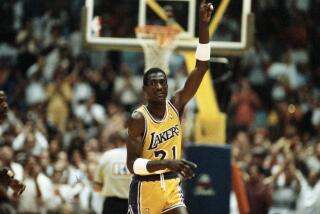

SHORT ROAD TO STARDOM : But Scott Has Hit Some Rough Spots Along the Way

For the kids shooting baskets on the playground of the Kelso Elementary School in Inglewood, it’s easier to dream with eyes wide open than closed. Every time they look across Prairie Avenue, at Jerry Buss’ Fabulous Forum, they are reminded of the possibilities.

That will be especially true on a night like tonight, when the limousines unload their celebrities under the awning of the Forum Club, and the TV trucks are stacked alongside one another, and thousands of people are streaming up the concrete entrance ramps to see the Lakers open defense of their National Basketball Assn. title against the San Antonio Spurs.

Long before Byron Scott was a Laker, he played on the Kelso court. Most of the time, he was over at Monroe Junior High or Woodworth Elementary or Darby Park, but the basket rims were slightly lower at Kelso, which made it the place to go for aspiring slam-dunkers.

Byron Scott remembers the first time he was able to dunk a basketball. He was in ninth grade, at 5-feet 11-inches already a little tall for his age, when one of the Morningside High varsity players asked the freshman if he could dunk.

Scott had tried about three or four times before, and had just missed.

The varsity player waited, watching as Scott, gathering speed, approached the free throw line.

“I extended out on the wing but as I went up, my mind kind of went blank,” Scott said. “When I jumped, I went blank. Then I sort of woke up.”

When Scott’s sneakers touched down, the varsity player spoke up.

“You dunked it kind of easy,” he said.

Scott, recalling that moment while sitting in the luxury of the Santa Barbara Biltmore, where the Lakers retreated for three days of preparing for the Spurs, laughed at the memory.

“After that,” Scott said, “I wanted to dunk every time.”

For Scott, who grew up in Inglewood and still lives nearby, the route from the playground to the Forum would, on the surface, seem as simple as crossing the street.

But if it were that easy, Scott’s brother Jeff wouldn’t be doing time in a Utah prison.

If it were that easy, there would not be a picture in Scott’s mother’s house of Little G, one of the younger kids in the neighborhood in whom Scott had taken an interest, who was stabbed to death in a gang fight.

More than once, Scott said, he had tried to keep Little G out of fights.

“What are you doing here, Little G?” he would say.

“They did this to me, B,” the would-be warrior would respond, before letting Scott walk him away. But Scott couldn’t be there every time.

If it were that easy, Scott would not have to think about another friend, who lived just three blocks away, coming to him one night asking for money. Scott, seeing that the friend was high on crack, turned him down. A couple of days later, the friend was shot and killed. He had owed someone--probably a dope dealer--some money.

Nothing, Scott knows only too well, is ever that easy.

It was a Thursday night last June, the Boston Celtics had just whipped the Lakers to send the championship series back to Los Angeles, and Magic Johnson couldn’t recall ever seeing Byron Scott as low as he was at that moment. They spent almost the entire night talking in a Boston hotel room--Michael Cooper was there, too--trying to relieve Scott of the depression that seemingly had gripped him the moment he had stepped onto the Boston Garden floor.

Scott had played brilliantly in the first two games of the series at the Forum, scoring 20 points in the first, 24 in the second, and making 18 of 26 shots.

But in Boston, he had all but disappeared into one of the canyon-sized cracks in the Garden’s parquet floor. In Game 3, he scored 4 points, on 2-of-9 shooting. In Game 4 it was 8 points, 3-of-10 shooting. Game 5 yielded just 7 points, 3-of-10 shooting. And all the old doubts and taunts echoed from the Garden balconies: Byron Scott choked in the big games, Byron Scott played scared in Boston, Byron Scott was a Hollywood fraud.

On that night, Scott had begun to believe that maybe it was all true.

“The Boston mystique, the crowds, what they were writing in the papers, I let myself get to the point where I thought maybe I couldn’t get the job done,” Scott said. “I was thinking about my shots, and how I wasn’t taking them.

