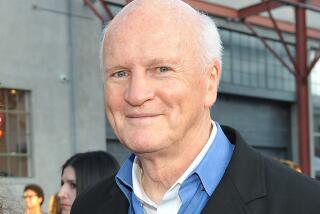

The Prince of Barter : For hotel magnate and art collector Arnold Ashkenazy, every day’s a high-stakes swap meet

- Share via

When Arnold Ashkenazy goes shopping for art to add to his 20,000-piece collection, insured for over $20 million, he rarely puts cash on the table. Hotel rooms, yes. Also airline tickets, jewelry, cameras, limousine rides, wine, televisions, Lakers tickets, VCRs and cruise packages.

But cash? Not if he can help it.

“Cash?” asked the impish Ashkenazy, 55, in mock horror. “Ah, but that would take all the fun out of it.”

Ashkenazy’s fun comes from buying art the old-fashioned way. He barters for it.

In the last few years he has obtained thousands of paintings and sculptures from artists in exchange for luxury accommodations, appliances and services.

“It’s like a game show, the way he buys art,” said one art dealer who rebuffed Ashkenazy’s approaches.

Another art dealer contacted by Ashkenazy, Joni Gordon of Newspace gallery on Melrose Avenue, said she was astounded that he wanted to trade with items he had garnered through his elaborate barter network. “What did he think?” she asked with a laugh, “that I just fell off the turnip truck?”

Ashkenazy’s methods and flamboyant manner may be looked on with disdain by many in the old-line art world, but he has struck a chord with young, often struggling artists (and a few who are well-established), offering them the chance to stay in deluxe hotels, call limousines on a whim and eat in expensive restaurants. He also gives them the chance to have their work seen by a wealthy clientele in a comfortable setting.

Ashkenazy’s “galleries” are the Westside luxury hotels--including L’Ermitage, Bel Age and Mondrian--that he co-owns with his brother, Severyn. There are abstract sculptures in front of the hotels. Paintings and prints hang on almost every available wall space in the lobbies, suites, corridors, function rooms, restaurants, bars and bathrooms. Even the swimming pools and sun decks are viewing spots for large paintings on enamel and more sculptures.

The art is not just for decoration; it is part of the Ashkenazys’ business operation--all of the art on display is for sale.

“You have to understand that we buy $3 million to $4 million worth of art a year,” said the more sedate Severyn, 53, admitting that he and his brother have an economic as well as aesthetic motivation where art is concerned. He said the barter system has kept their collection on a steep growth curve. “Who has that kind of money on hand? In this way we can continually build a collection that would otherwise not be possible.”

Even the 1986 Chapter 11 bankruptcy of Ashkenazy Enterprises--one of the biggest in Los Angeles County history--could not stop Arnold from making his appointed rounds of artists and dealers.

“I don’t think there was a month went by we did not buy a piece of art,” Severyn said.

“I don’t think there was a day, “ Arnold countered. “Not one day.”

The first Ashkenazy family art collection was almost completely dismantled in September of 1939, when the Soviet Union invaded Poland and sent troops into the city of Ternopol, where both brothers were born. When the soldiers came, Arnold was almost 5.

“I recall running up and down to save a few of the pieces we thought were in danger,” Arnold said over a cappuccino in the restaurant at Mondrian. “We didn’t realize that everything was in danger.”

Almost all of the important pieces in the collection, which Arnold said included works by Matisse, Monet, Gauguin, Picasso and Manet, were gone by the end of the war. The Ashkenazys, however, were happy just to survive those years. Izador Ashkenazy, the boys’ father, knew that Jews would be in mortal danger when the Nazis arrived in Ternopol. He used a hidden cache of gold coins to pay Gentiles to hide the family in the secret cellar of a country house.

At the end of the war the Ashkenazys made their way to France, where they prospered in the clothing business and began building a new art collection, and then to Los Angeles in 1957. With $100,000 borrowed from their father, Severyn and Arnold entered the real estate business, developing apartment buildings in the mid-Wilshire district and West Hollywood.

By the time he was 29, Severyn has noted in several interviews, he was a millionaire.

