Target of Bitter Lawsuits : Top Builder Is Accused of Shoddy Work on Homes

- Share via

Beverly Vedder was so upset by angry phone calls from homeowners that she occasionally broke down and cried.

“I was reduced to tears at times,” testified the former secretary for giant housing developer Kaufman & Broad. “I was overwhelmed.”

Of the many homeowner grievances that Vedder received, one especially stuck in her mind. It came from owners of a home in the Riverside area who complained that the bathroom floor in their new house slanted so badly that they had to hold on to the toilet to keep from sliding off.

That and similar complaints from other homeowners in the Riverside area were initially ignored by Kaufman & Broad, Vedder testified. She said company officials seemed to think that “if this was pushed aside long enough it would go away.”

The complaints have not gone away, however, and are now at the center of an uncommonly bitter and prolonged lawsuit between Kaufman & Broad--California’s largest builder of single-family houses--and dozens of homeowners in Riverside County.

Kaufman & Broad officials dismiss most of the allegations in the suit as sour grapes by disgruntled or misinformed former employees and characterize the Riverside litigants as fortune-seekers manipulated by unethical attorneys who are trying to capitalize on honest and fixable errors. The company maintains that it consistently builds quality houses at reasonable cost to fulfill the American Dream of home ownership.

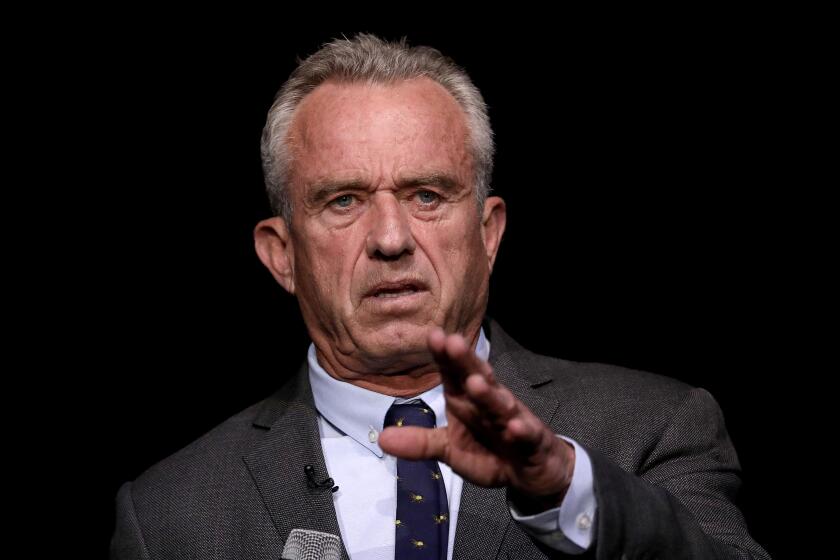

“The Riverside litigation is driven by plaintiffs with unreasonable expectations and fueled by greedy lawyers,” said company chief executive Bruce Karatz.

But accusations emerging from interviews and testimony under oath in depositions taken by homeowners’ attorneys in the 4-year-old lawsuit tell a story of dozens of dream homes gone bad.

It is a story that began with the promise of that increasingly rare commodity in California: quality housing for first-time home buyers at affordable prices. But, according to customers and former employees of Kaufman & Broad, the promise of quality was frequently compromised by fast-paced construction schedules, and homeowner complaints of shoddy workmanship often were ignored.

Privately, some construction workers laughed about the quality of the homes they were building in Riverside and even referred to them as a “joke,” according to the testimony of one former construction employee.

Dozens of homes were built in Riverside and neighboring Corona without proper plans and, when serious structural problems appeared, company officials tried to cover them up, according to sworn statements.

Gifts for Inspectors

In addition, Kaufman & Broad gave liquor and substantial gifts to building inspectors who were responsible for enforcing construction code standards, and one inspector from the city of Riverside approved homes without even looking at them in order to help the company meet its construction schedule, according to a sworn admission by the inspector and other sworn statements.

Homeowner litigation is common in the building industry, and it cannot be determined with certainty how the quality of Kaufman & Broad homes compares to those of other large developers. But the company has been at the center of a series of high-profile controversies.