“That stuff pretty much took over me. I pretty much was listening to what everybody was saying.”

What hurt most, Scott said, was that he feared there might be doubt in his teammates’ eyes.

“I thought maybe they had lost confidence in me,” Scott said. “That hurt more than anything, that my two best friends on the team--Magic and Coop--might have lost a little confidence in me.”

Johnson and Cooper spent hours trying to convince Scott otherwise.

“We had to make him understand we weren’t down on him,” Johnson said. “We reminded him that we were still ahead in the series, not to worry about what other people were saying.

“We needed him to come in and help us by playing hard in other areas--even if he wasn’t scoring. We needed him to do a good job on defense.

“The Lakers don’t get on each other. They never have since I’ve been here. And we told him we needed him.”

His friends were concerned enough, however, to ask Coach Pat Riley to talk to Scott before the next game. Riley called him into his office for a meeting that didn’t last more than five minutes, but in which he tried to convey an important message.

“Players have a tendency to transfer everything on themselves, and that everyone is blaming them,” Riley said. “I told him that we were supporting him, but we needed him to perform. I was very straightforward with him.

“I used Kareem (Abdul-Jabbar), James (Worthy) and Buck (Magic) as examples. If you want to walk in their shoes, you have to learn to take the criticism and perform.”

When Scott entered his office, Riley wrote in his book, the player had stared like a face carved inside an Egyptian tomb. By the end of the meeting, though, Riley’s point seemingly had hit home.

By the end of the next afternoon, the Lakers were champions, and although Scott had had another quiet game--he made 4 of 7 shots for 8 points--the Celtic vise had begun to slip.

Last December, on the Lakers’ first visit back to Boston since the playoffs, Scott finally got unshackled from his past. In a thrilling 1-point win over the Celtics, won on an improbable bank shot by Johnson, Scott scored 21 points on 8-of-15 shooting. And just in case the message hadn’t registered, when the Celtics came to the Forum in February, Scott scored a career-high 38 points in a runaway Laker win.

“I still don’t think I’ll visit there as far as taking a vacation,” Scott said of Boston. “But after we won the championship, I thought about going back there as soon as possible to redeem myself. As soon as the schedule came out, I looked forward to that game.”

And at practice the day before that game, Magic said just the right things, Scott said.

“He told me, ‘B, DJ (Dennis Johnson) is too slow, and Danny (Ainge) can’t guard you,’ ” Scott said. “That day, when he said it, I thought, ‘If he feels that way, I know I can score on these guys.’ All I wanted to do was come out and play my game the way I know I can play.”

And what Boston might have found out first, the rest of the league learned shortly thereafter: Scott’s game had ascended to a new plane. Two games after the win in Boston, Scott scored 31 points against the Phoenix Suns. In his first four seasons with the Lakers, Scott had scored 30 or more points nine times. This season, he broke the 30 mark 11 times.

Thirty times this season, he led the Lakers in scoring, and wound up as the team’s leading scorer for the season, with a career-high average of 21.7 points a game, an increase of nearly 5 points a game from a season ago.

He shot a career-high 52.6%, compared to 48.9% last season, averaged 37.6 minutes a game, which put him among the league’s iron men, and had personal highs in rebounds, assists, steals and free throws attempted and made. He also took on the opposition’s top gun defensively and more than held his own.

More important than the numbers was this: When it came down to winning time, Scott, who so often in the past had deferred to Johnson or Worthy or Abdul-Jabbar, was the man frequently called upon to deliver. That means Riley now has one more trump card to throw in the playoffs.

“I thought last year was a breakthrough season for Byron,” Riley said. “I didn’t realize how much higher he could go. He won at least 10 games outright for us this season, and he was strong every single night.”

Riley credits Johnson for being a source of inspiration for Scott, who readily concurs.

“I’ve called more plays for Byron this year than ever before,” Riley said. “Before, we almost never called a play for him when it counted.”

In the past, Scott said, he had taken steps each season to improve his game. “This year wasn’t a step,” he said. “It was a leap.