In 1978, the Ashkenazys entered a new business with the opening of L’Ermitage, an 111-suite luxury hotel in Beverly Hills named for the famed Hermitage art museum in Leningrad. Severyn spearheaded the family’s business ventures as they opened more hotels. Arnold stayed in the background, overseeing the family art collection, operating a gallery for a few years and, in the late 1970s, accumulating large amounts of art from dealers and auction houses. He bought originals by Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Raoul Dufy, Maurice de Vlaminck, Stanton MacDonald-Wright, John Altoon, Saul Steinberg and California Impressionist William Wendt, and lithographs by Joan Miro, Marc Chagall and Alexander Calder.

By the mid-1980s, the brothers were experimenting with placing their art into their hotels. “It was copies at the beginning,” Severyn said. “We were testing. We had to know if there would be vandalism, if we had to worry about stealing.” Assured that their art was safe, they began moving in the real art, including some of the most valuable paintings in their collection.

At one point, knowledgeable diners at the Cafe Russe atop L’Ermitage could ask to be seated at a table near both Van Gogh’s oil painting of the Nuenen vicarage and Renoir’s oil, “Les Toits De Ferme, La Rouche Guyon.”

Safety precautions included bolting the paintings into the walls and electronic alarms, and the Ashkenazys admit that security was always a worry. When the electricity went out one night in Beverly Hills, Arnold took security matters into his own hands. “I jumped out of bed,” he said, “ran to the hotel and went up to Cafe Russe, just to watch the door.”

Severyn said that decorating with fine art was well worth the added problems and costs. “I think with the advent of L’Ermitage,” he said, “hotels are now ashamed to hang garbage on their walls.”

In the early 1980s the Ashkenazys began an explosive development program to reap the expected benefits of the 1984 Olympics. As they opened more hotels and had more need of art, Arnold strove to buy in volume and make discount deals.

Local painter Cathleen Kaman, who signs her work “Beanie,” said that she made a deal with Arnold for 30 paintings. She said he is a formidable deal maker. “He’s the best,” Kaman said with a laugh. “He hits a deal from all angles.”

But she was not prepared for the angle he came up with when he approached her for more work. “He offered me jewelry and wine and things like that in a barter,” she said. “It seemed pretty bizarre. I wasn’t interested.”

With most of the Ashkenazy cash tied up in the new hotel projects, Arnold had turned to barter. He had, at his disposal, a basic bargaining chip--luxury accommodations--that could be used to tempt not only artists but other companies that could provide the airline tickets, appliances, jewelry and other items that could in turn be bartered.

Not all artists thought that bartering for luxury items was unsavory. “I saw my friend Fred Brathwaite in L.A. about four years ago and he was really living it up in a suite at the Mondrian,” said Jedd Garet, a painter whose star is on the rise in the New York art world. “I asked how he was able to afford all this, and he said, ‘Go see Arnold.’ ”

Arnold was glad to see him--the Los Angeles born-Garet was already garnering good reviews and publicity. “Arnold is a very good bargainer,” Garet said, “but I’m not too bad, either. He wanted me and I knew it.” Garet ended up trading him two paintings, which are now hanging in the Bel Age, for several thousand dollars worth of barter, which he has used mostly for hotel stays in cities across the United States and in Acapulco.

“It’s fun to stay in a hotel when you have a huge suite and don’t have to feel guilty about it,” Garet said. “The way I look at it, it’s like the money is already spent--it’s gone before I even see it.”

Garet is now negotiating with Arnold for another trade.

Eric Orr, a well-known local painter of luminous geometric forms, has used his barter credits primarily for accommodations for visiting friends. Painter Michael McCall got a VCR, answering machine, travel and Lakers tickets. Sculptor Herb Elsky, who fashions polyester resin into abstract forms, got a 19-inch television, a flight to Japan for his wife and the use of a ballroom at the Bel Age to hold a benefit event for Dharma Dhatu, a Buddhist group to which he belongs. Elsky named one of his traded sculptures, which sits in the restaurant at the Mondrian, “Ashkenazy Rock.”

A European painter who wanted to stay in Los Angeles past his visa expiration got the services of an immigration lawyer.

Many artists who did trade said they were happy with the deals they struck, although some pointed out that the price deducted from their Ashkenazy barter accounts for items such as televisions and VCRs was the full retail price. The same items were available at discount stores for far less.

The thorniest issue of all was taxes. The Ashkenazys said they make it clear to artists that the barter they receive should be reported at tax time as income, just as if they were paid in cash. But at least one artist who has done business with the Ashkenazys admitted not reporting bartered goods as income. “If the IRS comes looking,” said the artist, “a lot of us are screwed.”

