Return of the Prodigal : Twice Driven From Parliament, British Author Jeffrey Archer Is Back in the Chips and in Favour

- Share via

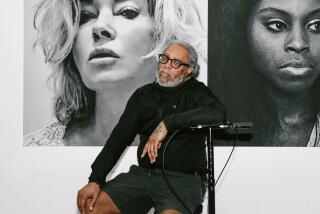

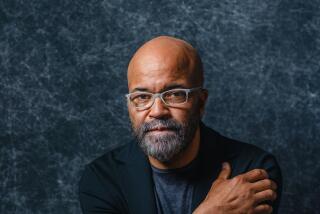

Jeffrey Archer is Britain’s best-selling author and its worst bet to become prime minister.

He’s also a twice-resigned, doubly shamed politician who toughed his way back from bankruptcy to earn enough from six novels and two miniseries to buy a London theater, a country estate near Cambridge and a 400-work art collection that includes Renoir, Pissarro, Picasso and Van Gogh.

He would give it all to be the first 48-year-old captain of England’s cricket team.

He may have to settle for being Britain’s next ambassador to the United States.

“Very flattering,” Archer said at the prospect of such an offer. He folded his napkin and tidied the debris of a recent mixed grill lunch at the Westin Bonaventure. “And what a wonderful job.” Not, he insisted, that the job has been offered.

Subject of Speculation

But hasn’t there been diplomatic speculation in London that Archer--an Atlantic commuter, an admirer of the United States and, most important, a long and loyal confidant of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher--would make an ideal ambassador to the court of George Bush?

“No comment,” he said. Have there been any discussions on the matter? “No.” But, Archer conceded, if asked he certainly would serve as ambassador.

And he and his wife, Mary, were indeed asked to Chequers Court, the prime minister’s official country residence, for a small dinner party (“of 20 guests only four were politicians”) the day after Christmas.

“The press thought that was very pointed,” Archer said. “We (Thatcher and Archer) talked about the next election.” Was there talk of an appointment for Archer? “She never does. That’s not her style.

“Her style is to make it clear you are in favor. And to (inform) everyone else who is watching that you are in favor.” So Jeffrey Archer has been returned to grace and favor? “Well, it’s a very strange thing to invite you down for Christmas if you’re not.

‘Don’t Write Me Off’

“Yes, I would hope to serve again. It is that simple. So don’t write me off.” The grin was quite cheeky. “Either from captaincy of the England cricket team or the premiership.”

Meanwhile, his half-dozen careers continue.

Archer was in Los Angeles last week to promote “A Twist in the Tale” (Simon & Shuster: $17.95), his second volume of short stories. A maiden play, “Beyond Reasonable Doubt,” is 600-performances strong and a second, with Paul Scofield to star, is in rehearsal. And Archer continues to speak (“we’re getting 40 invitations a week”) for the Conservative Party in Britain.

Then there’s his Playhouse Theater in London’s West End to tend, squash to play, self to constantly promote, a summer’s cricket to anticipate, more paintings to acquire and a collection of first editions to fondle. “I have the compleat Dickens, the compleat Scott Fitzgerald, the compleat Hemingway and the compleat Henry James. . . .”

Archer’s own life, it seems, is almost as compleat.

Not too long ago, it was perdition.

“I think it was youth,” he says now. But not with absolute conviction. “I hope it was. Naivete. I trusted people. Too much too soon, possibly. I entered the House of Commons too young, I think.”

In truth, Archer, at 29, was famous as the youngest member ever elected to Britain’s Parliament. Five years later, he was notorious as the youngest to quit, resigning his seat in 1974 as a gesture of honor after losing $620,000 in the collapse of a Canadian industrial cleaning company in which he had invested heavily.

He was drowning in debt, married with children and unable to find much call for an unemployed politician and self-taught publicist whose only real track record was that of a collegiate and Olympic sprinter.

So Archer followed past pragmatic form and settled on another career for which he was completely untrained: writing.

“Not a Penny More, Not a Penny Less,” published in 1976, concerned four men caught in an investment scam. It became a best seller in Britain and the United States.

“Shall We Tell the President?” was next. With it, an international faux pas . Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis quit her editing job at Viking Press to protest its publication of the novel, centered on a plot to assassinate Sen. Edward M. Kennedy.

But the book earned Archer $750,000 in paperback and movie rights. It was his reprieve from overdrafts, rented flats and canceled credit cards. It also set his talent and reputation for a stock literary formula--wealth, power and intrigue with human weakness directing the outcome. With coincidence and irony the final determinant.

