Science / Medicine : Answers from Antiquity : A scholar and a scientist combed through ancient scrolls that resulted in new findings about Earth’s rotation and the dawn of Chinese civilization.

- Share via

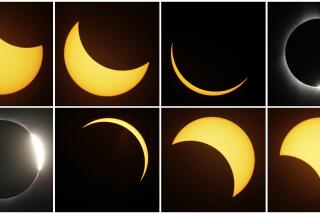

Buried deep in an ancient Chinese book called “The Bamboo Annals” is a passage about an unusual double dawn nearly 2,900 years ago: “In the first year of the reign of King Yi, in the first month of spring, the sun rose twice in Zheng.”

The passage describes what is believed to be a solar eclipse viewed in the 9th Century BC from the now-dead city of Zheng.

For centuries, scholars have seen this terse report as a strange but minor part of the annals, an ancient history book discovered by grave robbers 1,700 years ago.

But from this passage, Chou Hung-hsiang, a professor of Chinese at UCLA, and astronomer Kevin D. Pang of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory launched an unusual two-year search that has led to a series of findings about the Earth’s rotation and the dawn of Chinese civilization.

By matching Chinese astronomical records dating back 3,900 years with computer simulations of the movements of the Earth and moon, they have determined the rate of the planet’s gradually slowing rotation within thousandths of a second.

Their report was published recently in the British journal Vistas in Astronomy. While other researchers have done similar studies using Arabian and Babylonian eclipse records, none have been able to go as far back into history as Chou and Pang.

According to their research, the length of a day was 22-thousandths of a second shorter in AD 532, 42-thousandths of a second shorter in 899 BC, and 70-thousandths of a second shorter in 1876 BC.

Using the same method, the two researchers believe they also have established or confirmed the dates of several events in Chinese history.

Their research focused on the period when China was divided into the Shang, Zhou and Xia kingdoms, known collectively as the Three Dynasties. Scholars have never been able to determine the exact time of their rule and many question whether the Xia Dynasty even existed.

But by matching astronomical records with historical accounts, Chou and Pang believe they have determined the reign of several rulers in the Three Dynasties period and the beginning of the legendary Xia Dynasty.

Chou and Pang began their search after hearing about research to determine the planet’s rotational speed using Arabian and Babylonian eclipse records.

They knew the same could be done with Chinese accounts, and that it would take the research much further back into the past.

Out of thousands of eclipses recorded over the centuries, they chose three that fell outside of the years covered by Arabian and Babylonian accounts.

The first step was to determine an approximate date for the eclipses, since there are no recorded dates in Chinese history before 841 BC.

In the case of the double dawn, the task was easy, since King Yi was only two generations removed from that time. By assigning 30 years for each generation, they estimated the first year of King Yi’s reign to be around 901 BC.

By using JPL’s computers, they simulated the movement of the Earth and moon backward through time toward the double dawn.

While they found hundreds of eclipses within a century of that date, there was only one, which occurred on April 21, 899 BC, whose path was in line with the city of Zheng.

“You could go forward 2,000 years and backward 2,000 years and you wouldn’t find another one,” Pang said.

There was one problem: If they assumed each day was exactly 24 hours, the eclipse should have occurred 5 hours and 48 minutes later and would have been seen in the Middle East instead of China.

The discrepancy was caused by a phenomenon that astronomers have long known about: that each day, in fact, is not exactly 24 hours long. Because of atmospheric friction, tidal action and the movement of molten rock in the Earth’s core, the planet’s rotation has been gradually slowing, meaning that days were slightly shorter in the past.

To put the eclipse over Zheng 2,900 years ago, Chou and Pang calculated that a day had to have been 42-thousandths of a second shorter than today.

Using the same method, Chou and Pang analyzed an eclipse recorded in the 1,400-year-old History of the Northern Wei Kingdom.

“In the first year of the tai-chang reign period (of the reign of King Chu), on the day xin-you (the 58th day in a 60-day cycle), or the first day of the 10th lunar month, the sun from beneath the Earth eclipsed and began to wane from the southwestern horn.”

They set the date of the eclipse at Nov. 13, AD 532, and calculated that the length of the day was 22-thousandths of a second shorter than today.

The final eclipse that Chou and Pang studied is the oldest recorded in Chinese history.

According to the 6th Century BC “Book of Documents,” a compilation of historical treatises on the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties, the eclipse took place during the fifth year of the reign of King Zhong Kang, the fourth king of the Xia Dynasty.

“On the first day of the last month of autumn, the sun and the moon did not meet harmoniously in fang (the fourth lunar mansion). The blind musicians beat their drums and the lower-ranked officers and common people bustled and ran about.”

The passage provided several important clues. The eclipse was seen in a part of the sky known as fang, which roughly corresponds to the location of the constellation Scorpio. It was viewed in the last month of autumn, which in the Xia calendar is the same as modern month of October.

The computer again found hundreds of possible eclipses within a few centuries of the estimated date of King Zhong Kang’s reign.

But only one was visible from China during October and located exactly in the fourth lunar mansion of fang. “It satisfied all the criteria,” Pang said. “It was the only one possible.”

Pang and Chou set the date of the eclipse at Oct. 16, 1876 BC, which would put the beginning of King Zhong Kang’s reign in the year 1881 BC.

There are no other eclipses recorded before King Zhong Kang’s time, but there was an unusual clustering of planets that allowed Chou and Pang to journey even further back in history to the origins of the Xia Dynasty.

The five-planet conjunction, described in the Gu Wei Shu, a 2nd Century BC compilation of astronomical writings, was of one of the most spectacular in recorded history.

“During the reign of King Yu (first king of the Xia Dynasty), five planets lined up clearly like a string of pearls, brightly burning like joined jade disks.”

Chou and Pang ran a computer simulation of planetary orbits back through time and found that Jupiter, Venus, Mercury, Mars and Saturn did indeed cluster in the sky above the Xia capital of Yangcheng on Feb. 23, 1953 BC.

“It has never been that close and never in that straight a line,” Pang said. “You could put your thumb up and it would block them out.”

Their simulation matched a previously published report by David W. Pankenier, assistant professor of Chinese at Lehigh University, that proposed 1953 BC as the beginning of the Xia Dynasty.

“It could be very exciting if we finally know the beginning of Chinese civilization,” said K. C. Chang, professor of Chinese archeology at Harvard University. “Their findings are of great interest.”

Chou and Pang believe they will be able to date a few more points in the chronology of the Three Dynasties using other Chinese accounts of astronomical events.

Pankenier has already used a similar technique to date two other planetary conjunctions that he believes establishes the fall of the Shang Dynasty shortly after 1059 BC and the end of the Xia Dynasty around 1576 BC.

But modern researchers are far from unanimous in accepting any of these dates.

David S. Nivison, a retired professor of Chinese philosophy at Stanford University and an expert on the chronology of the Three Dynasties, said that using ancient Chinese texts is fraught with problems.

Erroneous words have been copied into the texts, events have been distorted for symbolic purposes, and efforts by ancient historians to reconstruct the past have created gross errors.

Compounding this problem is that most historians have only a limited understanding of astronomy, and most astronomers have little skill in wading through the complexities of ancient texts.

But despite the problems, Nivison and others say that using modern astronomical techniques to date the past holds enormous promise and, except for the discovery of new archeological finds, may be the only way to recover the long-lost chronology of the Three Dynasties.

“I think there is going to be a lot more agreement in the future over dates because of the use of scientific methods,” Nivison said. “But don’t underestimate the ability of scholars to argue and argue and argue.”