Cartoon Writers Hope to Ink Union Contract

It sounds like someone’s idea of a sequel to this year’s Hollywood writers’ strike. Frustrated with what they believe are inadequate payments, lack of benefits at some studios and insufficient rules governing credits, writers of television cartoon shows have formed a new union.

The fledging group, the Animation Writers of America or AWA, claims more than 110 members, roughly half the active cartoon writers in Hollywood. As its first goal, the 3-month-old union is trying to organize writers at DIC Enterprises in Burbank, a non-union, 6-year-old company that has emerged as the industry’s busiest cartoon factory with such shows as “The Real Ghostbusters” and “ALF.”

It won’t be easy. DIC (which rhymes with squeak) has successfully fought two other organizing efforts in the past four years and opposes this drive as well. DIC lawyer Greg Payne argues that its writers, nearly all of whom are free-lancers, are independent contractors who should not bargain collectively.

But the union has given the National Labor Relations Board cards signed by 60 writers requesting an election so writers can vote on whether the group should represent them. NLRB officials are now considering the union’s request to schedule an election.

Cartoon writers can make anywhere from a few thousand dollars a year to well over $100,000 for an elite few. A script for a typical half-hour cartoon episode--usually 22 minutes after allowing for eight minutes of commercials--runs about 40 to 60 pages, for which studios typically pay from $3,000 to $6,000.

By contrast, members of the Writers Guild of America who write a half-hour network television show get paid a minimum of $12,176, plus residuals when the shows are rebroadcast.

The cartoon writers’ move to form a union stems from two major frustrations. Unlike live-action television writers, who are guild members, cartoon writers do not enjoy such benefits as tough rules spelling out how work is to be credited, strict guidelines on payments for writing scripts on speculation and, most of all, residual payments when cartoons they write are rebroadcast.

“We are the Cinderellas of the industry. We are the stepchildren,” said Sheryl M. Scarborough, the union’s president, who recently worked as a story editor on Marvel’s new television show, Dino-Riders.

The second major frustration they describe is with the venerable Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists Union Local 839 in North Hollywood, which represents a broad group of animation workers at the major union animation houses including Walt Disney, Hanna-Barbara, Ruby-Spears, Marvel and Filmation. Besides representing writers, their members do such work as coloring frames and drawing story boards. The 1,000-member local has been pummeled in the past five years, losing more than half its membership as animation studios shifted labor-intensive production work to studios in the Far East, where costs are substantially cheaper.

Cartoon writers argue that the Cartoonists Union Local 839, besides being weak, has primarily represented production workers in the past, paying little attention to writers’ needs. Writers add that one of their biggest gripes is that the union has always called them “story persons” instead of writers.

“We feel we have as much in common with other people in Local 839 as if we were in the pipe fitters union,” said Mark Evanier, a writer who works on the Garfield & Friends show on CBS.

Studio executives and other union officials give the new cartoon union little chance of succeeding if the industry’s financial woes continue. Studios, they note, are under intense pressure to limit costs because of a glut of cartoon shows on the market, competition from cable channels such as Disney Channel and Nickelodeon, lower spending by cartoon sponsors such as toy companies and an overall slump in the syndicated, or off-network, television market.

Union Weak

Harry (Bud) Hester, business agent for the Cartoonists Union Local 839, acknowledges that his union is weak, but adds that the cartoon writers would have the same problems he has bargaining with the studios.

“I think they are in a little bit of a dream world because they feel if they can get a contract, they’ll get a Writers Guild contract,” Hester said.

Hester points to the union’s stalled negotiations with the major animation studios as an example of how difficult negotiating has become. The union’s contract expired July 31. Hester said the union would be happy signing a contract that maintains the status quo, but studios want a more flexible contract loosening up such things as rules governing weekend work.

“We are just trying to survive by seeing how little we can give up,” Hester said.

The new cartoon writers’ union is prevented for now from representing writers at Cartoonist Union studios. But some AWA members say they would ultimately like to bargain for all television cartoon writers, including those at studios now negotiating with the Cartoonists Union.

Began in 1986

The new union got its start two years ago when about 50 cartoon writers began sending electronic messages to one another from computer terminals and they formed something of social organization last year. In July, the group filed papers with the NLRB to become a union, holding meetings in a Burbank real estate office.

But for all the union’s enthusiasm, its leaders are reluctant to talk about what some of its members say is the rank and file’s ultimate goal: having the Writers Guild represent them. Cartoon writers believe the guild has much more clout and has shown interest in representing cartoon writers.