Somerset Maugham. Guy de Maupassant. Charles Dickens. O. Henry. They all told rich, rolling stories. Archer added his imaginings to their mechanics. His philosophy: “Where I come from in the West Country, we say: ‘Tell ‘em a yarn, m’dear, and make ‘em keep turning the pages and you won’t be far wrong.’ ”

In 1980, he told ‘em the yarn of “Kane and Abel.” It was a saga of old money and new Americans through a tale of two families. His public on both sides of the Atlantic couldn’t stop turning their pages and Archer’s breakthrough book sold 250,000 in hardback and 4 million in paperback and was made it into an 8-hour miniseries by NBC.

“The Prodigal Daughter,” a story of America’s first woman President was published in 1982. With it, Archer became the first British author to sell 1 million copies in a single year. More than Le Carre. More than Fleming. More than King Dickens.

“First Among Equals,” a nostalgic, tragicomic exercise based on his own experiences and ambitions in the House of Commons, was published in 1984. It was first among equals on the New York Times best-seller list and remained there for 24 weeks. It also became a television miniseries.

And when all was apparently forgiven, if not quite forgotten, Archer’s political comeback was mighty. In 1985, Prime Minister Thatcher appointed him deputy chairman of her ruling Conservative Party.

Yet that recovery lasted barely one year--until two British newspapers reported Archer’s involvement with a London prostitute.

His second political resignation was immediate.

In a public statement, Archer denied any sexual relations but acknowledged giving the prostitute money to leave the country “in the belief that this woman genuinely wanted to be out of the way of the press.” Then he filed libel suits against that press.

He won $800,000 in damages and $1.2 million in legal costs from The Star. The News of the World settled out of court for $80,000, legal fees and a public apology.

Archer donated most of the money--the largest libel award in British history--to charity. “The major one was Ely Cathedral,” he said. “I think I am the new roof.”

It was a large and expensive lesson for British journalism, and a deeper moment of learning for Jeffrey Archer. He saw, he said, that his huge trust of people had become a blindness. He also had been made vulnerable by a willingness to risk, his writer’s restlessness and a genuine need to experience life to better understand its vitalities.

“I was bloody annoyed to have my career interrupt-ed . . . but after the trial I thought: ‘I mustn’t become cynical because that would be terrible,’ ” he remembered. He is blazered, French-cuffed and groomed not to distract the conversation. “ ‘But I must be more circumspect and careful.’ I think I have been since then.

“There hasn’t been a story in the press for the last three years that I would describe as risque. I don’t intend there to be one in the future.”

His business investments, he said, are safer now. At cocktail parties, he no longer hugs or flatters the ladies. The change, he continued, was noted during a lunch with Sir David English, editor of the London Daily Mail.

As Archer remembered it: “He said: ‘For God’s sake come back (to politics) quickly, Jeffrey. We’re not selling enough papers.’ ”

In the light of previous sexual excursions by heftier politicians--from Napoleon through Edward VII to Gary Hart--Archer’s encounter might be seen as a squall in a teaspoon. Especially by him.

“The French don’t understand them (political sexploits) at all,” Archer continued. “The Gary Hart situation had to be explained to (French President Francois) Mitterrand three times because he couldn’t work it out.”

Yet if his escapade was more peccadillo, why the high public indignation?

“I don’t think there’s indignation at every (public) level, funnily enough,” he said. “I think there are many senior politicians--not the least among them the Prime Minister of Great Britain--who take it for what it is worth.

“If every single politician who had ever had a mistress was removed from public office across the world, there would be an awful lot of by-elections tomorrow morning.”

Then why did he remove himself from office and not follow the public advice he once offered Gary Hart: Tough it out?

“Because at the time, I felt very strongly that we were so near to a general election that it (scandal) could only harm,” he said. So he remembered the words of Irish nationalist and Member of Parliament Charles Stewart Parnell. “He said: ‘Resign, clear your name, return.’ And that was only after a divorce.”

But all in all, he agreed, the resignation doesn’t seem to have left permanent verdigris. His 24-year marriage remains firm. Whatever he writes sells. Wherever he says makes for instant talk shows.

Archer’s critics remain as many and as predictable as his supporters. What is pushy and ambitious to some, is enthusiasm and determination to others.

He is a sardonic smart mouth, a blatant self-promoter, claim some, and, noted Peter Riddell, political editor of London’s Financial Times, “He is rather too flashy, rootless and smooth, lacking any real political substance.”

An English Gentleman

He is dash, style and fresh humor, say others, and, commented Judge Sir Bernard Caulfield at the conclusion of the libel trial, an exemplar of the English gentleman “worthy and healthy and sporting.”

Archer, of course, frets all the way to Lloyd’s Bank. Yet he cares passionately about his writing.

He believes it is improving. He considers “A Twist in the Tale” better writing than “First Among Equals.” But the best, he senses, is yet to come.

“I think I’m more courageous,” he said. “A lot of writing is self-confidence, the confidence to do something. Graham Greene once wrote of a bar in Soho and that two men sat at a table large enough to hold three whiskeys.

