Brief Encounter With London’s Theater Delights

Examining the options in London’s West End theater district during a too-brief visit is like looking in the window of a toy store with your allowance already spent. The choices are beguiling and frustrating.

The Sunday Times last weekend remarked on the number of stars performing here. The list includes Peter O’Toole, Albert Finney, Janet Suzman, Anthony Newley (in a revival of “Stop the World I Want to Get Off”), Paul Scofield and Alec McCowen (the two of them in a Jeffrey Archer play that was unenthusiastically received by the critics).

Visible as well are Leo McKern (dear old Rumpole), Denholm Elliott, Nigel Hawthorne (familiar in the United States from the “Yes, Minister” television series) and Jane Lapotaire, Julie Walters (from “Educating Rita”) with Brian Cox in Terence McNally’s “Frankie and Johnny,” and Dame Judi Dench, one of Britain’s best stage actresses, in a much-praised revival, just opened, of “The Cherry Orchard.”

Should none of this please, there is always Agatha Christie’s “The Mousetrap,” now in its 37th year and 15,000 performances later.

At that the hottest ticket in town is evidently still “Miss Saigon,” the Vietnam War musical by Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schonberg, who also did “Les Miserables.” It stars Jonathan Pryce (from “Brazil”) and newcomer Lea Salonga.

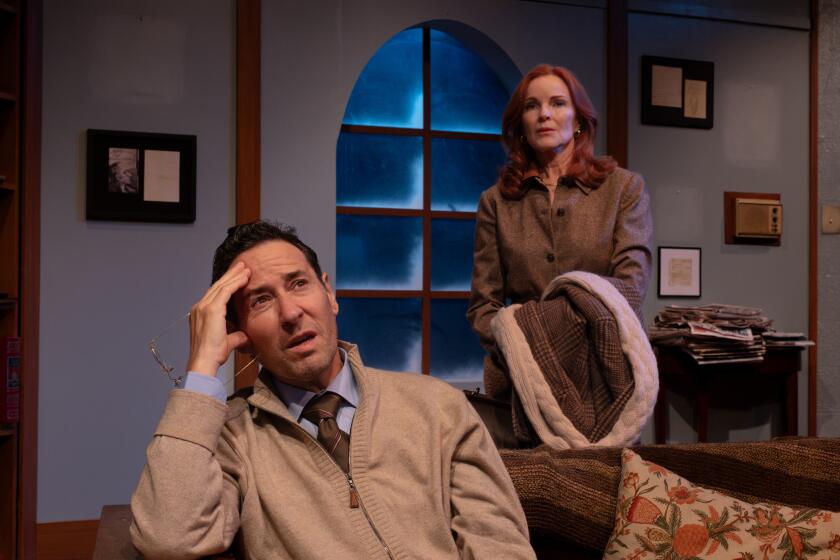

Nigel Hawthorne is playing the late medievalist and Christian philosopher C. S. Lewis (“The Screwtape Letters,” “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe”) in William Nicholson’s play “Shadowlands,” first done on television with Claire Bloom and Josh Ackland. It is based on Lewis’ marriage, when he was in his mid-50s, a confirmed and even misogynistic bachelor, to Joy Davidman, an American poet with whom he had had a long correspondence. She is played by Jane Lapotaire, who won a Tony for “Piaf.”

Davidman, ill with cancer when they married, went into remission and they knew great happiness until the disease struck again. His anguish over her last months and her death forced Lewis to confront again his previously-held serene Christian views about death. It is indeed a love story, and text and performances received generally rapturous reviews.

Channel 4 tapes an exit poll of critics at first nights, and one of the critics remarked, coming out of “Shadowlands,” about “the extraordinary sound of 1,400 people sniffling.”

Peter O’Toole is cavorting in “Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell,” a Keith Waterhouse play based on the life and writings of Bernard, a raffish chronicler of lowlife and much else, who is quite alive and as well as he allows himself to be. Ned Sherrin, the principal creator of “That Was the Week That Was,” has directed this unusual homage, if that’s the word, to a living writer.

Finney is starring in “Another Time,” a remarkably constructed play by Ronald Harwood, who earlier wrote “The Dresser,” inspired by his time as dresser to the late actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit. (A production of “The Dresser” opens Friday at the Palisades Theatre in Pacific Palisades.)

The first act of “Another Time” takes place in Cape Town, South Africa, in the ‘50s. Finney, partly paralyzed by a mysterious but as it turns out not imaginary ailment, cadges cigarettes off his son (Christien Anholt), a promising pianist, and argues in a fine stentorian way with his brother-in-law (David de Keyser), a professor of moral philosophy.

In the adjoining bedroom Finney’s shrewish and unhappy wife (Suzman) natters with her spinster librarian sister (Sara Kestelman). There are occasional interchanges through the door between the two rooms.

The stage revolves and the same scene is repeated, but this time we hear the women’s talk, with occasional interjections from the men (which we’ve heard before).

In Act II, the scene is London 35 years later. Finney is now playing the son, who has become a concert pianist with a world reputation. Young Anholt now plays the pianist’s estranged son. Mother (Suzman), aunt and uncle are visiting from Cape Town, which Finney left to continue his studies and has stayed away from since. (Playwright Harwood is also from Cape Town and has been long resident in London.)

The setting is a recording studio where Finney is doing some Rachmaninoff preludes. The turning stage alternately gives us the recording floor and the control booth, the two areas only momentarily audible to each other through the microphones.

Never, possibly, was an essentially serious play quite so funny. Never, possibly, was a Jewish family played in such an ethnically neutral way, lest the one-liners, of which there are some, seem only to be calculated comedy and the family less universal than it is clearly intended to be.

In the end, the play is about the persistence of the past: a difficult father remembered, the lacerating wars of father and mother remembered even more painfully. Not least, it is about South Africa.

In a time when fictions about South Africa tend to be hard-line and didactic, “Another Time” quietly (and inconclusively) poses the anguish of the white liberal, torn between making a gesture against apartheid and damaging or depriving those who are already apartheid’s victims.

Finney’s performance is large but also subtle and intense and becomes part of an ensemble, not a star turn.

Along the way Sara Kestelman as the spinster sister delivers a Harwood speech (two, actually) about the consoling, uplifting, nourishing, satisfying powers of literature that should hang framed in every library on earth.

Talking to Robert Hewison of the Sunday Times, Finney agreed that stars may produce commercial success, as they seem to be doing at the moment, but could also lead to timidity in the producers’ choice of vehicles, a surfeit of musicals and revivals.

But playwright Harwood tells me that “Another Time” is off to a bigger start than “The Dresser,” even though it is in its essence a more serious play. “And about South Africa at that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.