The Riverside County lawsuit marks the fifth time in two decades that Kaufman & Broad has been accused of serious misconduct, ranging from bribery to substandard construction practices. The district attorney’s office in Riverside County is examining transcripts of witnesses’ testimony gathered in the civil case, but no charges have been filed.

FTC Probes Complaints

The Federal Trade Commission staff is also looking into complaints of shoddy building practices in connection with the Riverside suit, according to Thomas Massie, attorney with the FTC enforcement division in Washington. Kaufman & Broad is currently operating under a 1979 FTC consent order based on alleged substandard building practices.

Kaufman & Broad officials insist they have fewer problems than the building industry norm, saying that they have sharply increased the time and money spent on ensuring that buyers are happy.

The firm has built more than 175,000 homes worldwide in the last 32 years, fewer than 1% of which have problems, company officials say. The company contends that nearly a quarter of its buyers say they have gotten favorable recommendations from other Kaufman & Broad homeowners.

“We are not perfect, by any means,” company chief executive Karatz said. “Our products are built by hand, in the heat, rain and wind. This is a people business and people can make mistakes. In the vast majority of incidents, we take care of these mistakes quickly and to our customers’ satisfaction.”

The company has received numerous industry design, architectural and marketing awards in recent years. “For the volume they do, they’re an exceptional company,” according to Sanford Goodkin, a real estate consultant in San Diego.

Leading Builder

Kaufman & Broad Home Corp., as the Los Angeles-based company is now formally known, occupies an important corner of the California housing marketplace as a leading provider of shelter for the middle-class. Its customers are commonly young couples acquiring a home for the first time.

The company expects to build more than 4,000 homes this year statewide, largely in fast-growing, metropolitan areas. The prices average about $160,000 statewide, which is inexpensive by California standards.

Kaufman & Broad’s financial fortunes have never looked better. Profits have reached record levels and sales are expected to surpass $1 billion this year for the first time following a reorganization last year that turned Kaufman & Broad Home Corp. into an independently owned and operated company.

But the firm has a long history of serious problems, ranging from criminal convictions in Chicago in the early 1970s to homeowner lawsuits all over California in the 1980s.

One of the Chicago cases involved a former president of Kaufman & Broad of Illinois who pleaded guilty to bribing a federal building official with three cases of liquor while he was head of the company. In the second case, in 1973, Kaufman & Broad was fined $50,000 after pleading no contest to charges that the company was involved in bribing officials of suburban Hoffman Estates in a zoning change scandal.

Chicago Investigation

The company also was under such heavy fire from dissatisfied homeowners in the Chicago area that the Federal Trade Commission began an investigation into the firm’s building and sales practices dating back to the late 1960s.

Kaufman & Broad promised the public and its investors that it would do better. “We’ve learned our lesson,” company Chairman Eli Broad told a trade journal in 1972. “The industry has to increase its quality and learn to treat consumers differently.”

By 1979 the FTC had completed its investigation, and without admitting guilt, Kaufman & Broad signed an agreement that it would cease such practices as false advertising, building substandard houses and furnishing model homes with undersized beds to make rooms look larger than they actually were.

By 1980, the company was again in criminal trouble, this time in Santa Clara County Superior Court where it was fined more than $200,000 in connection with charges that it induced Milpitas city inspectors to falsify building inspection reports.

Cases of Liquor

Company documents obtained by authorities investigating that case indicate that Kaufman & Broad routinely offered cases of liquor to city, county and utility company officials with which the developer dealt in Northern California.

Kaufman & Broad officials admit that the company has had problems in the past, but they say they are ancient history and irrelevant. And they say they have fired any employees found guilty of wrongdoing.

“The company is as different today as . . . Chrysler is today versus 15 years ago,” chief executive Karatz said.

Fifteen years ago, Kaufman & Broad was a far-flung company with operations across the United States and Europe. But the firm has since cut back and now operates primarily in California and France.

“We thought it was impossible to meet a standard (of excellence) in multiple markets,” Karatz said. “We decided to focus on a few areas and do it well.”