“There is nobody who writes animation who does not want to be in the Writers Guild,” cartoon writer Evanier said. Indeed, some cartoon writers already are members of the Writers Guild, but the guild can only represent them in issues related to their live-action work.

Twice since the early 1970s, cartoon writers have sought to break free from the Cartoonists Union, most recently in 1982 when the Writers Guild sought to represent them. Both times, the cartoon writers failed to meet certain NLRB requirements to leave the union.

Labor Tensions

This has been a year of labor strife in Hollywood. First came the bitter 5-month Writers Guild strike against producers that shut down production, causing delays in launching the networks’ fall television season. Now, truck drivers who are members of the Teamsters are on strike against producers.

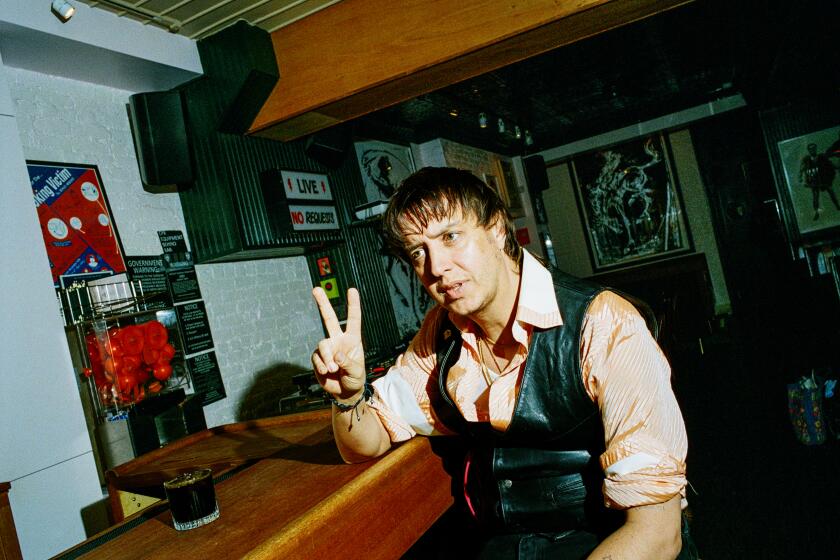

The new union selected DIC as its first organizing target because it is the only major animation studio that is non-union, it is highly visible and is the busiest. The studio is led by former Hanna-Barbara writer Andy Heyward, who since late 1986 has been burdened by about $70 million in debt taken on when he led a buyout of the studio along with Prudential Insurance and Bear, Stearns.

Local 839 failed in efforts to organize workers at DIC in 1984 and last month.

Unusual Approach

Heyward has a reputation for going to extraordinary lengths to cut his costs to get cartoons on the air. He often does work for hire while giving up domestic ownership rights to the cartoons, something few other studios do, and aggressively underbids his rivals. He also has used exotic financing methods such as taking advantage of Canadian tax shelters by having a large amount of production work done there.

Writers complain that DIC does not offer its free-lance writers such things as health insurance benefits and has historically paid at the low end of what studios pay. And some cartoon writers disparagingly say DIC stands for “Do It Cheap.”

Payne, DIC’s lawyer, argues that because the company considers writers independent contractors, it doesn’t believe they are entitled to the same benefits full-time employees receive. And he denied DIC is stingy in paying writers, contending it is competitive with what other studios pay.

Rules on Credits

The AWA officers are reluctant to talk strategy about what they would ask from DIC or any other studio whose workers they might ultimately represent. Initially, they say, they would like to get tougher rules credits to reduce such things as “gang credits,” in which all writers who work on a series are listed in a group at the end of a show instead of giving credit to the writer who wrote a specific episode. Another sore point is the practice of speculative writing that pays little or nothing when a script is rejected.

The stickiest issue in the future for the AWA will be trying to win residual payments. Hester, of Cartoonist Union Local 839, believes the writers won’t get them.

Still others point to the Writers Guild strike as an example of how hard studios are willing to fight over residual-related issues. J. Michael Straczynski is a story editor and writer who has worked on such shows as “The Real Ghostbusters” and the new live-action “Twilight Zone.”

He said: “The WGA strike was a sobering note for the AWA because it demonstrated before our eyes that achievement in union negotiations depends on great pain and sacrifice. It’s not going to be easy, and it’s going to hurt.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.