Casting Across the Color Line : Nontraditional Choices Grow, as Theaters Examine Roles

Three years ago, a handful of Old Globe Theatre patrons heard that Earle Hyman, the black actor who plays Bill Cosby’s father on “The Bill Cosby Show,” had been cast as the lead in “Julius Caesar.”

They demanded their money back.

Two years ago, when the La Jolla Playhouse production of “The Tempest” used a black actor as Ferdinand, the love interest of the white actress who played Miranda, letters of protest were mailed to artistic director Des McAnuff.

Nontraditional casting--the placing of minorities, women and the disabled in roles associated with white, able-bodied male actors--is not a new concept. But it’s never been a hotter issue.

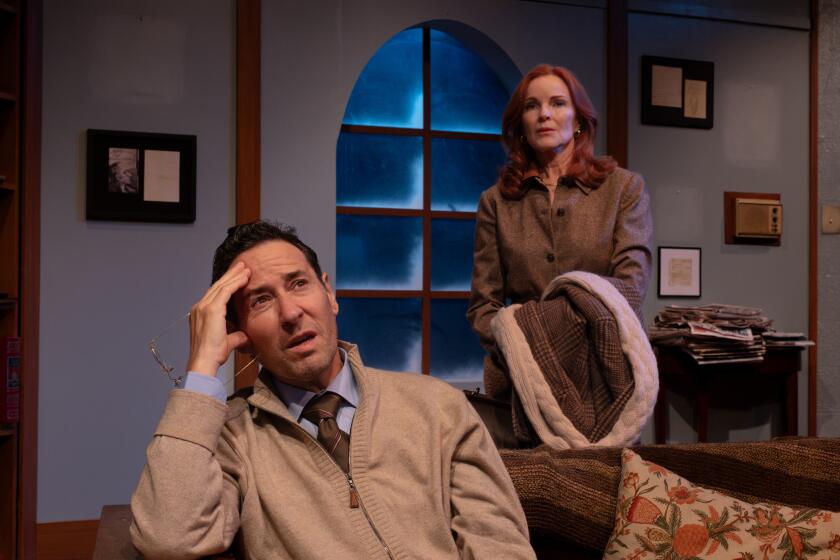

Does it make sense to have blacks and Latinos play generals and nobles as they did in “Coriolanus” and “Timon of Athens” at the Old Globe last season? Does it make sense for a deaf, non-speaking actor to ply Caliban in “The Tempest,” as Howie Seago did at the La Jolla Playhouse two years ago? Does it make sense to cast a woman instead of the male psychologist called for in Teatro Meta’s “La Fiaca” at the Marquis Public Theatre?

New York magazine’s John Simon is one powerful critic who doesn’t think

so. As the keynote speaker for the Assn. for Theater in Higher Education meeting in San Diego last year, he blamed nontraditional casting for the deteriorating quality of American theater, saying that, if it keeps up, “We’ll soon have wheelchair actors playing Romeo.”

Since there are wheelchair-bound actors willing and able to do it, the prospect is not as outrageous as Simon thinks. The stage has always been filled from the available talent pool--Shakespeare himself cast young men as women because it wasn’t comely for ladies to perform--and today’s regional talent pools reflect the heterogeneity of their communities.

Despite the demands for refunds by some ticket buyers, San Diego audiences seem ready to accept nontraditional casting.

A black actor played the key role of Tullus Aufidius in the Old Globe’s production of “Coriolanus” last fall, and the show was one of the biggest hits of the season. The racially mixed group of sycophantic nobles in the Globe’s “Timon of Athens” elicited little comment. There were no protests when the San Diego Rep cast a black actor in “Glengarry Glen Ross,” or a black actress in “Six Women With Brain Death, or Expiring Minds Want to Know,” two shows that had previously been done with all-white casts.

For theater producers, there are economic as well as artistic reasons for pursuing nontraditional casting. Showing a record of cross-cultural casting often is a prerequisite for national, state and private funding of the arts. The newly articulated policy of the League of Regional Theatres (LORT) is to “encourage its members to actively solicit the participation of ethnic minorities in the casting process.”

To this end, LORT asks its member theaters to turn in an annual casting and auditioning survey in which they report the numbers of women and minorities cast in nontraditional roles, which LORT, in turn, discloses in joint committee meetings with Actors Equity. The policy may be just a step away from Chicago’s affirmative action program, in which contracts approved by the local branch of Actors Equity penalize theaters for failing to maintain hiring quotas.

The future promises even more of an incentive. Harry Newman, executive director of New York’s 3-year-old Nontraditional Casting Project, said that, if his organization succeeds in raising $1 million, he intends to use that as reward money for theaters that hire black actors, designers, directors and administrators.