Complaints Continue

Despite the new smaller-is-better philosophy, serious customer complaints have continued into the mid- and late-1980s, interviews and court records show.

In the Northern California town of Novato, for example, 88 townhouse owners are suing Kaufman & Broad, charging that their homes were so poorly constructed that many of them must be reframed and that whole walls must be ripped out and rebuilt.

Kaufman & Broad’s own building expert corroborated many of the homeowners’ complaints in a sworn deposition taken by the San Francisco law firm of Alexander Anolik, representing the homeowners.

The 1984 suit, concerning homes built in the early- to mid-1970s, is scheduled for trial this month, but Karatz noted that “lots of settlement discussions are going on.” He declined to discuss the homeowner allegations in the case.

But of all the complaints by buyers of Kaufman & Broad homes, perhaps the most acrimonious are the ones in Riverside County, where several lawsuits have been filed in recent years involving new housing tracts near the Riverside Freeway.

Bitter Standoff

Although some of the litigation has been settled in recent months, a major lawsuit remains in a bitter standoff. That suit, which involves 34 homeowners, is scheduled to go to trial next March.

Karatz believes the homeowners no longer want to fix the problems but are simply seeking “money, lots of it.” In related cases that have been settled out of court, the firm has agreed to fix the homes or buy them back at fair market value. Both offers also include compensation payments.

Karatz has also attacked the plaintiff’s attorneys, claiming he can see the “venom in the eyes” of one of the lawyers, Christopher P. Ruiz.

“It’s the defense of the desperate: ‘Kill the lawyers,’ ” replies Ruiz, whose high-rise office is just a few blocks down Wilshire Boulevard from Kaufman & Broad’s corporate headquarters.

Sending a Message

E. Allen Tharpe III, a senior partner in the firm for which Ruiz works, said the homeowners have turned aside settlement offers because they are furious over the company’s previous behavior. “They want to send a message to the building industry that they can’t get away with this kind of behavior,” Tharpe said.

According to interviews and an extensive review of depositions and court records, here’s what went wrong in Riverside:

Although the homeowners charge that their houses are badly built throughout, central to their case are homes built with second-story overhangs, known as double cantilevers, at the rear and sides of the houses.

In late 1983 and early 1984, after they moved into their houses, it became clear to some of the homeowners that something was seriously wrong: the second-story bedrooms slanted, the bathtubs did not drain properly, the toilets tilted, and gaps had opened between walls and baseboards.

Officials Notified

The case came to the attention of top management at Kaufman & Broad in the spring of 1984 when Martin G. Roberts, then head of the firm’s Southern California operations, said he got a call from a homeowner whose tub did not drain properly.

Roberts said he became curious when he found similar complaints in the company files and asked Gary Clark, then director of operations, to explain.

Roberts testified that Clark ultimately acknowledged that he had changed the design of the homes by extending a single overhang at the rear of the houses to the sides as well, in effect turning a single-cantilever home into a double-cantilever design.

It was a change that Clark made in the field without the advice of an architect or engineer because it provided more room upstairs in order to help salespeople, who were “having a tough time selling that particular house because the rooms were too small,” Roberts said in a deposition.

Confirmed by Subcontractor

Meanwhile, Valdemar Montalvo, president of the framing company that did subcontracting work on some of the Riverside homes, confirmed that he added the second overhang without new plans or engineering at Clark’s request.

Concerned about the problem, Roberts testified that he told Karatz what he had learned and recommended that Clark be fired because of the design change, among other reasons. Clark did resign, but Karatz then hired him back over Roberts’ objections.

Karatz “did not feel we could fill Clark’s shoes and still maintain the number of closings (completed homes) that we had projected for the year,” Roberts testified. Roberts said he resigned shortly afterward.

Karatz denied Roberts’ assertions regarding Clark and maintained that Roberts himself was asked to leave the company rather than resigning on his own.

Points to Plans on File

Clark has testified that a bona fide set of plans was used to build the double-cantilever homes. And while Karatz admits framing errors were made on the homes, he refutes allegations that the overhangs were improvised and points to a set of double-cantilever plans on file with the federal Veterans Administration.

