Exhibit Highlights Theater Designer’s Career

Theater designers, those artists who create the sets and costumes for the performing arts, face a peculiar situation unknown to their creative cousins in the fine arts, whose talents in painting, sculpture, even architecture, the theater designers combine.

Like painter, the designers create images both realistic and abstract. Like sculptors, they create objects that are three-dimensional and free-standing. Like architects, they create at least the appearance of cities and building facades, and their structures must be engineered so they don’t collapse and injure people.

With all this, the costume design aspect only complicates the theater designer’s responsibility, demanding a combination of talents unexpected of other artists.

However, unlike other artists’ works, the theater designer’s art achieves its full realization not in the quiet timelessness of a gallery or museum exhibition but in the often frenetic and always ephemeral context of a performance in which the design is but one element serving in combination with action, dialogue, dance or song, all of which constitute distractions if one wishes to look at theater design as an art in its own right.

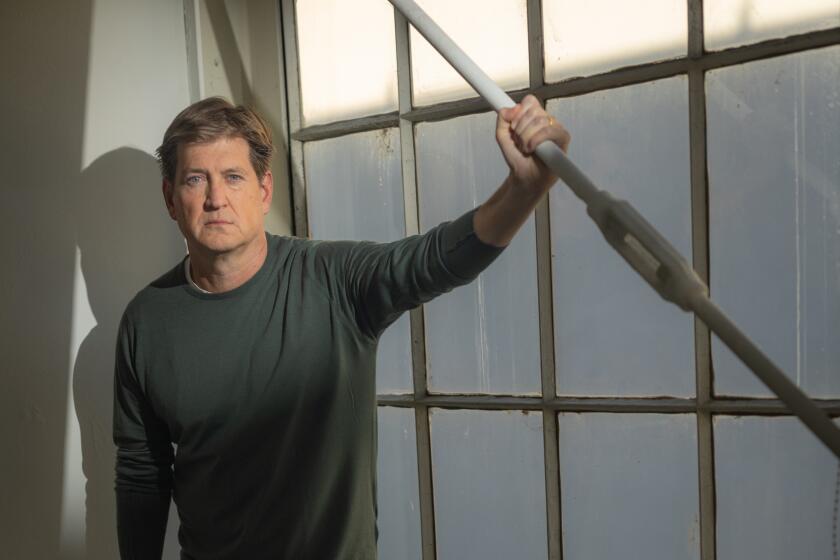

This situation defines a kind of built-in frustration inherent in “Robert Israel: A Decade of Theatre Design,” at UCSD’s Mandeville Gallery (through April 9). On view are 57 drawings, paintings, photographs, blueprints, and costumes representing six major projects by Israel, an internationally known and widely honored designer who has been on the UCSD faculty since 1977 but will soon take a position at UCLA.

To look at the representations of any one of the productions as singularly exemplary and impressive relative to the others misses the point of the exhibition. It seems, in fact, that the show is set up intentionally to defy such an approach because it concerns itself more with presenting aspects of the design process than with trying to convey the final outcomes of that process.

Consider, for example, the presentations of Israel’s designs for “The Yellow Sound,” commissioned by the Guggenheim Museum and inspired by a previously unproduced 1913 libretto (or text) by Wassily Kandinsky, one of the giants of early modern art, with music by the contemporary composer Thomas DeHartmann.

The story evolves from Russian mystical sources and deals with the continuity of the sensual and spiritual aspects of human life. To realize the production, Israel had to develop the scenic and costume elements called for by the text and suggested by the music. In the 20 or so sketches and drawings that Israel produced, we see yellow giants that look tree-like, a beautiful flower that is a character in its own right, a leaning bell tower, images of boulders, and representations of forms described on the drawings as “vague creatures” and “imprecise figures.”

The overall suggestion of the images as a group is decidedly mythic, even primeval. But we never actually hear the sound of the music or see these designs in their ultimate realization at full scale, with accompanying dialogue and action. There aren’t even any photographs of the actual performance in progress, nor are any of the actual costumes displayed.

Apparently, this isn’t oversight or cheapness on the part of the exhibition organizers because, on the other hand, Israel’s work for Prokofiev’s “Fiery Angel” is presented entirely in photographs, while his designs for “Mahagonny”--an opera by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill--appears only through a set of 10 construction blueprints. Of Israel’s work for the Philip Glass opera “Akhnaten,” we see actual elements from the production itself, gold-leafed hawk and ibis masks, a silk gown and a headdress worn by the character of Nefertiti.

Five sketches of these costumes are on view, but no other drawings, blueprints, or photos of other aspects of the production, either its preparation or final form, are displayed. The focus is similarly concentrated in the representations of another Philip Glass opera, “Satyagraha,” an exploration of the evolution of Gandhi’s ideas of nonviolent resistance. On view are five drawings showing the various characters’ costumes, which consist of straightforward late 19th and early 20th century styles.

The realism of the imagery from “Satyagraha” contrasts sharply with the fantastic and unnerving creations for “The Yellow Sound,” which, in turn, displays a very different sensibility relative to the designs for “Akhnaten.” So, the exhibition steps not only from style to style in expressing the breadth of Israel’s responsibilities and creative as a theater designer. And it does this quietly and subtly, not with occasional dramatic images but with the sum of many images.

As to whether the works on view bear up to scrutiny as “art” independent of their descriptive and documentary functions, argument could be made either way. But there’s this: the drawings from “Satyagraha” are on loan to the exhibition from the collections of the Museum of Modern Art. Those from “The Yellow Sound” are on loan from the Levi Strauss & Co. Art Collection. And many other images and objects on view come from the Daniel Weinberg Gallery in Los Angeles and the Max Protetch Gallery in New York.

Clearly, the line between these images from the realm of theater design and more conventionally understood visual art is difficult to find, if it exists at all.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.