Jury Finds Kraft Guilty of 16 Orange County Murders : Verdict Stuns Suspect in 40 Serial Slayings

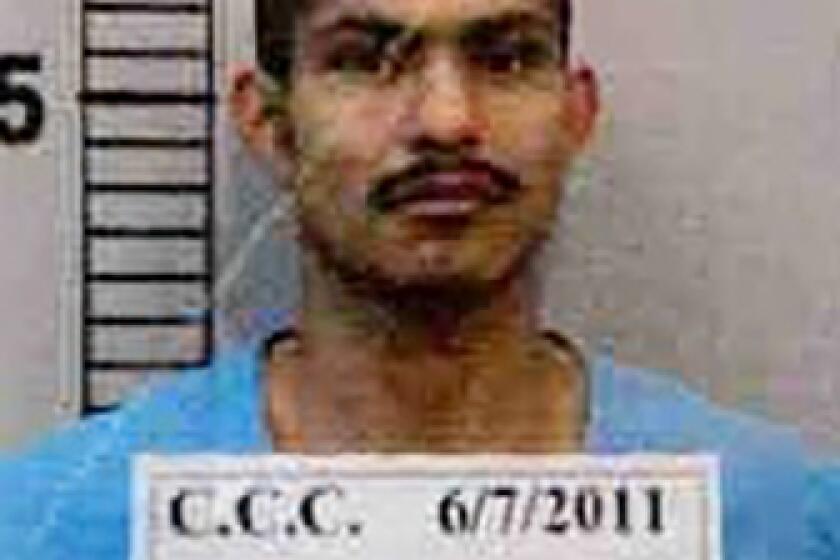

Randy Steven Kraft, a soft-spoken computer consultant depicted by prosecutors as perhaps the worst serial killer in U.S. history, was convicted Friday of murdering 16 young men in Orange County over a span of 11 years.

Authorities believe that Kraft has killed more than 40 men in California, Oregon and Michigan, in most cases picking up young hitchhikers, disabling them with drugs or alcohol, sexually mutilating their bodies and dumping them along freeways.

Kraft, 44, dressed in a brown tweed jacket, blue jeans and tennis shoes, appeared stunned when the court clerk read the first “guilty” verdict. It was for Edward Daniel Moore, the first of the 16 victims, killed in 1972. Kraft’s lawyers had considered Moore and some of the earlier victims their only real chance for any acquittals. Kraft shook his head after two more guilty verdicts were read, then began taking notes.

Families of victims broke into tears as they heard the verdicts. Judy Nelson of Westminster, whose 18-year-old son, Geoffrey Alan Nelson, was killed in 1983, hugged her daughter and her sister, and they burst into tears when the clerk reached her son’s name.

She later said that the mothers involved “had 16 beautiful sons, and that guy destroyed them. He should pay.”

Two of Kraft’s sisters and a niece sat in the back of the courtroom in disbelief.

“I’m shocked,” said Kay Plunkett, a schoolteacher who testified for her brother. “It’s a long way from being resolved.”

Judge Donald A. McCartin asked lawyers in the case to return Tuesday to set a date to begin the penalty phase of the trial. At that time, prosecutors will introduce some of the other 29 murders they have linked to Kraft, including six in Oregon and two in Michigan. Prosecutors will ask for the death penalty. The jurors’ only alternative would be a lesser sentence of life in prison without parole.

Kraft’s attorney, C. Thomas McDonald, said after the verdicts were read Friday that Kraft’s private reaction was “utter disappointment, of course.”

The verdicts came 6 years to the very week after Kraft’s May 14, 1983, arrest when two California

Highway Patrol officers found a dead Marine--25-year-old Terry Lee Gambrel--in the front passenger seat of Kraft’s car.

“Excellent verdicts,” said Chief Deputy Dist. Atty. James G. Enright, who said he had no regrets that his office had decided to try Kraft on 16 murders. That decision brought strong criticism from those who thought it would result in an unnecessarily long and costly trial.

“We did the right thing. How could you leave any of them out?” Enright said.

