STAGE REVIEW : Triviality Prevails in ‘Stieglitz’

SAN DIEGO — Maybe playwright Lanie Robertson is right about Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe. Maybe they made their 22-year marriage work by making a game of it. Alfred would play the jolly professor, and Georgia would play the impatient little girl.

If so, it’s no wonder they needed to take long vacations from one another. “Alfred Stieglitz Loves O’Keeffe” at the Old Globe Theatre’s Cassius Carter Center Stage reduces two distinguished American artists to TV characters--almost to sitcom characters. Honestly, Alfred! Now listen here, O’Keeffe!

We open on the day of Steiglitz’s death in 1946. Georgia (Melora Marshall) has just delivered her husband’s remains to a funeral parlor. She gets back to the apartment--and there’s Alfred (Paul Sparer).

But, but, but, you’re dead, says Georgia.

Nonsense, says Alfred. I live here, remember? And soon he’s wagging his finger at her just as he did in the good old days when he owned an art gallery in New York and she was just a kid from Wisconsin. Ah, the good old days.

And we are back to the past. This is not a very original way to open a biographical play, and for the first half of the evening, biography is all we get. Stieglitz and O’Keeffe spend far too much time informing each other, for our benefit, of things that they already know. “Now why am I telling you all this?” says Stieglitz at one point. Excellent question.

At intermission, we’re wondering why Robertson is telling us all this. In the second act, however, the play assumes some forward motion. O’Keeffe has a nervous breakdown and delivers a fine, frank speech about her gratitude to Stieglitz for having brought out the artist in her--and her resentment that, as a woman, she needed to have a man bring her out.

Here actress Marshall finally gets to play O’Keeffe as a serious and complicated person, and we see the play that might have been.

Act II even develops a bit of suspense. Will O’Keeffe ever recover from that dreadful review by her husband’s friend, Marsden Hartley--the one where he suggests that her flower paintings are actually about sex?

One wonders whether O’Keeffe was really this disturbed by the suggestion, as opposed to being exasperated by it. Certainly in her later years O’Keeffe didn’t give a damn what people saw in her paintings. But the theme does help to knit the story together and provides an ending of sorts.

On balance, though, the play tries so hard to make Stieglitz and O’Keeffe human that it trivializes them. Rather than presenting them as two tough-minded artists who had hammered out a reasonable way of living together, we see them as two charming eccentrics who “can’t live with each other and can’t live without each other.” There’s no flint here, and it puts the actors at a disadvantage.

Sparer’s solution is to squeeze as much fun as he can from the stereotype of the twinkly-eyed professor who knows how to get around his eternal child bride. Sometimes his Stieglitz even seems a self-spoof. This would be interesting if we could see the iron underneath, but that’s not in the game plan.

Marshall goes for spontaneity, stressing the idea that O’Keeffe is a woman in touch with her feelings. Most of them are feelings of frustration--with Alfred, with the critics, with the secondary position of women. What is missing (except now and then in her face, in silent moments) is the granite determination that we associate with the real O’Keeffe.

One sees the acting problem. Were Sparer and Marshall to give tougher performances, it wouldn’t be the play. You can’t fault them--or director Robert Berlinger--for staying within its margins. You can only regret that the margins weren’t set as wide as the lives under discussion.

The physical production does remind us that these were both intensely visual people. Light was food for Stieglitz the photographer and O’Keeffe the painter. Lighting designer Peter Maradudin will lay on an ochre wash to evoke O’Keeffe’s desert, or burn in a strong white keylight to suggest a Stieglitz portrait.

Hugh Landwehr’s in-the-round setting also pays tribute to each artist, and costumer Christina Haatainen remembers that O’Keeffe favored dramatic black-and-white outfits, while Stieglitz didn’t care how baggy his trousers got.

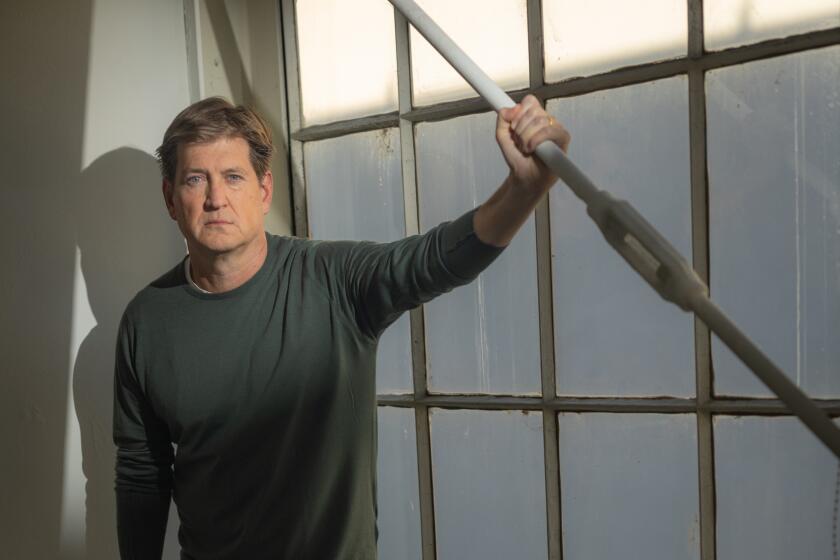

But when her dead husband tiptoes out of O’Keeffe’s life, reassured that she will keep on painting without him (as if she hadn’t spent the last 15 summers painting alone in New Mexico), the spectator isn’t sorry to tiptoe away either. On the way out, he salutes the portrait of Stieglitz and O’Keeffe in the theater lobby. Who needs a mediocre play about remarkable people?

Plays Tuesdays-Saturdays at 8 p.m. and Sundays at 7 p.m., with Saturday-Sunday matinees at 2 p.m. Closes Feb. 19. Tickets $14-$25. Balboa Park, San Diego; (619) 239-2255.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.