Freeway Feared as Scar on History : Foes March Along Contested Route in South Pasadena

Within earshot of where state transportation officials want eight lanes of Long Beach Freeway traffic to wind through South Pasadena, preservationists and city officials on Sunday hoisted a white flag with blue letters bearing the message: “South Pasadena: One of America’s Most Endangered Places.”

While hundreds of onlookers sang along as the South Pasadena High School band played the national anthem, representatives of the National Trust for Historic Preservation presented the flag to symbolize the group’s recent designation of the San Gabriel Valley city as one of 11 endangered historic places nationwide.

“Any benefits derived by this (freeway) link cannot outweigh the devastation,” Wayne Ratkovich, a board member of the Washington-based preservation group, told the rally.

“It’s the land of the free, not of the freeway,” added William Delvac of the California Preservation Foundation.

State Sen. Art Torres (D-Los Angeles) told the cheering crowd: “We are going to stop this freeway.”

In combination with a pre-rally march along the proposed freeway route and a tour of architecturally significant houses that would be lost to the project, Sunday’s rally, organizers said, represented a new high water mark in the decades-long battle over a 6.2-mile gap in the Long Beach Freeway.

About 300 people marched the proposed route, the so-called Meridian Variation, advocated by Caltrans officials as the way to link the Long Beach Freeway with the San Bernardino, Pasadena and Foothill freeways.

Transportation planners consider the gap in the Long Beach Freeway as the last link in the Los Angeles freeway system.

A white Saab convertible carrying former and current South Pasadena officials and a mariachi band from El Sereno, surrounded by pom-pom waving cheerleaders of El Sereno Junior High School, embodied the spirit of the 2-mile march. The parade of boys on bikes, babies in strollers and people carrying placards went from the working-class streets of Los Angeles’ El Sereno neighborhood into more affluent South Pasadena, home to 24,000 residents.

Federal Highway Administration officials in recent months have been studying an environmental report on the Meridian Variation. Critics say completion of the project could destroy 7,000 trees and 1,500 houses, and force the relocation of 6,000 people in Pasadena, South Pasadena, and El Sereno.

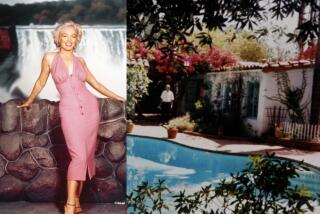

Among the houses affected would be 52 historic Craftsman and Mediterranean-revival houses, including the 1887 Queen Anne-style house, Wynyate, home of South Pasadena’s first mayor.

Five hundred people paid $7 each to tour 10 of the houses in Pasadena and South Pasadena.

At one, a home designed by Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey, who also planned the Rose Bowl and the Beverly Hills Hotel, people sighed over the prospects that the 1905 structure would be destroyed.

“It would be a crime,” said Sharon Thompson of Glassell Park. “Surely, there must be a better way.”

Opponents have proposed mass transit, including light-rail cars, or traffic-light synchronization as options to the freeway, which planners say would cost $450 million, but critics claim would require more than twice that.

A report on the reaction by federal officials to the state’s suggested route has been expected for weeks and, according to a spokesman, Caltrans hopes to submit it for review to the state Transportation Commission soon.

But freeway opponents have been lobbying heavily, including meetings last Wednesday with the chief legal counsel of the Federal Highway Administration who, opponents say, they persuaded to come from Washington for a first-hand look.

In addition, campaigns to forestall the project are being waged by a North Hollywood public relations firm hired by South Pasadena and the city’s San Francisco lawyer, Antonio Cosby-Rossmann, who has been prominent in environmental battles--including his recent work in behalf of Inyo County and its fight with the city of Los Angeles over water rights.

So far, the only legal action over the freeway issue came in 1973, when a federal court injunction required an environmental impact report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.