The 10 women and two men on the jury, who remained sequestered during their 11 days of deliberations, found Kraft guilty of first-degree murder on all 16 deaths in the charges, plus one count of mayhem and another count of sodomy. The only not guilty verdict was on a single sodomy count.

The jury’s decision Friday brought to a close the first phase of a gruesome, 9-month-long trial in Santa Ana that subjected the jury to day upon day of pictures and evidence of the bruised and battered victims. Courtroom proceedings centered on the jargon and details of human pathology, of Kraft’s meanderings in the world of Southern California’s gay bars and of his driving--impulsive, nighttime excursions up and down the freeways.

“I like to drink and drive,” Kraft told Long Beach police in 1975, saying that he “really got into one of my driving fits” on the night he was last seen with one of his alleged victims.

Described as a quiet, well-liked businessman who enjoyed walking his dog, Kraft, by some accounts, lived a normal existence in a small Long Beach bungalow he shared with another man. “There has always been just one issue in this case: whether Randy killed these boys because he is sick, or because he is just biblically evil,” said one lawyer who knows Kraft personally.

Kraft, 44, who did not testify at his trial, has denied killing anyone.

“I don’t belong here,” he said in an interview with The Times from Orange County Jail a few months after his arrest.

Legal experts say the massive effort put together by Kraft’s three lawyers to defend him against so many murders is likely to make the his case the most expensive criminal proceeding in the state’s history. Several legal experts familiar with the case have estimated the cost at a minimum of $10 million.

Kraft’s case is also unprecedented statewide because of the 45 deaths linked to him. Up to now, California’s most prolific mass murderer has been Juan Corona, twice convicted of murdering 25 itinerant farm workers whose bodies were found buried in fruit orchards near Yuba City in 1971.

The Kraft accusations total more than the number of victims linked to Ted Bundy (36 to 44 by various law enforcement agencies), who was recently executed, or John Wayne Gacy Jr. in suburban Chicago (33).

Donald Harvey, a 38-year-old hospital worker from the Cincinnati area, pleaded guilty in Ohio and Kentucky in 1987 and 1988 to 37 murders, mostly patients where he worked. But Harvey has claimed that he committed half a dozen other murders which have not been verified.

On the night he was pulled over for erratic driving on northbound Interstate 5 in Mission Viejo, Kraft was found with the dead Marine, who had been strangled with a belt, like most of the other victims. Faint marks on his wrists indicated he had been tied with shoelaces, like many of the others.

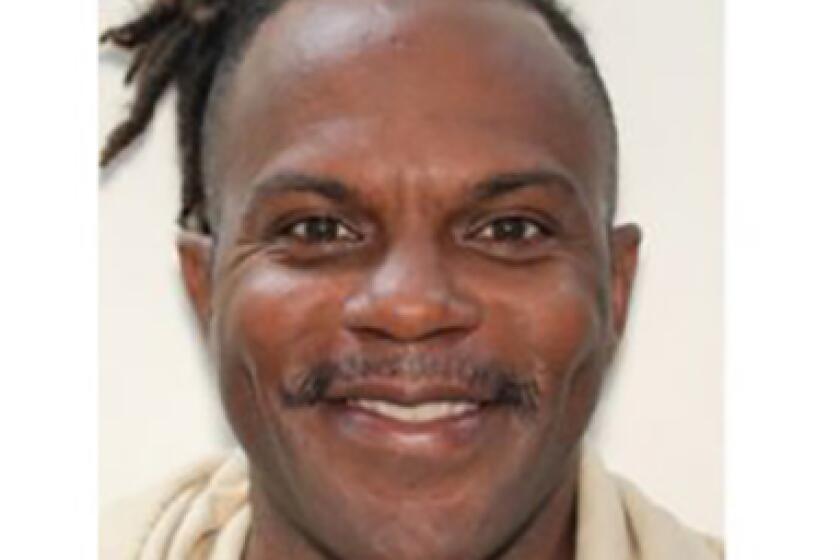

Evidence found in Kraft’s car convinced Orange County Sheriff’s Department investigator James A. Sidebotham that he was the serial killer local police had been seeking for nearly 12 years.