“It takes tremendous courage to write a sentence like that. I immediately knew the size of that room. I got the whole feel from that sentence alone.”

He improves from his own reading, from searching out the learned (such as the professor of English at Washington University who reviewed “Kane and Abel”) and from dissecting the classical storytellers.

“People are always writing to me and asking: ‘Should I write a spy story or should I write a love story?’ ” he said. “I always say: ‘Purchase a book by someone named Jane Austen and you will realize that you don’t have to go within five miles of your home your entire life to write a damned good tale.’ ”

He has borrowed from Fitzgerald’s writing notes on how an author should kill a character. It cannot be done by labored description. It must be done with a sentence.

“So (in “Kane and Abel”) I just wrote this one sentence,” remembered Archer. “ ‘Matthew died on a Thursday, 40 pages still to read of “Gone With the Wind.” ’ “

“There was nothing else to say about this man. It summed his whole life up.”

He has learned not to dictate readers’ images.

“Never announce the ability or inability of your characters,” he explained. “A reader must follow you for 10 pages and have discovered all those things. You must not say a character is tall or good-looking. But you must leave no one any doubt that he bent when he came into the room.”

Archer kneads no sex, violence, nor profanities into his prose. If that was good enough for Fitzgerald, he says, it certainly is good enough for him. So he recites from Fitzgerald: “ ‘When their eyes met they made love as they would never make love again.’ It makes me want to tell Harold Robbins you don’t have to have them tearing off their knickers and taking cocaine.”

Archer’s research is rarely by the book and mostly by plumbing the experiences of others and the doings of himself. It shows in “A Twist in the Tale” where 10 of the 12 stories have roots in actual events. And his critics, he accepts, have been fair, albeit backhanded in their commentaries.

Writing in the London Spectator, David Sexton discussed stereotypes set in mechanical plots as Archer’s “prime asset” as a novelist. “At no stage is the reader burdened by anything complex or original; the book is never so troublesome as to demand thought.”

Victoria Glendinning of the London Times Literary Supplement, said Archer’s fiction, as with all fantasy literature, is “regressive and conservative, set in the past or future but never for long in the intractable present.”

On the surface, Archer is royally confident.

He is flattered that some critics see his writings as “old-fashioned” and “simplistic” for he is both. He also is altruistic, patriotic, loyal, idealistic “and I will go to my grave believing in those things.”

Within Jeffrey Archer there is a fine, constructive dissatisfaction.

He is aware that his formal education was a loaf through light studies at Oxford and “I regret not having read say, the classics, and not having come out of Oxford with a double first (degrees).

“Just to start the game. You know, before we start rolling the dice, let’s get a double first. However, there will be those who will say to me: ‘If you had, you’d never had done anything you did, you’d have gone straight back to Oxford and taught for the rest of your life.’ ”

He is concerned with his reputation--personal, political and professional--and would hate to be judged at 48.

“That has to be when you’re 80 and people can see the ups and downs and the whole thing in context,” he said. “If the prime minister had been judged during her period as secretary of state for education, it would have been a very smaller victory and it wouldn’t have been very flattering.”

So Archer has 32 years to find his final form and by a route suggested by Longfellow. Voice descending to a Richard Burton baritone, he recites again: “The heights that great men reached and kept were not attained by sudden flight. But they, while their companions slept, were toiling upward in the night.”

Archer, fervently, hopes that future toil will change his “Who’s Who” description from “author-politician” to “politician-author.”

This political hybrid (his self-portrait states: “Social liberal and a fiscal conservative”) also is searching for some fierce challenge, to be a captain, to tap himself and team to their hobnails . . . as Peter Ueberroth was tested by the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

“I would love to run the Olympic Games if they came to Britain, I would love to do what Peter Ueberroth did,” Archer continued. He is intense, gleaming. “I’d be the commander in chief carrying all the risks and the responsibilities.

‘Every Bit of Energy’

“That would require every minute of six years, every bit of energy, every one of your ideas and all of your enthusiasm to make it as good as Seoul or Los Angeles and that one inch better.”

Archer was at the Closing Ceremony of the Los Angeles Games. He spotted Ueberroth. He examined him through binoculars.

“I thought: ‘You are a king. And against all the odds, Ueberroth.’ ”

For the time being, however, Archer is happily settled as co-commander of his own household and family holdings. It includes wife Mary, a former professor at Cambridge University, two teen-age sons, a flat on a Thames embankment and that country seat known as the Old Vicarage.

“My wife is still the most interesting person I know and much brighter than me . . . damn her,” he said. The curse is cushioned by a huge schoolboy grin. “But I remember early in our career as a married couple I used to regularly ask her what words meant.

“I’m delighted to say it is down to once a year now instead of once a week.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.