Veterans Administration construction analyst Ernest Mentas, now retired, signed a sworn statement last June that he did indeed sign such a set of plans in April, 1983, prior to construction of the double-cantilever homes.

Construction plans are submitted for approval to the Veterans Administration to provide a measure of protection for veterans applying for federal loans. For homes carrying a 10-year warranty--as did the Kaufman & Broad houses in Riverside County--the structures are inspected by federal officials only after completion.

Local inspectors from the cities of Riverside and Corona were responsible for ensuring that the homes met building code standards at various stages of construction, such as the pouring of foundations and framing.

Other Witnesses

But no such double-cantilever plans for the homes in question can be found on file in the building departments of Riverside or Corona, and other witnesses besides Roberts and Montalvo testified that no bona fide plans were used to build the overhang sections of the homes.

“Kaufman & Broad’s production schedules were such that there was no time to get the plans or calculations drawn up and submitted for approval,” said Lou Baxter, former general superintendent with the company. “Production went forward immediately.”

When homeowners began complaining that their floors were sagging, company service representatives were told to cover up the fact that the problems were caused by a structural defect, according to sworn statements.

Peter Sorenson, a director of customer service for Kaufman & Broad for seven months in 1984-85, said in a sworn statement this spring that company Vice President Frank Scardina “gave me the impression that he wanted me to lie about the problem and deny and cover up the fact that a problem existed.”

The Stucco Theory

Sorenson also said company officials misled homeowners by telling them that stucco applied to the outside of their homes would prevent further sagging of the cantilevered overhangs.

“The stucco theory was created to cover up the truth and hide the fact that the homes had a structural defect,” Sorenson said in a deposition. “In fact, both Lou Baxter and Frank Scardina told me that the application of the stucco made the double-cantilever problem worse. . . . When Frank Scardina told me about this ‘stucco theory,’ I thought it was a joke. We both laughed about it for some time.”

However, Baxter insisted in a sworn statement that he did indeed believe the application of stucco would prevent further sagging of the second-story overhang, while Scardina denied having any such conversation with Sorenson.

Angry homeowners in Riverside also maintain that their homes might not be flawed if public building inspectors had not been so chummy with Kaufman & Broad.

Riverside city inspector Dean C. Johnson, now retired, admitted in a sworn statement that he received gifts from Kaufman & Broad of at least 120 2-by-4s, 60 sheets of plywood sheathing, 20 to 30 gallons of paint, four window frames, plastic piping, a countertop, a garbage disposal and miscellaneous hardware. Johnson, who testified in exchange for a promise that he would not be sued, said the company gave him and other inspectors liquor as well.

Inflating the Price

A sworn statement by former company tract superintendent John Davis maintains that Clark arranged for a subcontractor to pour a cement slab for Johnson’s mobile home and to hide the cost of the slab by inflating the price of other work billed to Kaufman & Broad.

“In order to bury the costs for this labor and material,” said Davis, “Gary Clark told me to tell the subcontractor . . . to overbill Kaufman & Broad for . . . work which was actually done.” Johnson denied in a sworn statement that the gifts were bribes, but he nevertheless admitted routinely falsifying inspections of Kaufman & Broad homes at the request of company construction superintendents.

Johnson said he frequently declared on official city reports that houses had been properly finished when in fact they were incomplete. He also stated that in many cases he signed final inspection reports for houses he looked at only from the curb or not at all.

Sometimes Johnson would not even require the company to obtain city building permits for houses until after foundations were poured and framing was to begin, according to a document in the suit.

50% Lapse Admitted

Davis said in his sworn statement that “Johnson on occasion would allow certain aspects of the beginning phases of construction to move forward without a building permit in order that Kaufman & Broad’s production schedule would not be held up.”

In a sworn statement, Johnson admitted that in 50% of the homes in the Kaufman & Broad tracts, he did not make legally required inspections of framing, insulation, exterior lath and wallboards, rough or final electrical wiring, rough or final plumbing and other elements of construction.