Some artists were able to strike a deal in which they received at least partial payment in cash. Michael Todd, whose large steel sculptures can be found on the outside of several private and public buildings in Los Angeles, made a half-and-half deal.

“I had just bought a new studio about three or four years ago and I needed cash to renovate it,” Todd said. “I told them I had to have at least some cash.

“I think I am the only artist that got at least some money out of them.”

That’s not true, but those artists and dealers who did get cash from the Ashkenazys in recent years seem to believe they were the only ones to do so.

New York painter Mark Schwartz got some money initially. “I told them I needed to get art supplies and the barter system didn’t really have what I needed,” said Schwartz, who teaches at two high schools to make ends meet. “It’s good for jewelry and trips and expensive dinners, but I would have felt guilty if I traded my art for that. I could hardly afford supplies.”

After the initial part-cash, part-barter deal, Arnold told Schwartz there would be no more cash offers. “He told me I was the only artist who got any cash,” Schwartz said, “and that if I wanted to work with him next time it would be only barter.”

Some artists and dealers demand and get all-cash deals.

English artist Stefan Knapp recently completed a large enamel-on-metal painting made to fit a wall near the swimming pool at the Mondrian and is doing several other large-scale pieces to custom-fit outdoor spaces at the hotels. “Arnold kisses everyone and says he loves you, but to get anything out of them is very difficult,” said Knapp, speaking from his workshop in southern France. “But I don’t like barter. I told them I have to actually be paid.”

----

In January, 1987, almost five decades after the Soviets invaded Poland, it seemed as if the Ashkenazys would again lose the family art collection.

By then, the Ashkenazys’ principal hotel and real estate company, Ashkenazy Enterprises, had been in bankruptcy for almost a year. The filing of bankruptcy gave the brothers protection from their creditors while they renegotiated more than $100 million in loans and continued to operate the hotels. They remain in operation under Chapter 11 today.

Beverly Hills Savings & Loan, to which they owed more than $40 million, went after the art and obtained a preliminary court order allowing it to be seized right off the hotel walls. Neither the Ashkenazys nor the S&L; would discuss their negotiations in the wake of the court order, but they came to an agreement that left the Ashkenazys with the art and a restructured debt secured by property and by a group of about 50 of the artworks, according to Severyn.

The art helped them in other ways through their financial troubles. A number of paintings were sold--including some by Renoir, Braque, Dufy and Utrillo--to raise about $5 million, according to Severyn. “When they went, he cried,” Severyn said, gesturing toward his brother. “But we had to view it as part of our business.”

During the bankruptcy, they have managed to hold on to some of the big names. Still in the collection are the Van Gogh painting, appraised at $1.2 million as of 1985 and now in storage, and the Picasso “Buste D’Homme” oil, appraised about the same time at $166,000 and now hanging in the lobby of the Bel Age.

Also hanging in the hotels are original works by well-established contemporary artists such as John Altoon, Stanton MacDonald-Wright and Charles Arnoldi. All of them, Arnold emphasized, are for sale at the right price.

The days of Arnold going on buying sprees at the world’s great galleries and auction houses are over, at least for the time being. But he said he is content to concentrate on using barter to obtain works by less-known artists. With glee, he leafed through a catalogue of works in the hotels, pointing out artists whose work has doubled or tripled since he bartered with them (several of the artists confirmed that their selling prices have increased, although most said Arnold’s assessments of how much were optimistic).

“Our excitement now is to look and evaluate,” he said. “The financial excitement is still to come, to prove how right we were in buying this art.”

It’s clear that Arnold’s joy comes at least as much from the buy-and-sell game as from aesthetics. He would be the last to dispute this.

“Each and every one of the paintings is like a blind date,” he said, “ . . . a blind date to conquer.”

But as long as the Ashkenazy art collection is tied irrevocably with their businesses, the collection could vanish with another downturn in their fortunes.

Arnold shrugs his shoulders at the prospect of losing it all one day. “I will tell you what my parents told me, very wisely,” he said. “All earthly possessions can be replaced. Health, life, family, friends, beautiful people--they cannot be replaced.

“A painting is a painting, that’s all. It is not your friend, it is not your relative. If I lose one, I know where I can find one just as good.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.