Seeing Black Dance in a Universal Context

“America’s a racist country,” says Texas-born choreographer and arts administrator Halifu Osumare. But in the coming epoch, she says, the nation will finally begin to live up to its own principles of cultural diversity--”to put up or shut up.”

Northern California resident Osumare, 43, is director of Expansion Arts Services and executive producer of “Black Choreographers Moving Toward the 21st Century,” a festival that opens its weeklong Los Angeles run today after a two-week stand in San Francisco.

In addition to symposia, lectures and master classes, the Los Angeles portion of the two-city event will feature a series of performances at the Wadsworth Theater in Westwood from Thursday to Nov. 19, presenting such artists as former Los Angeles Ballet soloist Christopher Boatwright and former Los Angeles residents L. Martina Young and Donald Byrd.

Lula Washington of L.A. Contemporary Dance Theatre, Bill T. Jones, Urban Bush Women, Spotted Leopard Dance Company, Dimensions Dance Theatre and Lines Dance Company will also perform. All of the companies scheduled for the festival have previously appeared in Southern California.

Osumare, who had the predominant hand in choosing both the performers and the panelists, sees the festival as helping to steer away from what she calls this country’s Eurocentric bias. “We have to re-think our history,” she says, “because our history was written by people whose visions were colored by their own upbringing and their own knowledge.”

“America has always had this vision of itself,” she adds, referring to the country’s pride in its melting-pot heritage, “but it’s been pretty hypocritical about it.”

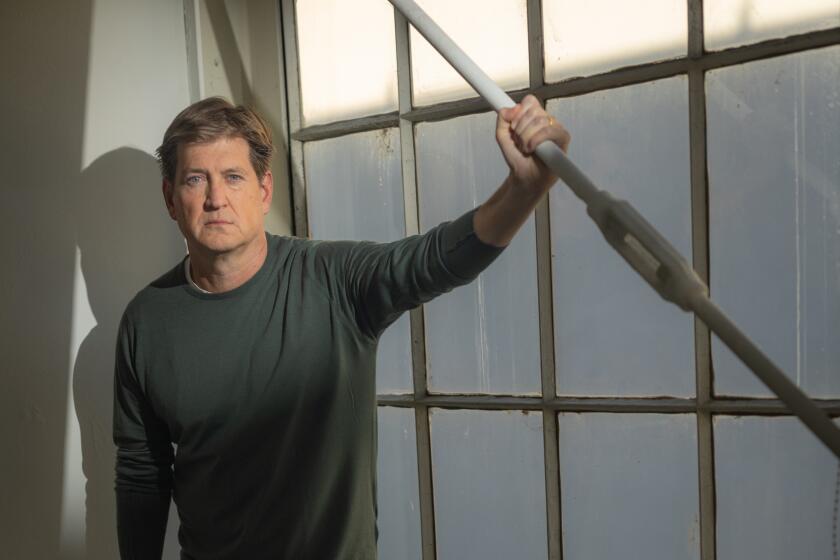

The tall, soft-spoken Osumare strikes the casual observer as neither a rabble-rouser nor a harried producer whose first major festival has just become a reality. Her pronouncements come in an easy, conversational tone and her eyes are just as likely to convey flashes of humor as of indignation.

She makes the point that audiences and critics are apt to accept blacks doing African dance. “But doing contemporary or postmodern work, they get affected by the nuance of racism. That’s why we are putting together the new and way out--the experimental--for this festival.”

The problem, she points out, is not limited to blacks. “Asians and Hispanics are faced with the same thing of dealing with contemporary dance and wanting their work to be seen as universal rather than being defined as ethnic.” According to Osumare, labeling works based on the creator’s race amounts to “ghettoizing the artist.”

“Why,” she asks, “should Dance Theatre of Harlem be described as a ‘black dance company?’ Is it just because it has a black artistic director and choreographer, or because of the number of black dancers in the company? It is just a dance company doing ballet.” Works by Jewish choreographers are not similarly labeled “Jewish dance,” she points out.

One of the goals Osumare and her colleagues have set for the talks and discussions that are part of the festival is some clarification of the term “black dance.” She says there is not a similar confusion around the words black choreographers used in the title of the event itself.

“None of these choreographers denies (being) black,” she explains, “but we have never said that what they are doing is black dance.”

Los Angeles attorney, arts advocate and founder of First Impressions Performances, Neil Barclay, producer of the Los Angeles division of the festival, says the purely ethnic evaluations are no longer valid when artists live in multicultural communities.

“Every artist--black, Jewish, Asian, Hispanic, Italian--has a tradition to build on,” he points out, “but in the ‘90s, the traditions will no longer resemble the originals. In the future, all these traditions will influence each other.”

The question of changing cultural focus will be the subject of a panel discussion, “The Future: Will the Black Choreographer Always Be Black?” at the California Afro-American Museum on Nov. 19. Barclay expects that issue to be the “most provocative theme” confronted in the course of the festival.

He sees one of the festival’s goals as “expanding peoples’ minds” and says that will happen through the performances as well as the discussions. “We want not only the black community, but a generic mix of audiences to see and celebrate these artists.”

Documentation of the diverse facets of the festival is also important to the producers. “That’s my academic side,” says Osumare, who is currently on the dance faculty at Stanford University, “I want to see something on paper from this and see it distributed around the country.”

“We want to document the process as well,” Barclay adds, “to show all kinds of presenters and tell them, ‘This is what you can do if you care enough to do it.’ ”

The festival will have a total cost of almost $250,000, according to Osumare. “Around 60% goes to the artists and to production,” she estimates. “The rest is between marketing, transportation and documentation and administration.”

Funding for the project came nationally from the National Endowment for the Arts, Rockefeller Foundation and Phillip Morris Co.; statewide from the California Arts Council; and on the local level from the Hotel Tax Fund in San Francisco and the City Cultural Affairs Department and UCLA in Los Angeles.

Although Osumare, as well as Barclay, would like to see similar festivals take place in other parts of the country, she advises prospective producers to “think twice. So much homework has to be done.”

“You may have a dream, but if you don’t have a track record in the field of arts administration and you don’t have the contacts . . . it won’t work!”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.