Other evidence is beginning to scare theaters. A four-year Actors Equity study completed in 1986 shows that 90% of the productions surveyed were made up of predominantly white, male casts. Couple that with census figures projecting the population of states such as California as less than 50% white by the year 2000, and it’s easy to picture an incredibly shrinking audience. Just as black baseball fans failed to turn out for major league baseball until well after Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947, directors fear that, if theater keeps on its current course, they could compromise their own future.

That’s a forecast nobody likes.

The figures come as no surprise to Raul Moncada, artistic director of the Old Globe’s Teatro Meta. As an actor, Moncada worked under the name Jeffrey Grimes for years before returning to his original Cuban name.

“In Hollywood, my name got in the way of acting jobs, but I didn’t feel like changing it again,” Moncada said. “So, I went into stage-managing. Now, I’m in the position to do something about all the injustices I went through. But you have to be extremely, extremely careful.

“The flip side of this thing was that, when a theater company in Chicago hired a white Dorothy for ‘The Wiz’ (a traditionally all-black musical), it went into arbitration with Actors Equity. I would love to see all this come to an end and see everybody hire everybody.”

But an end is nowhere in sight. Observers of local theater say solutions seem no more black and white than the casts on San Diego stages. Do theaters need changes at the acting level, the administrative level, or both? Should Actors Equity mandate affirmative action in the spirit of civil rights legislation, or should directors maintain the artistic freedom to cast as they see fit? Are black and Latino theater companies needed, as black director and UC San Diego Prof. Floyd Gaffney insists? Or, is it the responsibility of mainstream theaters to lead the way, because only they can reach the widest possible audience?

If theaters do make changes, will they risk antagonizing the white, middle-class audience they already have? Some say movies and television shows still make distinctions between white and black shows for a reason, with most mixed shows having whites in the romantic leads and blacks in supporting roles.

Lena Horne has said that the reason her one-time roommate, white actress Ava Gardner, got the part of Julie--the girl of mixed color who marries a white man in “Showboat”--was that a movie depicting a white man kissing a black woman just wouldn’t make it in the South. And, with the exception of a handful of such interracial message films as “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” and “One Potato, Two Potato,” not much has changed in Hollywood.

Symposiums, largely sponsored by the Nontraditional Casting Project, have succeeded in making the concept a buzzword in the theater world. But few havens for nontraditional casting have as yet materialized.

The reputation of Joseph Papp, artistic director of the New York Shakespeare Festival, who pioneered nontraditional casting in the 1950s, leads some people to see New York as the Mecca of the movement. But one look at commercial Broadway tells a much different story.

Only last year did Radio City Music Hall hire a black Rockette, and then, as a result of a lawsuit. Producer David Merrick kept his long-running “42nd Street” chorus line all white until its closing day this week. Newman, whose Nontraditional Casting Project monitors these changes, sees an uncomfortable subliminal message in the current all-white production of “Our Town” at Lincoln Center.

“If you have a production of ‘Our Town’ with an all-white cast whose logo is the Earth, that’s like saying the Earth belongs to white people,” Newman said.

Of course, even if the world did change overnight, Teatro Meta’s Moncada does not believe that would translate immediately into minority audiences.

“You need to build the audience,” he said. “They (minorities) don’t have the theater-going tradition. They don’t have the money. That is why the Globe is offering a Latino play festival at the Progressive Stage Company (starting Jan. 27) for $3 to $5 a ticket.”

Still, Moncada sees an interim benefit even for white audiences who may grow weary of seeing the same old shows done the same old way again and again.

“Rather than thinking of nontraditional casting as something that alienates the white, middle-class audience, you should see it as something to keep them,” he said.

That thought is echoed by Benny Sato Ambush, who earned his master of fine arts degree under Gaffney at UCSD and is now producing director of the Oakland Ensemble Theatre.

“How many times can you do ‘Hedda Gabler’?” Ambush asked. “Most professional resident theaters are run by white males, who have been virtually exclusive about perpetrating Euro-American culture. If you make changes, you may lose some of your traditional subscription base, but you will attract others who will be interested in the spiciness.

“What we’ve done on our stage is a variety. You will see mixed-cast shows by black authors. You will see mixed-cast shows by white authors. We’ve had whites who have said we don’t know our own mind and have a confused identity. We’ve had blacks who criticized us for selling out. Fine, let the debate rage. “It’s the dialectic of change, and it’s the mandate of this country. If all men are created equal, let me see it. Let us be the harbingers of the brave new world and claim our birthright as artists and say what’s possible, as opposed to what is and what has been.”