Also, Sidebotham would say later, the car was a “virtual drugstore” of prescription vials for pills matching the drugs found in many of the victims.

The most damning evidence was color photographs of some of the victims, found under the floor mat on the driver’s side. The men were depicted in nude poses and appeared to be unconscious or dead. One victim was shown with a strangulation mark on his neck, with his wrists tied with a shoelace.

The most spectacular evidence, and the most controversial subject at the trial, was the list in Kraft’s handwriting found in the trunk of the car. A quick glance at the list convinced Sidebotham and others that it was a “death list.” To their amazement, it had 61 entries. And at least five of them appeared to investigators to represent double murders.

Sidebotham, who sat in the back of the courtroom when the verdicts were read Friday, had told Kraft in a videotaped interview the morning of his arrest: “We’re going to get you, Randy. Whether it’s on 10, or 20, or 30, we’re going to get you.”

At the time of Kraft’s arrest, neither Sidebotham nor other investigators of serial killings in Southern California had heard of him. He hadn’t been on any of their long lists of possible suspects. So they were surprised to learn that Kraft at one time was a suspect in a Long Beach murder.

Keith Daven Crotwell, 19, had disappeared during Easter weekend, 1975. Crotwell’s friends had last seen him leave the parking lot of the Belmont Plaza in a car with Kraft, who later was questioned by Long Beach police.

Crotwell’s severed head was found in the water next to a Long Beach jetty, and his body, found in Orange County, was not identified until years later.

More than 30 of the murders linked to Kraft occurred after Long Beach police finally stopped actively working the Crotwell investigation.

In the intense investigation after Kraft’s arrest, Deputy Dist. Atty. Bryan F. Brown eventually decided to charge him with 16 murders within Orange County’s jurisdiction.

In eight of the 16 murders, Brown had evidence directly tying Kraft to the victims: photographs found in his car, fiber evidence, or the young men’s personal effects found at Kraft’s house. At one death site, Kraft’s fingerprints were found on a bottle.

In the other eight murders, the prosecution had to rely primarily on their similarities to the other eight, plus the list found in Kraft’s car.

Kraft’s lawyers were convinced they had lost the trial before it began. Judge McCartin had sided against them on their three key issues: They wanted the counts divided into three separate trials. They wanted the trial moved out of Orange County. They wanted the judge to prevent prosecutors from showing jurors the list from Kraft’s car.

“This verdict is actually just a logical result of the judge’s decisions before the trial,” Kraft attorney William J. Kopeny said.

Although most officials involved were uncertain that Kraft would be convicted on all 16 murders, both sides were sure that he would be convicted of enough murders that the heart of the trial would be the penalty phase.

The Kraft trial produced little spectator interest as one criminalist after another testified about blood-alcohol content, drug levels in the victims and trace evidence found on their bodies. But the courtroom was usually full on key days, such as the opening of the prosecution’s case and the defense’s case.

The jury began deliberating on April 28. According to the date on the verdict forms, they actually had reached their verdicts late Thursday. The jurors indicated to the judge as soon as they arrived Friday morning that they probably would be ready shortly.

Some legal observers were stunned that they had reached a verdict because of the few times they sent notes asking the judge questions or had any testimony read back.

Thursday afternoon before the verdicts were announced, another Kraft attorney, James G. Merwin, said he was certain they would not be back any time soon.

McDonald said he was bothered that on at least nine of the 16 murders, the jurors made no inquiries at all.

“I’m afraid there were so many charges that they just had a snowball effect on the jury,” McDonald said.

Prosecutor Enright disagreed. He noted the not guilty verdict on the one sodomy charge, which was coupled with a “not true” finding that great bodily injury was involved in that case.

“I think that proves these jurors were looking at each case individually,” Enright said.

Yet, one law enforcement official theorized that the evidence against Kraft was simply so overwhelming that the jurors did not need to review much of the testimony.

“There were so many similarities in these murders,” he said, that “Kraft was either going to be convicted of all of them or none of them.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.