“Now I know that whoever’s guarding me is in for a rough night, that they’d better be ready to give me 48 minutes of strong aggressive defense. Because I’m going to give them 48 minutes of strong, aggressive offense and defense. They’re going to have their work cut out for them.”

Scott, once known for his jump shots and little else, has opened defenses by taking the ball to the basket.

“A couple of years ago, my shooting over 300 free throws would have been unheard of,” Scott said. “Now, I have people backing off on me, giving me the jumper, which is still the strongest part of my game.”

At 27, Scott says, he has only begun to scratch the surface of his playing ability. To be sure, he has only begun to tap his potential earning power. Scott, who signed a 1-year contract for $600,000 last season, figures to be in line for a substantial raise.

Maybe then, he said, he’ll move out of the neighborhood--but only if he can move his family, including his parents, with him.

For now, however, Byron Scott remains a homeboy.

“You could leave the neighborhood for 10 years and come back, and you’d still be a homeboy,” Scott said.

Scott has gone to see the controversial gang movie, “Colors,” twice. The first time, he went with Cooper and Johnson. The second time, he took his wife, Anita.

“She didn’t like it because of all the killing.” Scott said. “But to me, it was real.”

No, Scott said with a smile, he never wore gang colors, though the Crips and the Families were in abundance in his neighborhood. When he was growing up, he said, the gangs left athletes alone.

“They admired athletes,” he said. “You never heard about an athlete getting shot over just nothing. There was never pressure put on me to join a gang, although if I went up to the leaders of the gangs--and I knew them all in the neighborhood--they definitely would have invited me to join.

“The athletes had their own sort of gang. We’d walk down the street, and a carful of gang-bangers in a station wagon would pull up, and they’d say, ‘What’s up, blood?’

“And as arrogant and as tough as we thought we were, we’d answer back, ‘What’s happening, cuz?’ And they’d turn their car around and chase us.”

That was a world that his wife, Anita, the daughter of a career serviceman who lived abroad for many years, found to be very foreign.

“I remember taking her into Inglewood, and she started locking all the doors,” Scott said. “I said, ‘What are you doing that for? This is my neighborhood.’

“In Inglewood, I can go anywhere I want without it being a hassle. Everybody there knows me, and respects me.”

More than once on his way home from practice, Scott said, he has stopped to break up a potential gang fight. He acknowledges that the gang problem is worse now than when he was growing up.

“They see the dope dealers with their fancy cars and clothes, and see there’s a way to make fast money, tax-free,” Scott said. “To them, maybe it’s a way out of the ghetto.”

And maybe the odds of getting out of the ghetto the way he went--with a basketball--are nearly as prohibitive.

“No doubt you may have better odds as a dope dealer,” Scott said. “But the odds are much worse of staying alive till you’re 25 or 26.”

There is the picture of Little G to remind him of that.

Then there is his brother Jeff who, unlike Scott and his sisters, Candice and April, couldn’t stay out of trouble. He had a drug habit, said Scott.

“My brother was heavy into drugs and at one point, I turned my back on him,” Scott said. “My feeling was, ‘He chose that life, and I don’t want any part of it.’ ”

Scott said his brother went overseas for a while after leaving home, then wound up in Utah, where he is serving time on a burglary rap.

“He’s called me from there a couple of times,” Scott said. “He says he’s clean now, and he’s also told me the truth about the crimes he’s done.

“Sometimes I blame it on myself. The pressure of me being a great athlete, getting the praise of my mom and pop, maybe there was a lack of attention there. Maybe this was his way of getting attention.”

There is more than one game played out on the playground.

Scott envisions a different game for his own children--son Thomas and daughter Londen Brenae.

Asked what he hoped to accomplish in his life, he said: “No. 1, I want to stay married to my wife for the rest of my life, and watch my kids go to college and get a good education.

“And I want to be able to get the things in this world that I want, that when I’m finished with basketball, I won’t have to be worried about getting a job. I also want to play for 10 or 11 years without a major injury.

“But that’s basically it. I’m a very basic person.”

Basic enough to remember the hours spent at Kelso and Monroe and Woodworth, and his link to the kids behind the chain-link fences. One homeboy’s dream begets another.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.