Nanci Hunter and Victor Smith of the San Diego Actors Co-Op believe that selling audiences on the advantages of nontraditional casting will encourage producers to take up the banner. Hunter and Smith are shooting a documentary for Cox Cable that will include a nontraditional casting symposium at the June 5 at San Diego Repertory Theatre.

Hunter, a blond, blue-eyed veteran of San Diego stages, has not experienced much prejudice because of her Mexican heritage, but Smith believes his choice of roles has been limited by being both black and Cuban.

In their video, called “Traditions for Tomorrow: the Actor, the Theater and You,” they plan to show how the four types of nontraditional casting outlined by Actors Equity work.

Two of the most widely used types are societal and cross-cultural casting. In cross-cultural casting, a play is transferred to a time or place that lends itself to minority casting. The setting of “Coriolanus” at the Old Globe suggested a conflict between the United States and Central America; the setting of the La Jolla Playhouse production of “The Tempest” suggested Third World conflict. In societal casting, parts that in real life might be lived by minorities, women or the physically disabled, may be cast accordingly. So, black Latino actor Damon Bryant played a man being bilked in “Glengarry Glen Ross” at the San Diego Repertory Theatre.

The more controversial choices are conceptual and color-blind casting. In conceptual casting, minorities are used to make a point, as when a black was cast as Judas among the white Jesus and apostles of Broadway’s “Jesus Christ Superstar,” a choice that offended many black directors and actors. No objections were made to “Blow Out the Sun,” the Sledgehammer Theatre adaptation of “Woyzeck” that cast whites as officers, and blacks and Latinos as foot soldiers and their girlfriends, as a way of underlining modern class conflict.

The San Diego Rep demonstrated color-blind casting when it cast Whoopi Goldberg as the wife with a white husband in the 1977 production of “A Christmas Carol” and again when it cast Bryant as a Mr. Fezziwig with a white wife in last year’s “A Christmas Carol.”

One of the risks of color-blind casting was pointed up in the recent San Diego Junior Theatre production of “Rumpelstiltskin,” in which the single black actor in the show played the villain. The part was cast color-blind, said Lizbeth Persons, marketing and public relations director for the theater.

One irate audience member complained that it gave the wrong impression.

“Unfortunately, we live in a community infamous for its white supremacists, be they Nazis or Skinheads,” Olivia Flores Jourdane wrote in a letter to The Times. “I will not charge the Junior Theatre with intentional racism. But the apparent lack of sensitivity in performing a good/evil fable with a white ‘good’ cast and the sole black playing the ‘evil’ Rumpelstiltskin was too offensive to remain silent.”

There is, of course, another controversial solution that Equity doesn’t talk about--the scheduling of plays by and about blacks, Latinos, Asians and females.

Those who support work like the “The Colored Museum,” “Burning Patience” and “Six Women with Brain Death” at the Rep, and “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone,” “Blood Wedding” and “Tea” at the Globe, point to the jobs such shows provide for minority actors, writers and directors and the eloquent exposure they give to black, Latino, Asian and female perspectives.

Those who object fear that such work encourages a cultural apartheid that allows a theater to meet its quota of minorities while keeping them separate from all-white shows.

These apprehensions run so deep in the acting community that directors occasionally complain that they don’t even get enough minority actors auditioning for non-minority roles because the actors assume they aren’t wanted. In the vacuum, talented actors such as Carol and Bryant have been auditioning and getting cast-- nontraditionally --by directors who may not have been looking for minority actors. But, they found Bryant would do just fine in “Glengarry Glen Ross,” and Carol would be just right for “Six Women.”

“Maybe they thought they wanted to use one type of person, but, once they see me, then they’ll have a different idea,” Carol said, explaining why she turns out for all the general auditions she can. “When I was born, they said, ‘It’s a girl,’ not ‘It’s a black girl.’ ”

Such is the colorblind philosophy for which the theater world seems to be groping.

“We feel that art should lead the way to breaking down prejudices in terms of ethnic origins,” said Thomas Hall, managing director of the Old Globe Theatre and national president of LORT. “Clearly, there are certain instances where it is germane. If you are having someone who is playing a white racist, you don’t cast a black. But, in the case of ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ there would be nothing wrong with casting Romeo and Juliet as a mixed couple. Or casting Romeo in a wheelchair.”

“I think people are committed,” Moncada said. “But it’s a long road.

“We all want results right now because it’s so hot in the news. But it’s a process of evolution, not revolution. What keeps American theater going are the new people coming in, the new blood. These are the Italians of long ago, feeding into the theater a whole new way of looking at our society.

“We have to be very patient and not give up.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.