N.Y. STAGE REVIEWS : Return of the Buttoned-Down Play

NEW YORK — Whatever happened to the civilized play, the kind that Philip Barry and S. N. Behrman used to write, wherein well-dressed people made shrewd observations over dry martinis?

It went out of style 25 years ago, just as social behavior was starting to go free-form. No manners, no comedies of them.

But the times are changing. Just as a Yale man enters the White House, three new plays in New York offer heroes who attended good schools and know how to behave in restaurants.

Call it the return of the buttoned-down play: the play about well-spoken people with golden problems. Not “How am I going to pay the rent?” but “How am I going to fulfill myself?” We are reminded of the hero of Barry’s “Holiday” (1928). We may even think of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit.

Each play sees its hero’s progress rather solemnly. Luckily, each play also offers funny secondary characters and shrewd social observation.

For instance, A. R. Gurney’s “The Cocktail Hour”--first seen at the Old Globe Theater last summer--features Nancy Marchand as an upstanding Buffalo matron who slugs down six or seven martinis before dinner every night under the sincere conviction that she is having “just a splash.”

This line could become a running gag in Manhattan drinking circles, just as a crack from Richard Greenberg’s “Eastern Standard” has already become a classic with local foodies. It comes in the first act, when a bright young man (Peter Frechette) successfully flags down an attractive server-person in a midtown restaurant thus: “Oh, actress.”

Wendy Wasserstein’s “The Heidi Chronicles” also comes up with plenty of smart remarks as it follows an art historian named Heidi Holland (Joan Allen) through 25 years of wavering female independence. This play’s most-quoted line comes at a consciousness-raising session in the 1960s, when Heidi learns from her feminist sisters that there are no two ways about it--”Either you shave your legs or you don’t.”

Being a civilized heroine, Heidi wishes that there were two ways about it. On the one hand, she believes in the women’s movement. On the other hand, she doesn’t want to lose touch with her male friends, including one whom many a liberated woman would regard as an authentic pig (Peter Friedman).

Heidi wants it all: her ideology and her support system. That’s a characteristic stance in all three plays, which is why seeing them on three successive evenings is a bit like eating too many vanilla cookies--particularly when you’ve just come from a play as vigorous as August Wilson’s “The Piano Lesson” in Chicago. Drama at its most involving is about choices and consequences. These characters seem committed to keeping their options open.

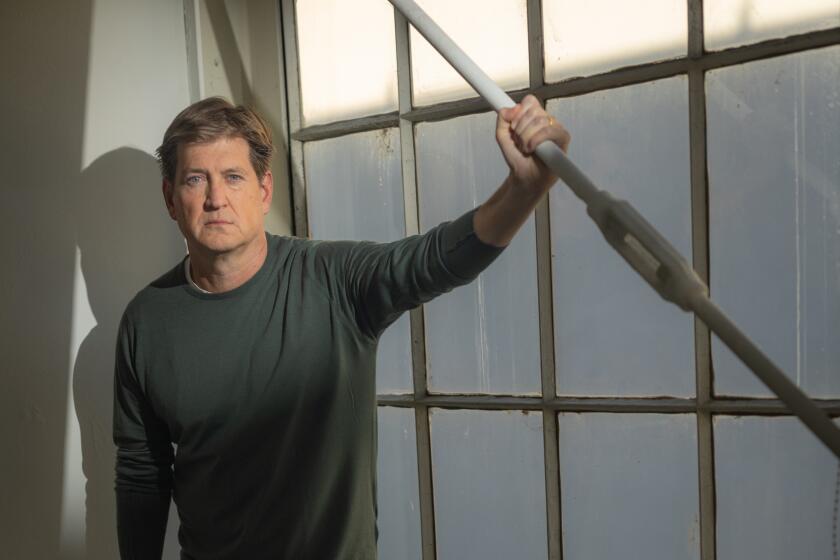

Gurney’s hero in “The Cocktail Hour” (Bruce Davison) is a playwright. He has returned to Buffalo to show his parents his latest script, which unveils some mild family secrets. If they feel traduced, he will withdraw the play. . . probably.

Greenberg’s hero in “Eastern Standard” is a brilliant young architect (Dylan Baker) who has arrived at his mid-life crisis 15 years early. “I hate my job: All I get from it is money,” he sighs. Perhaps he should design homes for the homeless. Or would that be cynical in the Hamptons?

Would it be fair to call these people wimps? Greenberg’s architect certainly qualifies. He appreciates his plight so sensitively that there’s no need for an audience to. One is tempted to applaud when a bag lady (Anne Meara) makes off with his and his trendy friends’ valuables. This guy needs to be dumped down in the Port Authority bus terminal with $2.75 and told to survive for a week. That would be a play.

We also get impatient with Gurney’s hero in “The Cocktail Hour.” “I don’t think you ever loved me, Pop,” loses poignancy when the speaker is getting up toward 40. Robert Anderson’s “I Never Sang for My Father” said everything that “The Cocktail Hour” says about rigid fathers and sensitive sons, and went beyond the saying to some doing.

Wasserstein’s “Heidi” isn’t a wimp so much as a watcher. Partly it’s professional detachment, partly it’s self-protection, partly it’s stubbornness. Heidi isn’t going to give herself to anything that isn’t worthy of her.

At the same time, she’s available to all her friends--almost too sensitive to their ups and downs over the years. We can see her go cold at a power lunch with a TV executive to whom the women’s movement has become something to base a sitcom on. Heidi can remember when the executive (Ellen Parker) was her best friend.

Characteristically, she doesn’t end the friendship. Heidi won’t desert anybody--one of her big problems and one of the reasons we like her. She will always feel “stranded” by the women’s movement (or any movement), but by the end of the play, she has found a purpose, a terribly traditional one, and it becomes her.

Heidi also smuggles us into some hilarious social gatherings, including an expensive wedding reception at the Hotel Pierre where the guests stand around sipping champagne and wondering what the groom (the aforementioned pig) sees in the bride. Definitely, the buttoned-down play is back.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.