Kaufman & Broad denies giving presents to inspectors in Riverside County or improper relationships with the officials, pointing to an official company policy against making such gifts.

In the meantime, the Riverside County district attorney’s staff is reading through the volumes of sworn testimony in the case. “It’s something we’re still interested in,” said Assistant Dist. Atty. Randy Tagami.

Staff writer Ronald B. Taylor and researcher Tracy Shryer contributed to this story.

HISTORY OF PROBLEMS Problems involving Kaufman & Broad housing construction have brought accusations ranging from bribery to substandard construction, in cases dating back almost two decades. YEAR PLACE ALLEGATIONS ACTION YEAR 1972 PLACE Chicago ALLEGATIONS Former president of Kaufman & Broad of Illinois indicted for bribing a federal building official with $800 and three cases of liquor while head of the company. ACTION Former president pleads guilty to offering liquor as bribe and building official pleads guilty to accepting bribe. YEAR 1973 PLACE Chicago ALLEGATIONS Bribery, tax fraud ACTION K&B; fined $50,000 after pleading no contest to charges that firm was involved in bribing officials in suburban Hoffman Estates to obtain zoning change. Firm also pleaded guilty to filing false income tax returns. Six suburban officials and K&B; attorney also convicted. YEAR 1979 PLACE Chicago ALLEGATIONS Federal Trade Commission accuses K&B; of shoddy and deceptive building practices, including false advertising and poor-quality construction. According to one accusation, firm put undersized beds in model homes to make rooms appear larger. ACTION Without admitting guilt, K&B; signs agreement promising to stop such practices. Firms also agrees to fix or buy back defective homes built between 1972 and 1979. YEAR 1980 PLACE Milpitas, Calif. ALLEGATIONS K&B; construction supervisor and two city building inspectors charged with falsifying inspection reports. According to court records, one inspector received liquor and building materials as gifts from company. Records also show that K&B; routinely offered cases of liquor to city, county and utility officials in Northern California. ACTION K&B; found guilty and fined more than $200,000; K&B; construction supervisor found guilty and fined $5,000 and sentenced to 30 days in jail. City inspectors fined and placed on probation. YEAR 1984 PLACE Novato, Calif. ALLEGATIONS Homeowners’ lawsuit in 88-unit townhouse development details more than 40 different types of defects. Among them: Houses leak during heavy rains and roofs sag visibly. ACTION K&B; denies allegations and civil suit pending. YEAR 1985-89 PLACE Riverside County, Calif. ALLEGATIONS Owners of 54 homes file suits claiming defects, including sagging second-story floors, leaky pipes, cracked walls and other structural defects. Homeowners’ charges include allegations that houses built without bona fide plans and building inspectors were paid off by K&B; with liquor and other gifts. ACTION Sixteen homeowners settled out of court; other cases still pending. K&B; charges some homeowners with attempting to enrich themselves by suing. YEAR 1986 PLACE Fontana, Calif. ALLEGATIONS Dissatisfied homeowners appeal to City Council, contending that K&B; ignores their complaints of defects in homes. ACTION Fontana City Council votes temporary halt on building permits to K&B; until company fixes problems in homes. Dispute settled without lawsuit. YEAR 1986-88 PLACE Pittsburg, Calif. ALLEGATIONS More than 100 homeowners file suits charging defective foundations, cracking walls and other structural problems. ACTION K&B; denies allegations. Lawsuits pending. YEAR 1987 PLACE Canyon Country, Calif. ALLEGATIONS Extensive interior damage to 79 homes because of water leaks from substandard pipe. ACTION Lawsuits settled after homeowners picket a new K&B; tract and company spends more than $2.5 million to replace pipe and pay for water damage. YEAR 1988 PLACE Antioch, Calif. ALLEGATIONS City Council is deluged with homeowner complaints of cracked foundations and related problems. Said City Councilman Frank L. Stone: “We had an awful lot of residents from Kaufman & Broad developments coming to us saying that they felt they had been sold an inferior product.” ACTION City Council doubles number of building inspectors assigned to new K&B; housing tract and requires company to obtain reports of two soil engineers rather than one, as normally required.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.