hipster not given to understatement, gloated about the group’s growing popularity, “Yeah, we’re bad . No need in trying to hide it.”

Kuramoto, 40, a self-taught musician who’s the band’s principal composer in addition to playing saxophones, flutes, keyboards and synthesizers, has two sides.

On one hand, he’s intelligent, erudite and serious. On the other he’s cocky, canny and street-smart, someone who’d be at home on any ghetto street-corner. He kept switching personas during an afternoon interview where the topics ranged from Eastern philosophy to the Lakers.

But he was mostly serious, particularly when discussing Hiroshima’s recent emergence. He made it it clear that he wasn’t pleased with the thought that the band’s new success was due to the connection with New Age, the homogenized, Yuppified soft jazz music that he described as glorified Musak.

“I’m not comfortable with us in this category,” he said. “Some of the music is OK, but there’s a lot that’s negative about the music too.”

Some of Hiroshima’s music does have the languid, creamy textures that characterize New Age music and have inspired its “elevator music” tag. Somewhat rankled, Kuramoto insisted: “Hiroshima does not play elevator music. We play complex, multicultural music. This is high-class stuff. It’s not throwaway music.”

Kuramoto was very careful about what he said. He’s too shrewd to offend the New Age crowd, which buys a lot of albums these days. “The New Age appeal has increased our white audience,” he admitted. “We want to appeal to whoever we can. We don’t want to be a cult band forever.”

Some critics have charged that Hiroshima has intentionally softened and whitewashed its music to fit the New Age category. They recall the band’s earlier music had a harder edge and stronger funk undercurrents.

“Don’t listen to that (junk),” Kuramoto snapped. “These people don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Most of the Hiroshima members--Kuramoto; his ex-wife, koto player June Kuramoto; percussionist John Mori; and drummer Danny Yamamoto--all were raised in predominately black, lower-middle-class sections of Los Angeles. The exception is the newest member--singer Barbara Long--who’s from Sacramento.

“Growing up in black community tied us to jazz and R&B;,” Kuramoto explained, speaking easily once the topic was away from the New Age matter. “That’s the music we heard all the time. I came out of a strong jazz background. My brother was a jazz pianist. But we all grew up listening to people like Santana, Marvin Gaye and Smokey Robinson. I was into jazz players like John Coltrane. This is all reflected in our music.”

Since its origins in the late ‘70s, Hiroshima has thrived on the support of the black community. Even now, its audience, Kuramoto noted, is predominately black.

Hiroshima started out as a fusion group. “We were fusing everything,” Kuramoto recalled. “At first we were just experimenting. We were playing jazz and rock and R&B;, but we also wanted to integrate Japanese music into our sound--forming an East-West blend.”

But the end of the ‘70s, when Hiroshima began recording for Arista Records, was a bad time to be playing fusion. “It died about then,” Kuramoto suggested. “Fusion bands were out. We had to put our music through some changes just to survive.”

However, there were limits.

According to Kuramoto, there were suggestions from the record company that the band should concentrate on funk. “(They) told us that we should sound like Rick James,” Kuramoto said, laughing. “That would have been ridiculous for us. Any black band can play funk better than us.”

This conflict arose in 1981, while Hiroshima was recording its third Arista album. It was never finished. After what he described as a bitter, two-year battle to be released from its Arista contract, the band signed with Epic Records in 1983 and was encouraged to pursue a jazz sound.

Their albums--1983’s “Third Generation” and 1985’s “Another Place”--enlarged their following and cemented their position as a force in the jazz community. But Hiroshima was still viewed in the industry as a cult band.

However Hiroshima should be categorized musically, the group has been a trailblazer, achieving prominence in the jazz-pop market unequalled by any other Asian-American band.

About that pioneering role, Kuramoto, said: “It might be easier for other Asians following us. When we were starting there were no precedents.

“There wasn’t any network of Asians in the record business we could turn to. We were out there on our own. If we had been afraid to go where no other Asians had gone we wouldn’t be here now. We just went ahead and did it. But sometimes I did wish there was a network of Asians like the network of blacks.”

In absence of that Asian network, Hiroshima made good use of the next best thing. “Blacks in the business really helped us,” Kuramoto said. “ We’ve been treated like a black band. Because of the music we’re playing that’s where we fit. It didn’t matter that we were Asians. And we’ve been treated well. I’m glad that black network was there.”

Will there ever be an extensive Asian network in the music business?

Kuramoto paused, then replied: “I’d like to think so. I’d like to see more Asians in the business, as artists and administrators. But not too many Asian parents steer their kids into this business. Part of it has to be because they don’t see a lot of other Asians in it.

“For artists, (the music business) is too uncertain. The odds are really against you. It took a long time for us to start making money--and we’re certainly not rich. My father was always telling me to get a real job. But I didn’t listen. Let’s face it. There are saner ways to make a living.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.